Urbanism and Garden Cities are uneasy bedfellows. In a piece in The Guardian, Richard Rogers wrote ‘With intelligent design and planning, we don’t need to overflow into new towns on greenfield sites; doing so would damage the countryside and – more importantly – wreck our cities’. As winner of this year’s Wolfson Economics Prize, which called for proposals on how to deliver a visionary, popular and economically viable new Garden City, David Rudlin responds.

Urbanism and Garden Cities are uneasy bedfellows. In a piece in The Guardian, Richard Rogers wrote ‘With intelligent design and planning, we don’t need to overflow into new towns on greenfield sites; doing so would damage the countryside and – more importantly – wreck our cities’. As winner of this year’s Wolfson Economics Prize, which called for proposals on how to deliver a visionary, popular and economically viable new Garden City, David Rudlin responds.

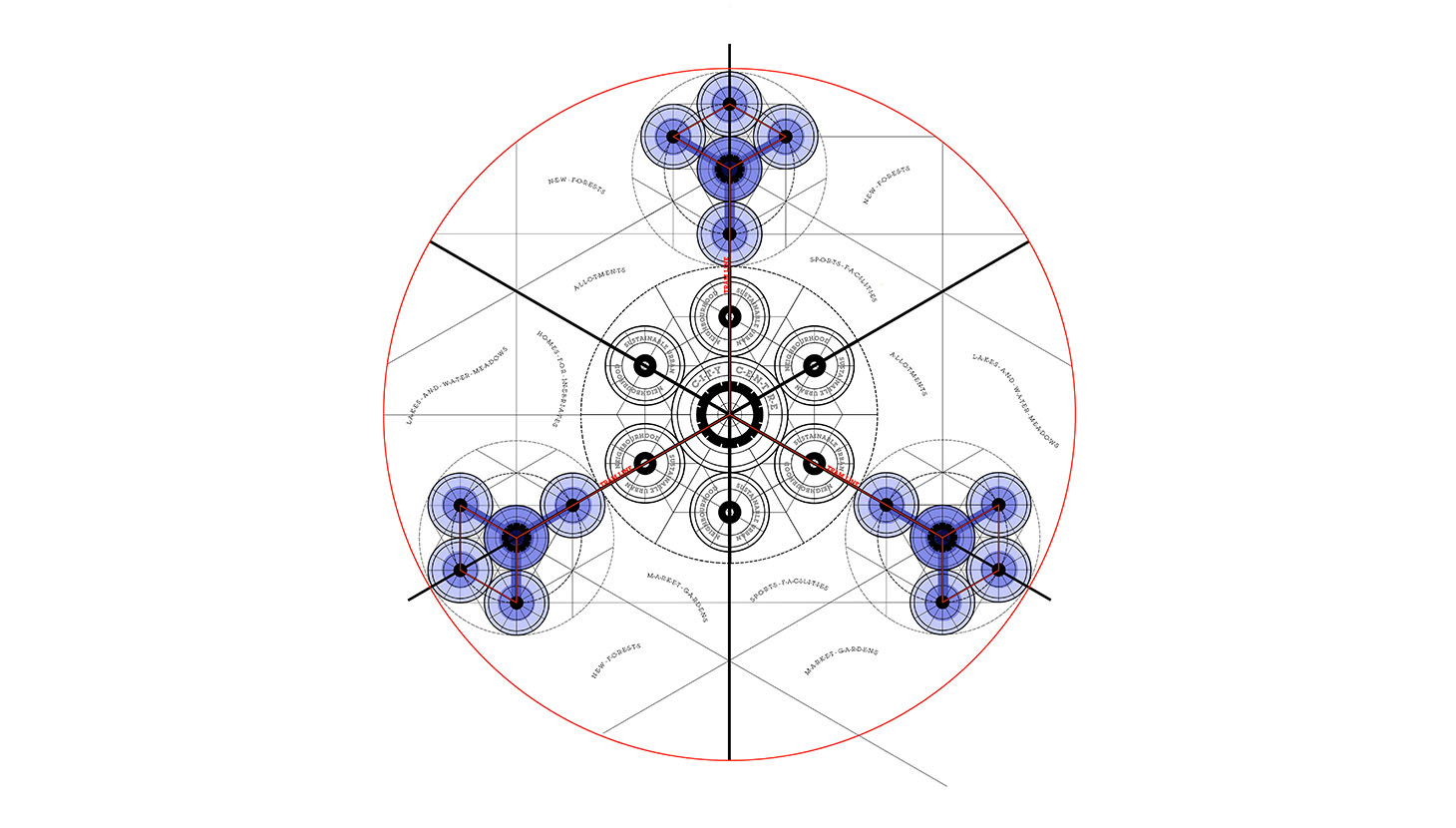

The Garden City is not much more than a hundred years old. It was the late 1890s when a parliamentary stenographer by the name of Mr. E. Howard coined the phrase in his book Tomorrow – a peaceful path to real reform. This was essentially a political pamphlet proposing reforms to the economic and social structure of society and was one of many Utopian tracts in circulation at the time that were prompted by concerns about the state of industrial cities. Howard’s contribution is the one that remains with us, partly because of some really good graphics, and partly because the Garden City is such an appealing brand.

