Milton Keynes, arguably the UK’s most successful new town has much to teach us about creating new places. Former sceptic Biljana Savic AoU explains what a place created 50 years ago can teach us about 21st century urbanism.

I have to admit that, for a long time, I’ve been a Milton Keynes sceptic – the low density, semi-rural feel of the city, its fast traffic and roundabouts galore, coupled with the almost universal absence of people from its public spaces never appealed to me. This is the only place outside the US where I was stopped by a local who saw me walking down the street in the city centre and, concerned for my safety, offered me a lift to the hotel that was no more than five minutes’ walk away. Unlike most of the other cities I visited, I could not find my way around MK without constantly consulting street signs, even though on paper the city plan looked stupendously simple. The urbanism norms found in other UK cities do not apply here.

But the undeniable truth is that MK is the biggest and most successful UK new town, that the people who live there like it and that it continues to thrive in economic and social terms, even during the prolonged recession and with budget squeezes all around. It is a place people choose to move to, a place where an admirable array of international and national organisations and businesses have their headquarters, and where two universities continue to grow, even though Oxford, Cambridge and London are very close.

Over the last decade or so I’ve had the chance to work with MK-based urbanists, from city officials to local communities, many of whom involved in its formation and long-term residents. More recently I’ve learnt more about it while developing the programme for The Academy of Urbanism’s symposium which took place in June this year as part of the first MK CityFest, marking the city’s 50th anniversary and exploring the urbanism of its past, present and future. Listening to the presentations and walking around MK during the CityFest, I started appreciating not just what has been achieved, but more importantly what we can learn from its successes and failures. Here are my 10 lessons from MK for all urbanists, especially those involved in creating new places. All views expressed here are strictly my own.

