A resilient city is one that allows change without losing its essence. Ombretta Romice and Sergio Porta AoU argue that resilience of cities lies in the relatively small urban components that can adapt, assemble and reassemble.

Recent data and predictions on the rate of urbanisation make cities the most common living environment of the future by far, with the current 3.8 billion inhabitants – which now make up for over half of the global population – set to increase to two-thirds by 2050. In its 2013 report Streets as Public Spaces and Drivers of Urban Prosperity1 UN Habitat predicts that over three-quarters of these new urbanites will locate in informal settlements, and the effectiveness of governments in building, developing and managing the homes of new and existing urbanites is set to decrease.

One could see the prospect of having less money and less control to deal with more pressures as a scary proposition – in fact, many do. Others may see it as an opportunity, following on from Jane Jacobs’ notorious lament for the malicious effects of “cataclysmic money”2 on cities, which necessarily and restrictively ties development to large scale decision-making, financing, coordination, and management, be this institutional or corporate. The subject is too great to take either position, but here we aim to show that the prospect is not doom and gloom and in fact, a lot is being done already and is available to embrace our urbanising future with a degree of optimism.

Much of it boils down to defining what is failure and what is success. Whilst interpretations depend on what profession and perspective we examine them from, we shall from now on focus on urbanism and cities, and relate success and failure to how our cities cope with change and transformations over time; change, and time, are consistent conditions across which cities develop. On the one hand, we are greatly affected, at local level, by global dynamics, from climate to markets fluctuations; on the other hand, we impact on the global level with the accumulation of local dynamics, to the point that a new geologic epoch, called Anthropocene, has been identified to describe the ‘great acceleration’ of human activity on the globe since the 1950s4.

The city’s relationship with change then, is fundamental because of the scale and pace at which this is now happening – through migration, immigration, alterations in life patterns and cycles, technology and the economy.

