Latin America was colonised as a large system of interconnected cities and is now the most urbanised continent in the world with over 78% of the population living in cities. It also has the largest informal economy in the world with only 30% taxpayers. Creating a welfare system under these conditions to solve the housing shortage is challenging to say the least. The case studies presented here manage to do just that, but can they be replicated?

By Dr Claudia Murray AoU

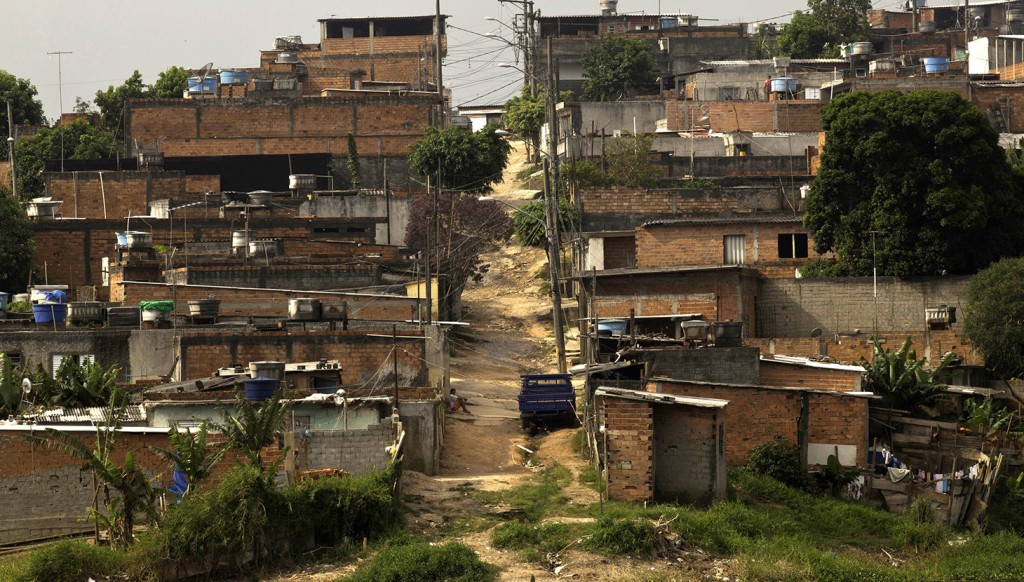

Housing deficit is a global problem, where the dearth of available living accommodation is often solved by informal means while creating hardship and health problems for much of the world’s poorest communities. According to UN-Habitat, 23.5% of Latin Americans live in slums and the region has a housing deficit of 50 million units. By comparison, slum dwellers in Asia amount to 60% of the total population, while in Northern Africa it stands at 13.3%. China is tackling its informal housing crisis by embarking on the largest social housing project in history with a target of 36 million housing units by the end of 2015.

Around the globe countries face increasing demographic changes such as rural to urban migration, longevity and the reduction of household size, all of which directly affect housing demand. On the supply side, lack of affordable land and government budget cuts further add to the financial constraints. In addition and in emerging markets, inefficient tax collection and the informal economy pose another barrier for the development of an efficient welfare system. According to the World Bank, 60% of Latin American workers are in the informal job market. The region also has the highest growth rate of remittances as a percentage of GDP, which stands at a staggering 133% compared to 89% in Emerging Europe and 72% in Emerging Asia. Finally, clientelism and elitism is another problem as most rich families manage to receive tax exemptions from government officials, meaning that value added tax is the main source of government income, hitting hardest the poorest sectors of the community.

Despite decades of military control and repression, Latin America is one of the most socially active when compared with other emerging markets. Community groups, NGOs and other forms of social activism have erupted after the transition to democracy, with countries like Brazil and Chile now held up as examples for their achievements in participatory budgeting and urban upgrading programmes. Not surprisingly, the headquarters of the World Social Forum is in Porto Alegre, Brazil. Paradoxically, these social approaches are emerging in parallel to a more neoliberal approach taken by some municipalities which are viewing the upgrading of informal developments not only as development opportunity for the private sector, but also as a means to legalise land titles and turn slums into taxable zones.

Among the various urban upgrading programmes spreading across Latin America, the two main approaches are a) developing new dwellings or b) delivering improvements to the area’s infrastructure. Both approaches depend on geographical conditions in each location, and decisions are taken according to environmental safety. Sometimes a mix of both approaches exists. The examples presented here illustrate the two possibilities: Quinta Monroy was an informal development whose settlers each received a new dwelling, while Cantinho do Céu has seen improvements to the area.

Quinta Monroy is located at the very heart of the city of Iquique, Chile. Informal development began there in the 1960s and by the year 2000 there were over 100 families living in precarious conditions in an area of around 5,000 sq. m. Being in the city centre means the land is theoretically higher in value, and therefore efforts were made to relocate those living there. After several attempts to move families to the edge of the city failed, the authorities decided instead to help the community legalise their settlement and strengthen their roots in the area, appointing the architectural firm Elemental to provide the community with a new housing development.