1. Have at least one great idea to start with – to sell the story, to inspire and attract pioneers

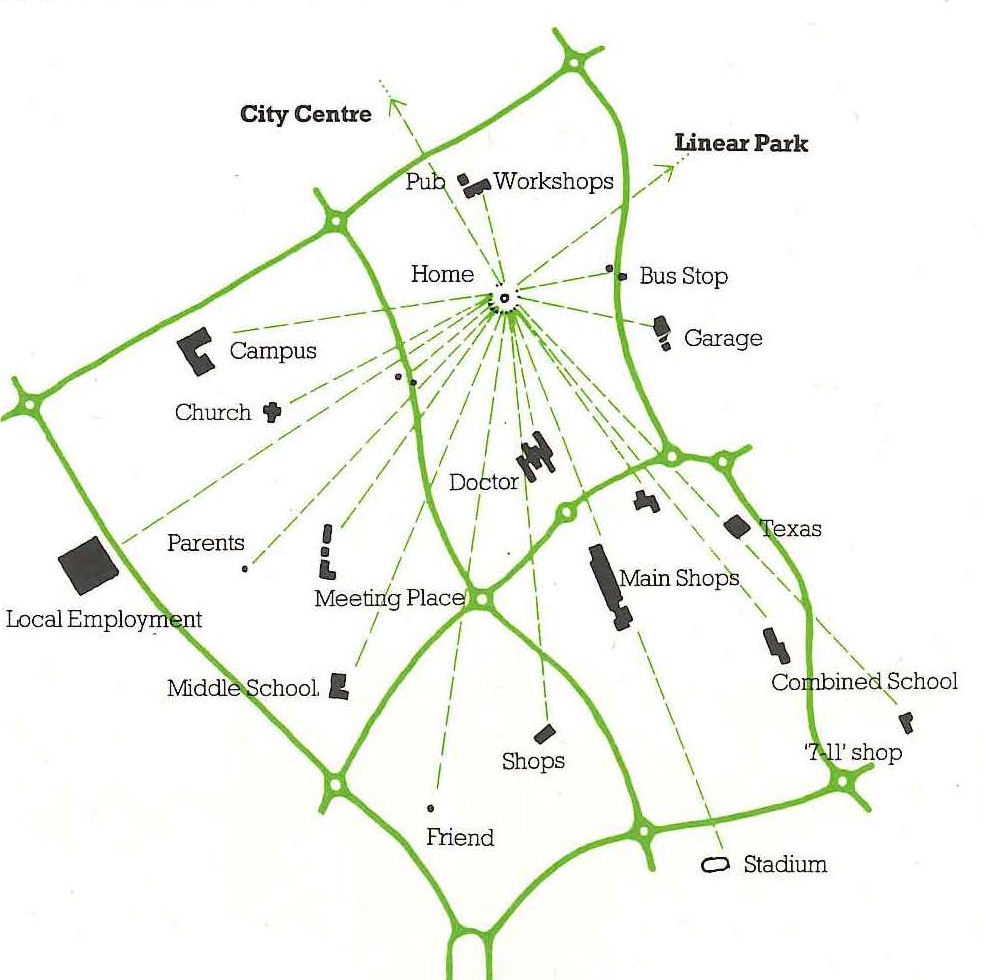

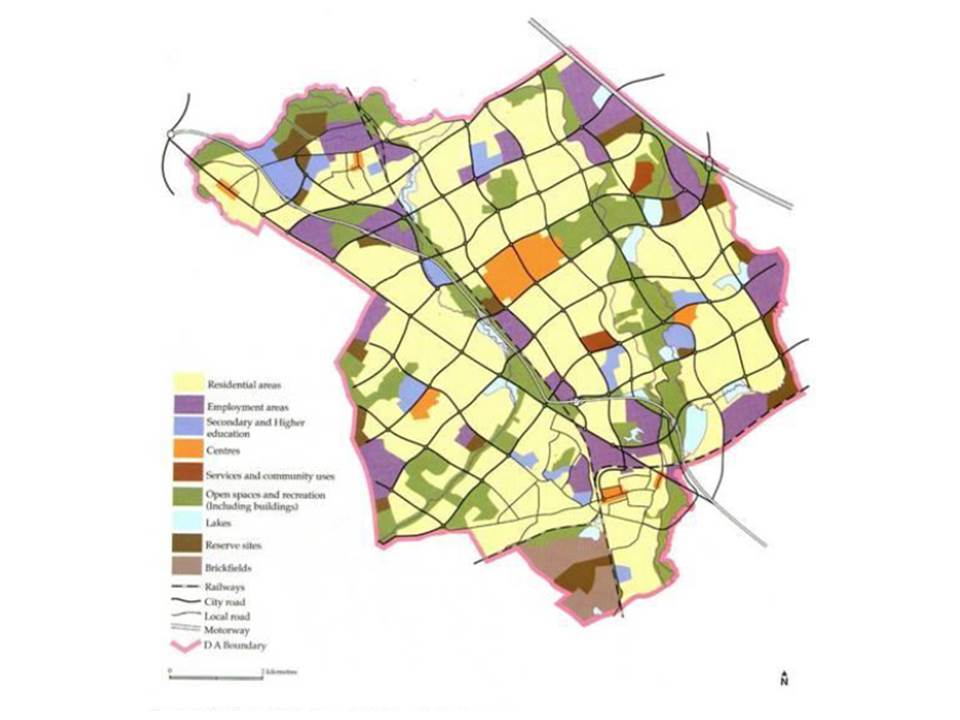

In MK the initial ideas of a two-layered urban grid, providing equal and easy access to all parts of the city, combined with a system of all pervasive green spaces, as well as largely low density residential neighbourhoods, each with access to a range of community facilities, appealed to those seeking a different lifestyle and a different kind of place. Good job opportunities locally and connections to the wider job market, a variety of neighbourhood and accommodation types, styles and affordability levels attracted a diverse range of new settlers – from affluent, highly skilled workers to those on modest or no income; from fledgling businesses to large international ones. They came and they largely stayed.

2. But make sure that great ideas do not get lost in the process – small changes often have massive unintended consequences

