The plight of Detroit is well known, but perhaps less so are the lessons for good urban practice. Dr Gareth Potts reflects on areas where Detroit and older UK cities might have valuable dialogue.

Last year a Guardian headline asked: “The north-east of England: Britain’s Detroit?” Having lived and studied in both places, I hoped that the article would see some sharing of strategies for older industrial cities. Yet nowhere, in the piece or subsequent debate, was there a sense that the US city might offer lessons or have shared challenges.

Certainly, the differences between Detroit and older UK cities are stark: the nature and scale of problems; racial make-up; the role of charitable foundations (both local and national); and the nature and importance of government (both local and central). But, there really are areas where UK urbanists can have a good old chat with their Detroit counterparts.

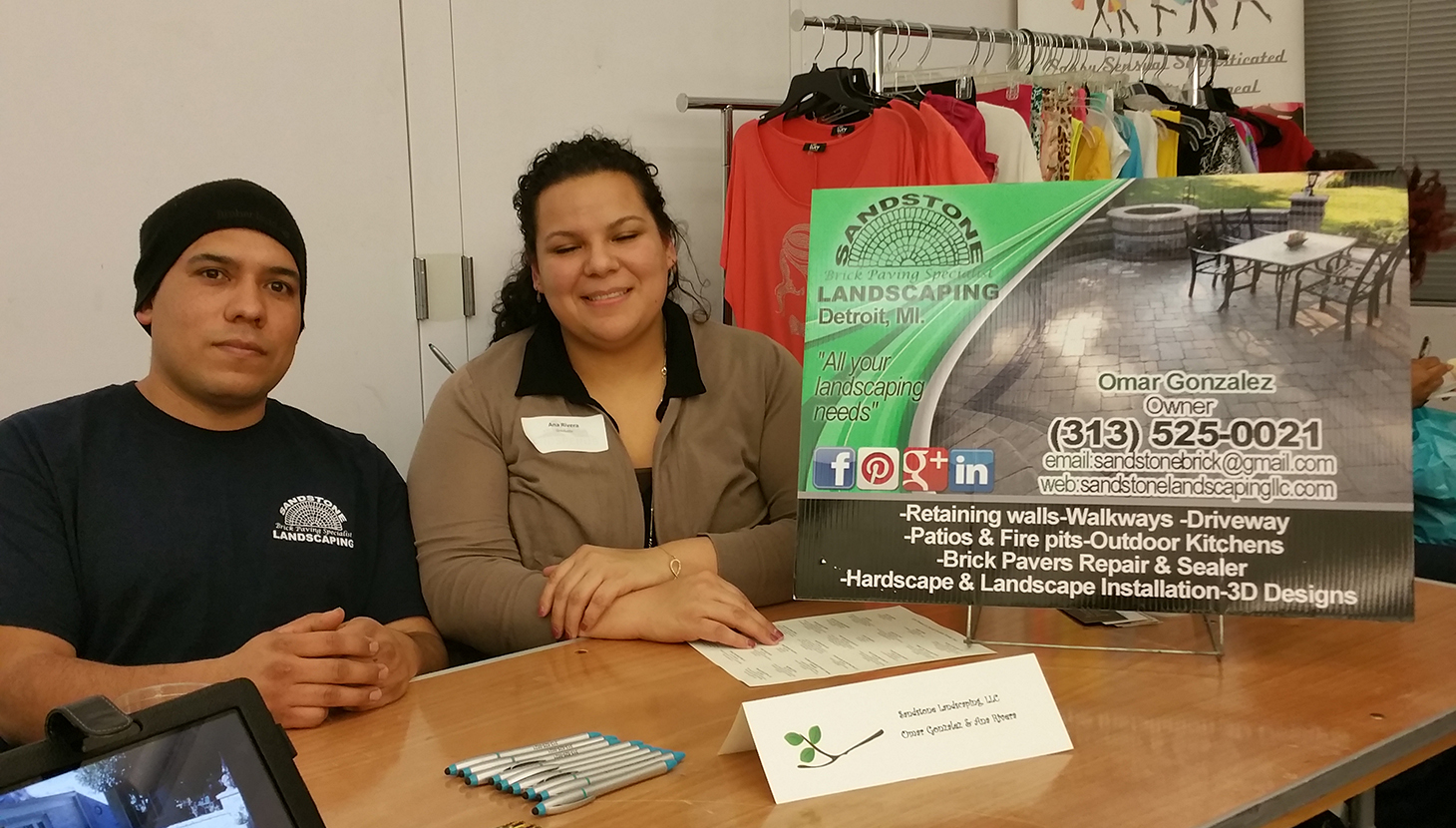

Detroit is now wise to the fact that immigrants often boost local economies – one in three Michigan tech start-ups in the last decade were led by an immigrant. Southwest Detroit, a heavily Latino area, is frequently hailed as the most revitalised working-class neighbourhood in Detroit.

Cities are constrained by national immigration policy but can still make themselves attractive to recent arrivals. The City of Detroit is now a participant in ‘Welcoming Cities and Counties’ – a national programme that works with local governments to create immigrant-friendly environments through measures such as English classes, small business support, and programmes on U.S. culture.