Resilience and form

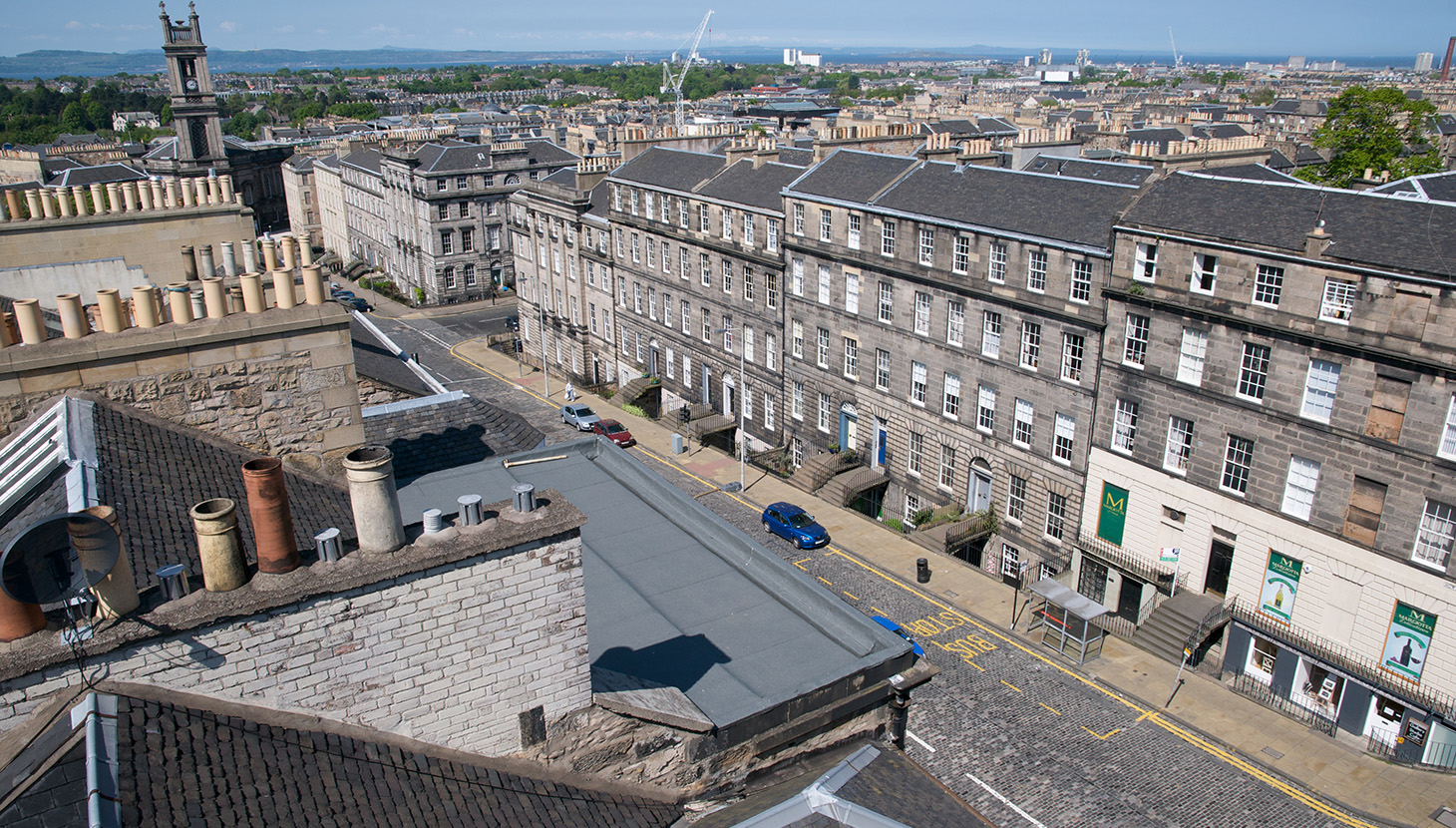

Resilience, as an essential property of places, is inherently linked with the prosperity of cities as the UN Habitat report notes. Places that are resilient show a high capacity to absorb change, to assimilate transitions, without having to renounce what gives them character and structure. Resilience can be considered at many scales in the environment. As our interest is in urban design, we shall think of resilience primarily in relation to city form. For too long the design professions have lived in a creationist mindset in which the designer’s task was to create the final product of the city, or what we can ultimately see, its form. Had we understood that cities are an evolutionary phenomenon, and that diversity does not come by design, we would have focused on the permanent and universal structure of cities to inform the process of change rather than trying to create and fix its final result from the start. There is no such thing as a final result, in cities as much as in life. As designers following an evolutionary approach, the structure is our focus. We should be interested in those components and their relationships, that survived through time, recurring across different scenarios. What remains through change, has resilience.

The form of resilience is made of relatively small components that can adapt, assemble and reassemble. It is a malleable urban tissue whose minimal unit of development can generate structures substantial enough to embed meanings for their users, be these individual, groups, or societies; structures complex enough to support modern life as an efficient, interconnected, multifunctional system; structures adaptable enough to withstand and react to change – be this significant or small, occasional, or recurrent; structures versatile enough to respond in different contextual and cultural manners to similar pressures.

Resilience then, depends on a system of units that maintain their own identity even when combined into greater wholes, and wholes that accrue their own character and identity whilst increasing, or changing, in complexity and functionality.

The plot as a reliable component of greater wholes

The plot, intended as the minimum unit of developable land, is a consistently recognisable feature of the built environment across time and as such, has attracted some consensus over the past years as a meaningful unit of development1 for the next generation of cities. The plot may or may not coincide with ownership subdivision. It is crucially important to distinguish the unit of development from the unit of ownership, as fine-grained development must – and can – be made compatible with large land ownership in processes of urban regeneration.

With a continuing trend towards single-use, suburban developments on large plots, we are in the process of losing the diverse, close-grain urban fabrics that once served as the foundation for our most beloved streets and flourishing town centres and which we still cherish and seek, as setting for both engaging, enhancing and practical ways of life. This has provoked urban designers and town planners, academics, community organisations and governments at all levels to rethink how to achieve more fine-grained, contextual, sustainable in time approaches to contemporary place-making, able to capture the everyday human experience of places. Based on the fundamental importance of the plot in urban development, Plot-based urbanism (PBU) is now emerging as a viable approach to place-making, aligned with the growing role of the self-build and the right-to-build agenda in the UK and Europe, in the new financial scenario, pursuing compact, sustainable urban design and masterplanning in an evolutionary perspective. Plot-based urbanism seeks to inform urban planning and design strategies in a way that is not only conducive to incremental growth and mixture of land uses and tenures, but is also resilient to economic risks, encourages informal participation, and respects local culture.

The quest for a new science of cities in the community of urban scholars is embracing the field of the science of complexity and, generally speaking, a more evidence-based approach to cities and the built environment. Plot-based urbanism is a practice of place-making that takes advantage of this new climate, first of all by looking at evidence of urban form structure, what it is and how it works. As such, Plot-based urbanism has developed a specific focus on urban morphology, a niche of urban studies that has for a long time struggled to find its way in mainstream urban planning and design and yet has been an integral part of the shift towards a more scientific, interdisciplinary and evolutionary understanding of cities which is now becoming more significant. Working across these two areas is helping urban design strengthen its conceptual, structural and methodological principles.

Plot-based urbanism and masterplanning for change

The Urban Design Studies Unit at the University of Strathclyde has invested almost 10 years of work to produce, catalogue and analyse some of this evidence, at all scales, with colleagues from a range of disciplines, clarifying the basis for a Plot-based urbanism approach to masterplanning and city design.

Recently, the first plot-based urbanism summit, an event organised by the Unit in October 2014, gathered together leading practitioners and policy makers, including UN-Habitat, to discuss the meanings and challenges as well as the practice and policy- making attributes of Plot-based urbanism. The team emerged from this event are all in some form committed to the advancement of Plot-based urbanism both in science and in practice. The Plot-based urbanism agenda is moving ahead, with Sheffield University having hosted the next event in April 2015, a further event planned for late 2015 in London, and a final event in spring 2016. Here the principles of Plot-based urbanism will be discussed and presented to a wider audience of professionals and academics, and the Urban Design Studies Unit will present its developing work on ‘masterplanning for change’.

Watch this space!

Dr Ombretta Romice is a senior lecturer in the department of architecture at University of Strathclyde and Professor Sergio Porta AoU is professor of urban design at University of Strathclyde

References

The fully referenced version of this paper, complete with acknowledgements, is available online, where contextual assertions and specific work by members of the team are cited. In this text, most references are under Porta, Romice (2014), where we first collated all relevant work on Plot-based urbanism.