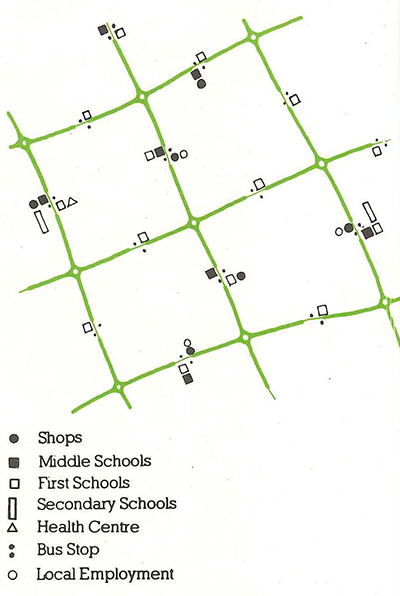

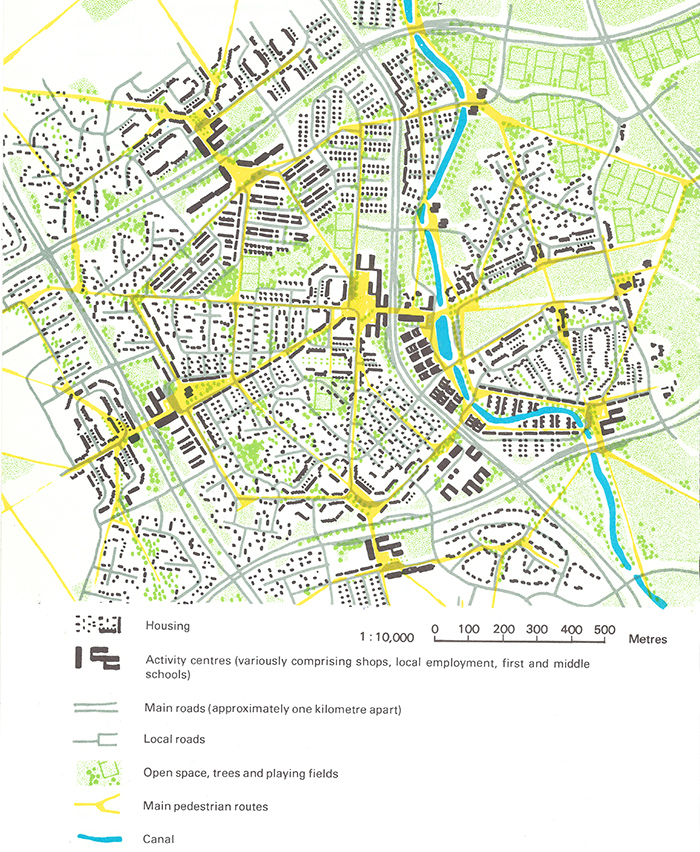

During the various design and implementation stages, some of the MK masterplan’s key elements were ignored or interpreted in ways that were not originally intended – the signalised cross junctions of the grid roads became roundabouts, resulting in higher speed of traffic throughout the city; the continuity of the secondary, local road network was lost in places; local ‘activity centres’ moved away from the intersections of local and main grid roads to the interior of grid squares; the green areas separating residential neighbourhoods from grid roads got bigger. The idea of equal access for all ended up being the reality of easy access for cars only. The green buffers along grid roads ended up dividing neighbourhoods and making cycling and walking routes unsafe. The neighbourhood centres that were supposed to be places of interaction and transaction turned into localised service hubs that declined over time. The city has had to live with these consequences of design decisions ever since.

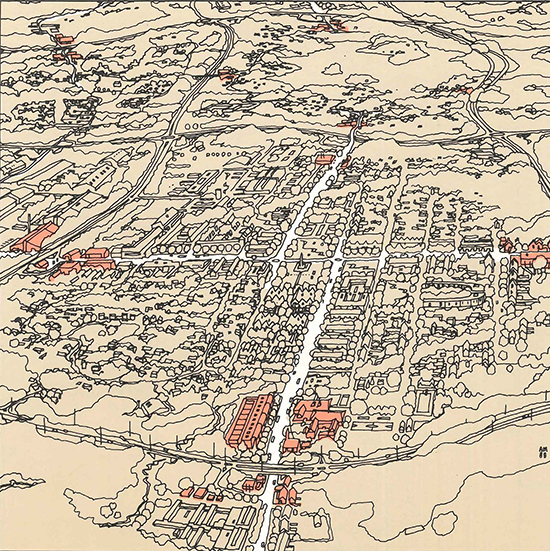

3. No place is a blank canvas – there is always a lot of existing place in any new place. Embrace it, work with it

MK is heralded as a new town, yet it amalgamated the old towns of Wolverton and Bletchley, and a number of medieval villages. These places remain vibrant and diverse, with a lot of local character and strong communities. They added a special twist to the new town. Also, the original rigid geometry of the grid was changed during the master planning process to reflect the undulating landscape and topography of the fields the city was built on – the resulting ‘wavy’ grid ended up being uniquely MK. The linear parks included in the original master plan turned the constraints of two river systems and flood plain issues into positives and served as the lungs of the city. MK’s success is so wedded to its unique position in the geographical centre of the country, half way between London and the North, and surrounded by the major cities in the Midlands. There could be no other place like MK anywhere else, all due to what was there before the first brick was laid down.

Facilities as planned

Facilities as built (1979)

4. It’s the grid, stupid – flexible, connected and open-ended urban structure is key to a good place

The MK’s relatively simple, open-ended primary grid allowed future city extensions and experimentation within grid squares. Indeed, urban solutions of different ages and developments of different architectural styles can be found in MK, but the primary grid provides an overarching framework within which these variations are possible without affecting the integrity of the whole. The original master plan provided plenty of capacity for growth within the primary grid structure for decades – it is more recently that the city started reaching the grid’s edges and an exploration of different urban extension models began. Regrettably in one of the recent extensions the grid’s simple but effective logic was ignored and future direct extensions of grid roads made impossible. Protecting the clarity and flexibility of the grid is crucial for the future of MK – it is the element of the city’s urban fabric that will outlast all others.