In 2003 Chile’s budget for social housing was very low – just US $7,500 per dwelling – to cover land acquisition, infrastructure as well as the construction of each house, and yet at the time land alone in the periphery of Iquique was worth around US $20 per sq. m. This presented Elemental with something of a financial challenge as well as a typological challenge in relation to social housing.

Their strategy for Quinta Monroy was effectively based on sweat equity: a reinforced concrete shell (walls, floors, roof and staircase) is provided, with all the necessary plumbing but minimal fittings. The families themselves then customise their units, adding appliances and furniture at their own expense. The system relies on the families to find the means to finish their houses. Their homes are therefore the materialisation of their earnings in the informal job market. The design team involved the inhabitants directly, seeking their views and preferences.

In Chile, this was an unprecedented approach to social housing: low income families are typically given little input and just have to accept and be grateful for what they are given. The urban design layout also included four open public piazzas. These spaces were left for the community to customise, such that every family could contribute to the character of the open space, even if this was only by virtue of how they decorated their own façades.

Cantinho do Céu

In Brazil some of the poorest urban favelas are found in São Paulo. The favela has been gradually and informally populated since the 1980s, but it was only in this century that the Municipality of São Paulo decided to take action and allocate funds for redeveloping one of the most deprived areas in the city.

One favela, Cantinho do Céu, lies on the left bank of the Billings dam, which is vital for the city of São Paulo, providing one third of its fresh water. It is also a nature reserve protected by the Brazilian government. Concerns over its potential contamination due to waste disposal in the dam by local inhabitants was a key imperative for the government to take action.

The Municipality commissioned Boldarini Arquitetura e Urbanismo to devise a scheme to provide a safer environment for residents and formalise the land titles of their properties. Developing social housing in the context of a nature reserve was a challenge, even more so because the area has suffered severe flooding in recent years. Most of the building works executed in Cantinho do Céu, such as sanitation, flood barriers and road paving, were also aimed at recovering and protecting the wildlife. So far, 11,000 families have benefited from the scheme and local wildlife is thriving once again.

The success of both these schemes has been widely publicised in Latin America, with both architectural firms winning awards and Quinta Monroy in particular featuring in an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. The problem that now arises is how to repeat the density of this development on a wider scale. The question of how to apply Elemental’s approach, for example, to one of the largest favelas of São Paulo, Paraisópolis, is populated with difficulties. In pursuit of higher density, Paraisópolis resembles European social housing blocks developed in the 1970s and 1980s. Indeed, it can be argued that Brazil has a legacy of modernist schemes and whilst Brazilians are quite familiar with life in tower blocks, their failings are just as apparent as their Europe counterparts.

But it is not just a question of scale in relation to form, the issue is also about scale in relation to process: Quinta Monroy deployed a taskforce of architects, social workers, engineers and a wide range of academic experts to work on solving the problem on behalf of just 100 families. In comparison the target group in Paraisópolis is 40,000 people, who would probably need to be decanted. In the process of building new units, the Municipality of São Paulo relocated people to temporary camps while bulldozing their current favela. The break in continuity raises the issue of whether a community can survive the shock.

The other unintended outcome of formalising settlements is that the inhabitants realise the worth of their new homes by turning landlord: there are media reports of people letting their flats who have themselves moved to a favela elsewhere. This tactic has prompted the government to change legislation and unusually only give property titles to women, since they are more likely to value better living conditions and remain with their children in the new units. This brings to mind the question of whether the community that once existed is still effectively intact, given how easily members seem to want to move away after receiving their new houses.

There have been other reports in the media that many new social housing schemes are developed in complete isolation, far from job opportunities and with little transport connectivity. Furthermore, lack of adequate design and poor technical advice are creating new problems, such as proposals to canalise local creeks, which could lead to an increase in summer flooding. Undoubtedly social participation is a step towards equality but technical supervision should be better provided.

In contrast, the intervention in Cantinho do Céu has had less impact on neighbouring areas, perhaps because the architects’ contribution was to manage what was already in place. Although some families were relocated, eviction due to flood risks could not be avoided; and whilst road access has been improved, there are still issues with connectivity as the main transport network of São Paulo does not reach an area that is used by over 10,000 people, but this problem will no doubt be addressed in future.

The bigger issue at stake in Latin America is now to address the endemic social inequality and lack of social mobility in urban areas. Even in a small community like Quinta Monroy and despite all efforts from architects and social workers, home owners insist on building fences and gates around their new neighbourhood. The need to demarcate their territory seems too strong to resist, but it has of course produced ghettoes in which social mobility is almost impossible.

No scheme will ever succeed if it is built as a ghetto from the outset, it will simply stand as a symbol of social failure. The ongoing sustainability of current government efforts to reduce informal developments is still uncertain, but what is clear is that current approaches require more conclusive research before governments and policymakers wade in and destroy existing communities and livelihoods.

Dr Claudia Murray AoU

Research Fellow, Henley Business School