In a poll of 6,000 people undertaken by Populous this year, 74% of those asked agreed that it is a good idea to build new garden cities to help meet Britain’s need for more housing. To all political parties seeking to build support for a major increase in housebuilding, the Garden City remains a powerful idea. The Wolfson Economics Prize, that commissioned the poll, was the latest attempt to do this. The prize asked three questions: what should be the vision for a Garden City? How can it win public support? And, how can it be viable without public subsidy?

At URBED, as elsewhere in the Academy, we debated whether we should submit an entry. Wasn’t the Garden City, at least in the form that it has been interpreted for much of the 20th century, the thing we are against? Wasn’t it the inspiration for new towns and suburbia that have sapped the energy out of urban areas, as Richard Rogers argues? The conclusion we came to was that these were the very reasons the Garden City should be of interest to urbanists.

In his Three Magnet diagram, Howard suggested that the town and the county both had good and bad points. The city, for example, might suffer from ‘foul air and murky skys’ but was also a place of opportunity and amusement with ‘well-lit streets and palatial edifices’. The country on the other hand might benefit from the ‘beauty of nature’, ‘fresh air’ and ‘low rents’, but it lacked ‘society’, ‘public spirit’ and ‘amusement’. As Howard said, ‘town and country must be married, and out of this joyous union will spring new hope, a new life, a new civilisation’.

Since then, opinion has been divided between those who believe that the Garden City combines the best of its ill-matched parents and those that think that it brings out their worst qualities. Proponents of the Garden City have come to see it, not as a way of reforming the city, but as an alternative to it. I spent much of the 1990s taking part in ill-tempered arguments where I was accused of advocating ‘town cramming’ and forcing people against their will to live in degraded cities. I, in turn, gave as good as I got, but I never quite managed the power of Jane Jacobs’ put-down when she described Howard’s aim as being “…the creation of self sufficient small towns, really very nice towns if you were docile and had no plans of your own and did not mind spending your life with others with no plans of their own.” 1

By the 2000s, with the advent of the Urban Task Force and the undeniable renaissance of many of our cities, a truce seemed to have broken-out between these factions. However, when I was invited to take part in a debate earlier this year on whether we should ‘loosen our green belts’ at the Heseltine Institute in Liverpool, I witnessed an outbreak in hostilities as virulent as ever and in which, on that particular evening at least, I seemed to be in the minority.

Our Wolfson essay is an attempt to bridge this divide. To say that we must continue to prioritise housebuilding within existing urban areas, but that this is not enough. In the late 1990s URBED produced a report for Friends of the Earth that argued that 75% of all new housing could be accommodated in urban areas. We called our report Tomorrow: a peaceful path to urban reform – which didn’t do a great deal for relations with the Garden City lobby. Nevertheless, by 2006 the country was indeed building three quarters of all new homes in urban areas. This figure peaked at 81% in 2008. This was the urban renaissance that we had advocated for so long and it came at the end of a decade when my hometown of Manchester saw a 20% increase in population.

However, there was a problem because throughout this time we had not been building enough homes. We need to build more than 200,000 homes a year and have only achieved this figure twice in recent years: once just before the 1990 recession and once just before the Credit Crunch. Furthermore half of the new homes built during these years were apartments and some of them were not very good. The housing that we had prevented from being built on greenfields was not transferred to brownfield sites, it just didn’t get built at all. Sure, there is more we can do to increase urban housing and continue the repopulation of our cities, but if we are to meet our housing target we also need to focus on the 25 to 40% of housing that will be build outside urban areas.