Activity centres as envisaged by original masterplan – reinforcing connections across grid roads

5. Quality pays, build it to last – and let it shine

MK’s public realm, with well-designed streetscape and landscape, executed in durable and high quality materials, is still one of its best aspects – another recognisable, uniquely MK characteristic. Likewise, some of the new town’s original buildings, such as the now listed main shopping centre, are of enduring quality which shines through, 50 years on, despite subsequent refurbishments. MK must retain this focus on high quality of its built environment and recognise it as an important factor in making it what it is – in the global race for businesses and people, it is the places that protect and value their environment that are the winners.

6. Don’t throw the baby out with the bath water – value what is unique

Even if only 50 years old, MK has already lost one of the great symbols of the early, bold period of its development – the futuristic Bletchley Swimming Pool. The city is now at risk of losing another one – The Point, the first multiplex cinema complex in the country. Its original bus station has been vacant for a while and the city has struggled to find a new use for it. A fascinating debate is unfolding on the heritage significance of the planned city and the strategic elements like the grid roads that simply do not fit into any comfortable listing or conservation process. With the gradual disappearance of, or question marks over the future of these city symbols – the firsts or the bests of their kind at the time they were built — there is a risk that some of MK’s unique character will go too. The future of these city symbols should not be decided solely on the basis of their often high maintenance costs or their inability to fit within established assessment methods, but the role they’ve played in the city’s genesis and continue to play in its narrative.

7. Keep experimenting and don’t be afraid of making mistakes – if you stop doing so, it will mean the death of the place

MK includes examples of some of the earliest environmentally savvy homes; it has been a testing ground for a range of approaches to neighbourhood and building design, including the more recent development of prefabricated, low-cost housing or current experimentation with smart city and new transport technologies. Hopefully this exploratory work will continue under the umbrella of MK Futures 2050 programme. And yes, some of the experiments failed, but others set the example for many others to follow. Pushing the boundaries of what is possible, testing new ideas while learning from the past, is a crucial part of place-making. More than anywhere else, new towns give us the opportunity to do so.

MK masterplan

8. Ambition, ambition, ambition – with high aspirations and people to carry them through everything is possible

The political and creative ambition, as well as courage to address difficult questions head on was critical in the early days of MK. This resulted in some innovative ideas in how to run the city and keep delivering the quality that was embedded in its early plans. The city’s expansion was only made possible through mechanisms such as the MK Tariff – a development levy introduced much before the national Community Infrastructure Levy mechanism. The model for maintaining the city’s vast green spaces and a range of community assets is through trusts set up by the MK Development Corporation. With a sufficient endowment they could not only carry the maintenance function but also keep growing the city’s assets without further recourse to public funds, which is truly unique and a great lesson to others. MK’s biggest challenge today is in keeping the level of ambition, keeping the bar high. Without that the novelty of this new town will eventually wear off and its growth might stop.

Proposals for planning the local environment are illustrated on this sketch which shows how a typical part of the city might be developed

9. The city-making work is never done – change is the only constant

In MK, just like in many other new towns there is a strong lobby of city pioneers — the first generation of ‘Milton Keyners’ – many of whom objecting to changes to the city structure and expansion plans driven by a combination of environmental, social and economic demands and concerns. This, for example, includes proposals based on higher development density, more integrated movement networks or a lower amount of green space compared to the ‘original’. MK is a result of a great initial effort and can be proud of what has been achieved — the constant stream of city delegations from all over the world, more recently from new towns in China, is testament to its success. But the moment it stops to respond to new trends and the ever changing, global and local socio-economic context will be its death.

10. It’s the people – great people make great places

Behind MK’s success are visionaries who were not afraid to stick their neck out and make bold decisions, including the urbanists, landscape designers and architects who worked on its early plans and literally laid out its streets in the fields. MK is a place of new comers, of mixing, or embracing new people and their ideas, these days a place where long-established communities exist alongside the transient and the more recently developed areas. At this point in its history the first generation of its residents is still around and very vocal, and the second and third generations are starting to find their own voice and to move the city forward. The city’s strength is in its social mix and in the continuous embracing of new people, from students, to immigrants, to global talent. MK’s future must be multi-generational and socially diverse, and in opening its arms to other cities, towns and communities around it.

Biljana Savic AoU is a director of The Academy of Urbanism

I love your analysis of MK. As one of the people in the original master plan team I share your pleasures and your regrets about the ‘small’ changes which made it so much less good than it should have been. Superb selection of images. Thanks. My version (2001) is at https://michaeledwards.org.uk/2007/02/03/what-went-wrong-at-milton-keynes ?