The world watched in horror as flooding caused by hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, destroying the homes and lives of many inhabitants. Camilla Ween AoU tells the story of the pivotal role played by Tulane University in the rebuilding the city.

The world watched in horror as flooding caused by hurricane Katrina devastated New Orleans, destroying the homes and lives of many inhabitants. Camilla Ween AoU tells the story of the pivotal role played by Tulane University in the rebuilding the city.

In August 2005 Hurricane Katrina hit the gulf coast of Louisiana. It had been anticipated for several days, and the city was partially evacuated. Much of the city is below sea level and has been protected by levees (embankments) since the 1800s, both from flooding of the Mississippi River and from the surrounding lakes and bays that encircle the city. These have, over the years, and particularly following floods in 1947 and 1965, been raised, but there has been criticism of the level of protection provided and the maintenance of the levees. It was the levees in the north that failed.

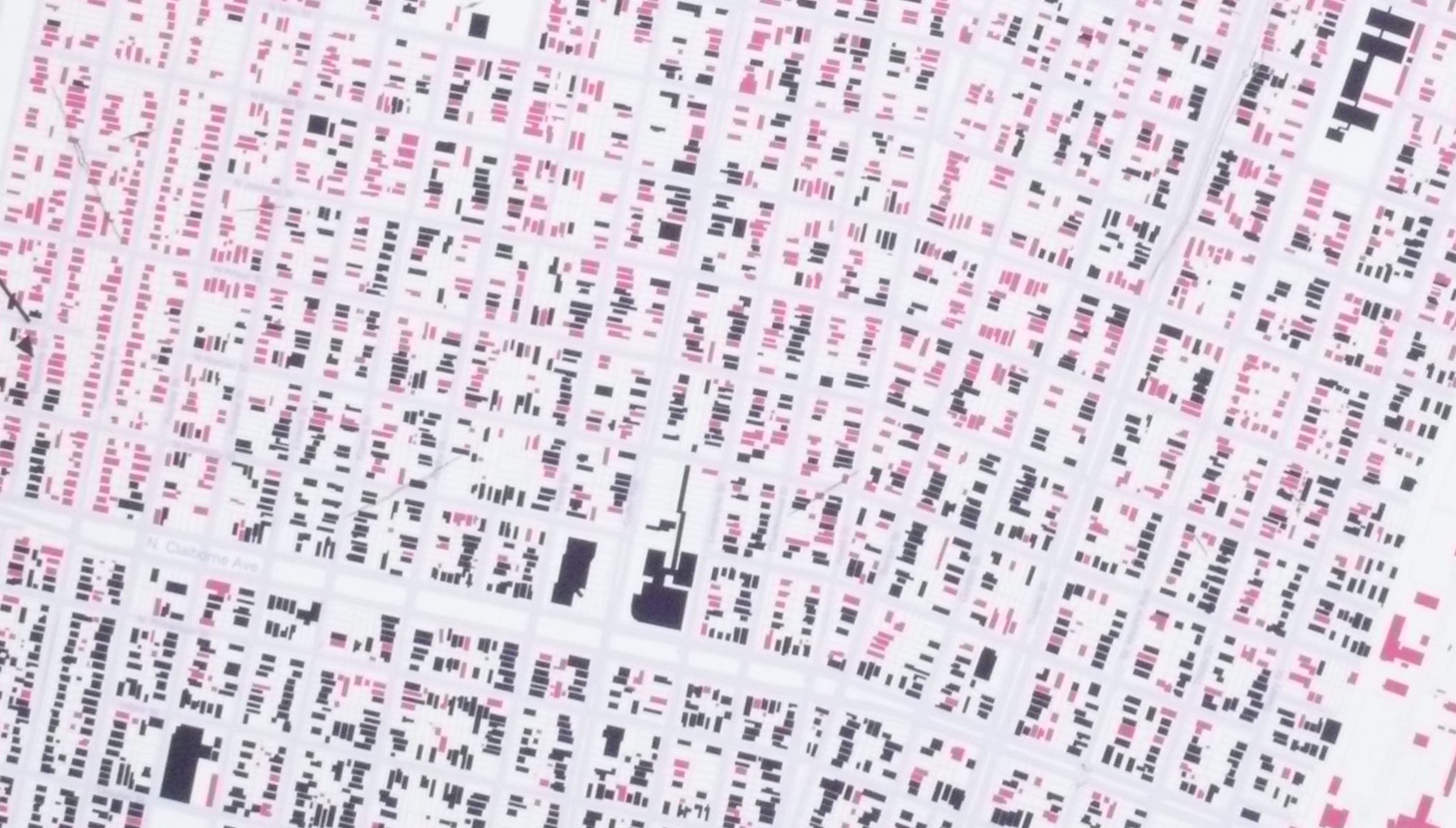

The storm surge drove water up behind the city, raising the water level behind the northern levees. They were compromised catastrophically, releasing a three-metre wall of water into the Lower Ninth Ward, which suffered the most damage and loss of life. This area still had many residents remaining as it was a poor neighbourhood and car ownership was low. Houses were ripped off their foundations and carried away. The devastation was cataclysmic. Not all the city was flooded, but much was affected, because when the power went out the sewage pumping system failed and sewers overflowed, inundating many other areas of the city. Thousands of homes were severely damaged or destroyed and thousands more were inundated with foul water, requiring total refurbishment. Indeed, many homes stood in putrid water for months. 600,000 families were homeless a month after the storm in the wider area affected. There were 1,836 recorded deaths, of which 1,000 were in the Lower Ninth Ward. The failure to maintain the levees has been blamed on lack of investment and political apathy. The total damage is estimated to be around $1tn. 10 years on, about a third of the population has not returned and many properties remain abandoned, with nature gradually claiming them.

Though Katrina was the immediate cause of the flooding, the fundamental problem lies in 85 years of destruction of the Mississippi Delta wetlands. Since 1932, Louisiana has lost 25% of its wetlands – a million acres. This destruction has been caused mainly by the oil and gas industry carving shipping channels for access into the wetlands. Over the last century this industry has been granted licences to explore, on condition that they would repair any environmental damage. However, this was never enforced. Once a channel exists, even a small storm surge will drive water inland and widen the channels, whilst also introducing salt levels that poison much of the natural wetland plants.