Additionally, a nonprofit, Global Detroit, has helped to launch several initiatives including: an international student retention programme; a programme to integrate skilled immigrants and refugees; an online database and network of organisations and groups serving immigrants; a professional networking programme; and a micro-enterprise development programme (ProsperUS Detroit).

Cities need to show their best side to visitors, prospective inward investors, entrepreneurs, employees and, even, many unaware locals – this means nightlife, sporting, cultural and leisure activities, as well as great places and buildings. Detroit Experience Factory (DXF) is a nonprofit that seeks to do just this – not least through bus and walking tours of the city (which some 12,000 people took in 2014). Set up and led by a local woman who loves the place, this is not your stuffy visitor bureau or place promotion effort.

The founder and CEO of one of the city’s major employers, Quicken Loans, has often stressed the need for the city to attract and retain millennial graduates through downtown offices near good cultural and leisure opportunities. This is true but Detroit and many older UK cities could also focus on attracting groups that are outside of the workforce and generally with a reasonable amount of disposable income – so retirees and students, in particular.

The metro area is home to one of the U.S.’s largest academic research clusters – dominated by Michigan State, the University of Michigan and Detroit’s Wayne State University (WSU). Efforts are afoot, as in many older UK cities, to ensure that these institutions are plugged into their local economy.

These include the University Research Corridor – a programme that jointly promotes these universities’ impact on the state’s economy and that also supports some joint projects (such as Accelerate Michigan, an alliance with the state’s largest job providers, which focuses on fostering economic innovation and entrepreneurialism). Michigan State’s Center for Regional Economic Innovation also fosters best local economic development practice around innovation.

Each university also has its own economic development work. For example, TechTown Detroit, a nonprofit co-founded by WSU in 2000, now includes support for new and existing businesses in under-resourced neighbourhoods and a multi-strand initiative focused on the development of talent, technology, deal flow and innovative startups.

WSU also now has an Office of Economic Development that oversees several business support programmes, including a student entrepreneurship centre and The Front Door for Business Engagement.

Through the use of public-private partnerships, Detroit has seen the introduction of some terrific public spaces in the last decade or so. These include the (reclaimed) Riverfront and the (rejuvenated) Eastern Market as well as the award-winning Campus Martius Park with its cultural events, urban beach, outdoor seating and ice rink.

Rivard Plaza – the first section of the riverfront that was reclaimed. ph. Detroit Riverfront Conservancy

As the American Civil Liberties Union of Michigan has articulately argued, true public spaces have to permit orderly campaigning and protest. Since the park and Riverfront are managed by nonprofit conservancies whose security is then contracted out, the city (which wholly and partly owns the land, respectively) has now issued guidance (also applicable to city parks) stressing what these constitutional rights must mean in very practical terms.

Place-making is also occurring in the often less affluent neighbourhoods. These include some bottom-up initiatives such as The Alley Project, which centres on an alley converted into a local meeting space that local kids decorated with street art. There are also schemes generated by Foundation and State competitions, for example, in Brightmoor, in the city’s north west, plans are being put in place for an outdoor learning area featuring native plants, a walking tour, fire pit and seating.

The other key place-making development is the creation of links between places. This can increase exercise and use of places as well as help limit car use.

Highest profile here is M-1 Rail – a 3.3-mile streetcar system, being delivered by public-private partnership. This will run past the sporting, cultural, higher education and leisure assets between downtown (and its orbital People Mover) and the New Center area (with its links to the rail line to Chicago and the city bus system). The aim is to quickly move large numbers of people along one of the five ‘spine’ roads that radiate from downtown.

There may even be a proper metro- wide mass transit system if, late next year, voters across the metro area counties approve some of their property taxes going to support the new Regional Transit Authority’s plans. Such metro votes, already passed for the Detroit Institute of Arts and Detroit Zoo, are the sort of choice UK metro devolution advocates yearn for!