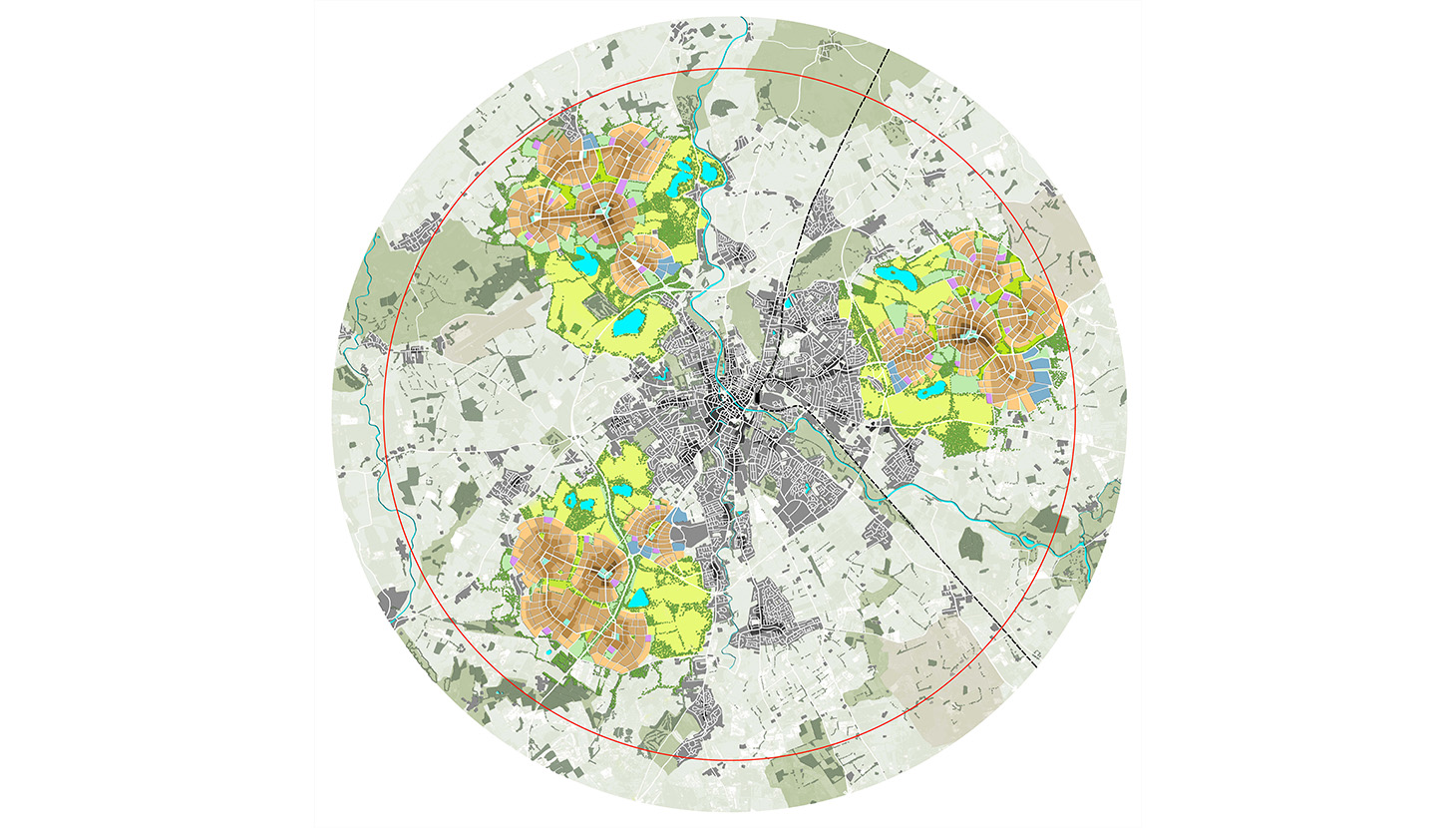

In our Wolfson submission we argue that we shouldn’t leave this to the volume housebuilders and we certainly shouldn’t build entirely new towns. It is impossible, we suggest, to build a new Garden City from scratch: there simply isn’t the value in the building of new homes in garden cities to fund the infrastructure needs for even a modest town, let along a city. Instead we suggest grafting Garden Cities onto the strong rootstock of existing cities.

In doing so we need to rediscover the spirit that built Edinburgh New Town or Bath or for that matter Newcastle’s Grainger Town or London’s Bloomsbury. None of these were built on brownfield land, they were built confidently on the fields that surrounded the city and in doing so enhanced its beauty and setting. These fields of course are today in the Greenbelt and are the most closely guarded of all the green fields. However if, as Urbanists, we are serious about meeting housing targets, we need to have the confidence to build on this sacred land and, in doing so, use the Garden City as a way of expanding the city rather than building an alternative to it.

David Rudlin AoU a director of The Academy of Urbanism as well as being a director of URBED and a Honorary Professor at Manchester University.

1 Quote taken from The Death and Life of Great American Cities by Jane Jacobs