As a result, an area the size of a football pitch is being lost from the Delta every hour. (At this rate Manhatten would disappear within 18 months!) Furthermore, the Delta is also being starved of replenishing sediment as dams on the tributaries to the Mississippi now stop the sediment washing down. Since the 1920s, over 50,000 wells have been sunk that are causing the land to sink. The sea level is rising faster than anywhere else in the world. New Orleans is as vulnerable as ever. An intrepid local citizen, John M Barry, has taken out the most ambitious environmental lawsuit ever, against 97 oil and gas companies.

However, despite this, the current population is determined to restore and rebuild their city and preserve its unique culture. Why New Orleans Matters by Tom Piazza, written within months of Katrina, is a passionate essay on why this major US port city should be saved. After the flood there was much chaos, Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) monies were misappropriated and compensation for loss was a classic case of discrimination; white people got some, black people got less and Native Americans got nothing. In the end there was little money to rebuild the city and by necessity, most of the efforts have been bottom up.

In the immediate aftermath there was much soul searching by some of the key institutions in the city. The University of Tulane, historically an exclusive ivory tower, was in crisis. Its students had all been evacuated and so it had a real academic challenge, but most importantly, it realised that it was utterly detached from the local community. The university saw that this lack of integration with the city at large was untenable. It resolved to urgently and positively address this schism and to become part of the rebuilding solution. In December of 2005 it published a radical strategy, creating a new curriculum that introduced a public service requirement; the faculty and its undergraduate students would be expected to engage with the local community.

“Tulane University and its faculty and students will play an important role in the rebuilding of the city of New Orleans…Tulane will encourage its students to develop a commitment to community outreach and public service through the creation of a Center for Public Service that will centralize and expand public service opportunities for Tulane students.”

The Centre for Public Service was to be independent and would “seek service opportunities that contribute directly to the reconstruction of New Orleans.” Community engagement and outreach would now be a core activity.

