By David Porter

We are seriously misinformed about information. Everyone seems to agree that there is more information in the world than ever before. But is there more wisdom? Are we actually better informed about our world than people 40 (or 400) years ago?

Part of our problem is that we bundle very different things together under that single term – ‘information’. Compared with the world of food, for example, our vocabulary for talking about ‘information’ is, if you will forgive the pun, starved of helpful terms. With food we can talk of global food production, without confusing it with what is available to conveniently buy, and we don’t confuse that with what we can store locally in our fridge, and we don’t confuse that with what we can comfortably eat (and digest) in a meal. With ‘information’ the same word is used to describe global production; the available supply; the locally storable and the comfortably digestible.

With food we have a word for consuming it – ‘eating’ and although we have a word for consuming information –‘learning’, we tend to associate this with schools and colleges, not thinking of it as an essential activity of everyday life – we cannot think without learning. In many ways ‘digestion’ is a better word than ‘consumption’ for it describes the way something which was ‘out there’, becomes digested and ‘part of us’. We are not only what we eat but we are what we know. Learning is as essential a biological function as eating, breathing and sex. In all these cases something is transferred from the outside world to become part of us. More amateur biology – a lizard has eyes that are not so different to ours – a retina with many millions of receptor cells. Light falls on these cells and any difference in the pattern of light stimulates them, but the lizard does not ‘see’ these changes unless the pattern of change – of movement – can be recognised as representing prey. Then the lizard ‘sees’ and strikes with great speed. All the other shifting patterns of light that stimulate the retina are neither here nor there – it is only the patterns that specifically represent food that stimulate the lizard’s brain. It is the message ‘this could be grub’ that is information for the lizard. As Gregory Bateson put it: “information is news of difference that makes a difference.”

We are not so different from lizards for very little of the stimulus that activates our senses makes it into our conscious mind. As many of the acid-victims of the 1960s found, if you open the doors to perception too wide, you go crazy. To remain operational in the face of the huge influx of stimulus we use much of our huge brain capacity to filter out what is coming in and predict what will happen next – a double act that we invented long before we transferred it to ‘predictive texting’ and ‘spam filtering’ for our gadgets. It is a wonderful skill – intuition.

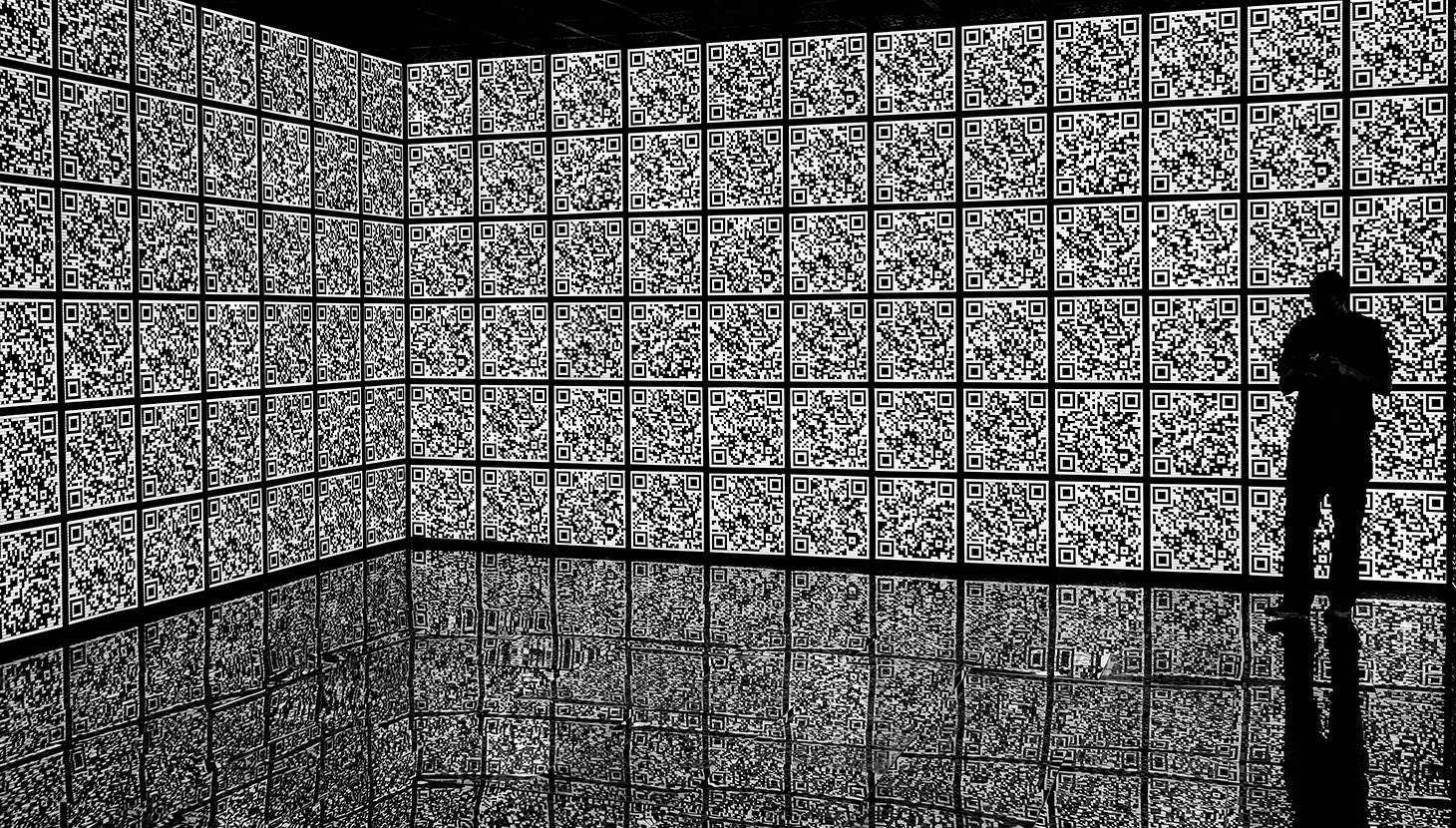

The thing about information is that it should inform so it changes, in a small way, our minds. My issue with ‘information’ is not its supply, which seems close to infinite, but its digestion which, as a biological function, has a lower and upper threshold – too little and we go hungry, to much and we blow-out and become inactive. Being bloated on ‘information’ is similarly uncomfortable. We are not in need of more information but better information – the learning equivalent of a varied, balanced and healthy diet. The balance is what intuition is for and I’ll return to next time.

David Porter AoU is Professor of Architecture at the Central Academy of Fine Art in Beijing