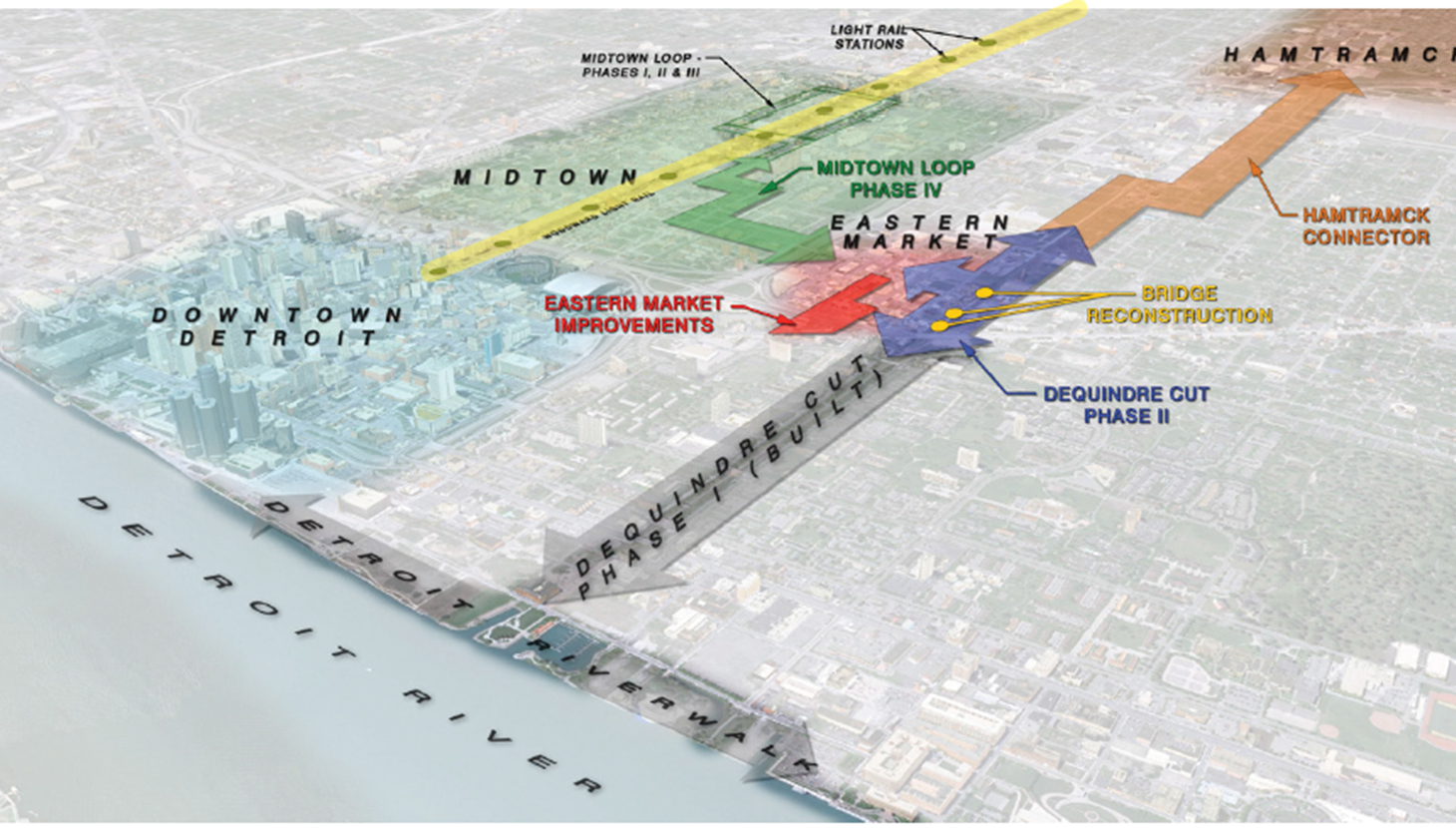

At an even more affordable level are the many efforts, orchestrated by the nonprofit Detroit Greenways Coalition (DGC), to increase routes for use by cyclists, joggers and walkers. One such route takes in the Riverwalk, Eastern Market, the Dequindre Cut (a 1.4 mile re-purposed rail line that links the two) and has recently been expanded to Midtown a half-mile to the west and Hamtramck, a town several miles to the north.

The City’s Detroit Land Bank Authority (DLBA) takes on residential properties where the owners have not paid taxes for several years. It looks to sell the better homes through online auction. Bids start at $1,000 and a new owner has six months to complete any repairs needed – so some similarities with the ‘homes for a pound’ strategy adopted in several UK cities.

The DLBA engages in demolition where properties are beyond repair. Their efforts to eliminate vacancy are not helped, however, by the fact that, since the 1950s, metro Detroit has consistently seen homebuilding outstrip household growth. Older UK cities are fortunate that Green Belt policy, brownfield incentives and NIMBYism have largely kept such sprawl in check.

The Detroit Future City (DFC) framework, the result of extensive public consultation, includes strategies for Detroit’s transformation – such as focusing residential and economic growth in key locations and outlining potential uses for larger vacant areas (storm-water management; urban agriculture and forestry; recreation; greenways etc.).

Whilst many UK cities have been hit hard by cuts to the funding they receive from national government, wrestling with austerity has long been the name of the game for the City of Detroit government.

So, for example, 77 of Detroit’s 307 parks are currently ‘adopted’ by churches, community groups, businesses and nonprofits. Adopters agree to keep parks rubbish-free and to mow and weed them every two weeks in summer. A few even put on activities such as ice hockey, baseball and yoga. The city, in addition to maintaining the other parks, monitors quality and installs a sign at each location recognising the adopter.

Whilst Detroit’s plight has been well documented by journalists and filmmakers, it has often consisted of seeing it with detached amazement rather than somewhere that urbanists can exchange good practice with. I hope this piece has encouraged you to see it in a different light, to engage with in some way and maybe even pay a visit!

Dr Gareth Potts, based in Washington D.C., is founder of The New Barn-Raising, an international network to encourage sharing of best practice around ways to sustain community and civic assets thenewbarnraising.com.