Tulane also resolved to partner with the other academic institutions in the area to share resources in the immediate aftermath and develop collaborations and joint academic ventures. It entered into a unique partnership with Dillard and Xavier universities – the two ‘historically black colleges / universities’ – and Loyola University. It provided classroom and administrative space for Dillard and Xavier in spring 2006, while the heavily damaged campuses were being repaired. This was to be the beginning of a longer-term partnership and, according to the university, “a model of academic collaboration aimed at strengthening the institutions individually and collectively, accelerate Tulane’s ongoing diversity efforts and provide a model for others interested in closing the racial divide. The partnership will also eventually develop two new national institutes: the Institute for the Study of Race and Poverty and the Institute for the Transformation of Pre-K–12 Education” (primary and secondary education).

Tulane Architecture School has set up the Tulane City Centre, whose mission is to educate, advocate and provide design services to the New Orleans neighbourhoods. The centre has, since 2012, had its home outside the university campus, and works with local community groups to help them realise their ideas, offering planning services, architectural and graphic design, design-build services, funding strategies and community capacity building. The centre has a small staff and Tulane students provide much of the graft and design to get projects from idea to reality.

Since its foundation the centre has helped to shape and deliver a wide range of small but ambitious projects; over 40 projects have now been delivered and most of them come directly from the community. The portfolio of what has been achieved is inspiring. Most projects reflect the aspirations of a local community that wanted to recover, rebuild and reconnect to their city and each other. Many of the projects are about placemaking, creating purposeful and attractive open space where people can come together, restoring culturally significant parks and creating play-space. A significant need in the immediate aftermath of the storm was access to fresh and healthy food and so a number of urban farms and community gardens have been created. An urgent need in 2005 was the rebuilding of schools and in 2006 CITYbuild Consortium, with the help of the Tulane City Centre, launched plans for 10 schools. Culture is central to many of the projects, such as the Guardians Institute, which is a museum and multipurpose performance space, or the Candlelight Lounge, which has live music.

Wellbeing is clearly an issue for a population so traumatised and so the Pyramid Wellness Centre was established to support people with homelessness, substance abuse and mental health issues. Inevitably there has been a focus on housing, with pilot projects and prototypes for self-build and affordable housing. There is also an emphasis on commercial property, restoring historic buildings and street fronts and a transport project to improve transit connectivity and interchange. They are mostly small and medium-sized projects, but they each bring valuable assets as well as learning and confidence to the local communities and unite them around common goals.

A project that stands out for its enlightened approach is one called Grow Dat Youth Farm, which was conceived to bring about personal, social and environmental change within the local communities. The Tulane City Centre partnered with the New Orleans Food and Farm Network and City Park to create a youth training scheme centred on urban agriculture. The seven-acre site has a beautiful classroom facility built from steel containers, with a covered outdoor area for lessons as well as extensive cultivation areas. The principle is that young people are invited to apply for the programme and, if accepted, they are expected to treat the appointment as a job, show up on time and engage fully with the activities. The young trainees are taught urban agriculture, food economics and cookery. The aim is to foster leadership, team working and environmental stewardship amongst the diverse young people who join the programme, through the collaborative work of growing food. It is a truly inspiring project that gives young people an opportunity to work in a beautiful setting and get valuable skills training.

How Tulane has played a pivotal role in New Orleans’ recovery is an exemplary illustration of how academic institutions can bring together the aspirations of local people, the energy of students and the professional know-how of faculty to make things happen. This is a model that could be exploited in any regeneration area. It stands in complete contrast to Brad Pitt’s very well intentioned Make It Right Foundation, which has explored sustainable housing typologies and, using famous architects such as Ghery and Adjaye, built a few prototypes in the Lower Ninth Ward. Nice as they may be, they have done little to address the urgent needs of the poor and disadvantaged in New Orleans and will most likely not be occupied by them in the long term. What the Tulane initiative is doing is acting as a broker and genuine partner to make regeneration projects reality and provide professional advice and encouragement to local communities that have probably never had to assemble the collective energy or skills to manage complex projects. It has also done much to foster healing of communities suffering devastation as well as social exclusion.

Camilla Ween AoU is a Director of Goldstein Ween Architects.

All photos copyright Camilla Ween