Background

Until a certain time of my life, the city – be it London, Paris or my native Milan – was a place that was meant for me. I related to it, I saw myself in it. I explored its streets and venues, I used its services. I took the space I wanted, with the exception of maybe less safe neighbourhoods or places I simply couldn’t afford to spend time in. My biggest constraint was probably being a woman, which in itself has huge spatial implications and a set of barriers (but if I digress onto this I might write another essay! Maybe let me just point you to this Ted Talk by Shreena Thakore for a bit of an introduction to the topic….). But at least this issue was shared with quite a lot of people around me, around half of the population in fact. And although there is still so much that has to be done in this field, I could access networks of support, find literature, debate this in class, at the pub or at the family table. Until a certain point, I felt like overall the city was a place where I belonged. To be exact, actually, I thought it was a place where everybody belonged. I belonged there just as any other person did, or so I thought…

Then, I became a minority. And the city changed with it. It was suddenly mapped out differently – with areas that became less accessible, either to me or other members of my community, the messages shared around me – in publicities, art, announcements, reminded me of my difference – undermining me, and I started having to think about safety on my own street when holding my girlfriend’s hand. The city was not planned by or for everyone – my until then straight cis-gender privilege[1] just hadn’t allowed me to see it. And as somebody that ‘passes’[2] as non-queer, and considering other layers of privilege, I suspected there were many more issues faced by the wider and diverse LGBTQIA+[3] community in terms of their lived experience of cities that were not only not being addressed or widely discussed.

#MyQueerCity: Opening up Dialogue

The Small Grant Scheme from the Young Urbanists Network at the Academy of Urbanism, along with the support for the project by the Building and Social Housing Foundation (BSHF), has allowed me to have the space to start joining up conversations happening around the inclusivity of Gender and Sexual Minorities in experiencing urban space… and thinking further in terms of citymaking and transformational action. I decided to dive in from the perspective of people’s lived experiences and ambitions. In fact, whilst preliminary research was useful in identifying key issues and also finding that the evidence that currently exists does indeed point towards the inequalities experienced by LGBTQIA+ people in cities (see powerpoint for findings), this project was always going to be about dialogue first. And I felt this had to happen without pre-embedding discussions in existing theoretical frameworks, and stirring conversations before they’ve had the chance to take shape, potentially excluding and erasing relevant insights.

This led to the #MyQueerCity workshop on Feb 27th 2017 – with the use of the hashtag being chosen deliberately as an invitation towards conversations. On this occasion, LGBTQIA+ people were invited to a free workshop aimed at exploring what an ideal inclusive city would look like from a Gender and Sexual Minority perspective. Participation was also encouraged online through social media for people that couldn’t make it to the workshop.

You can find the video about the workshop here:

The workshop imagined that LGBTQIA+ people had a ‘magic wand’ to design the city they wanted. This ‘magic wand’ idea was born out of an informal test run of #MyQueerCity workshop in January, which I had improvised at an event called Devoted and Disgruntled where anybody can stand up and ‘call a session’ on a topic of interest. Here a group of about 15 people joined in and shared their ambitions for LGBTQIA+ inclusion in cities – and although there were many really valuable and interesting points, I was struck by the fact that most discussions revolved around making LGBTQIA+ spaces better, and making the arts sector reflect LGBTQIA+ issues and people more significantly. In sum, improve the spaces in which Gender and Sexual Minorities already have a presence, as opposed to having the confidence to envisage the freedom of having a say in ALL urban spaces/places/infrastructure/services.

For the official #MyQueerCity workshop – I wanted to emphasise that this was about rethinking cities so that they matched needs, hopes and dreams… no matter how ambitious or currently unfeasible these were. It was an opportunity to regain space over discussions, to be empowered to make demands and to shape urbanscapes to reflect and include the beautifully varied and multi-faceted LGBTQIA+ community. (Turns out the magic wand seemed to result in the abolition of capitalism in most discussion groups apparently! It’s a pretty powerful wand you see…).

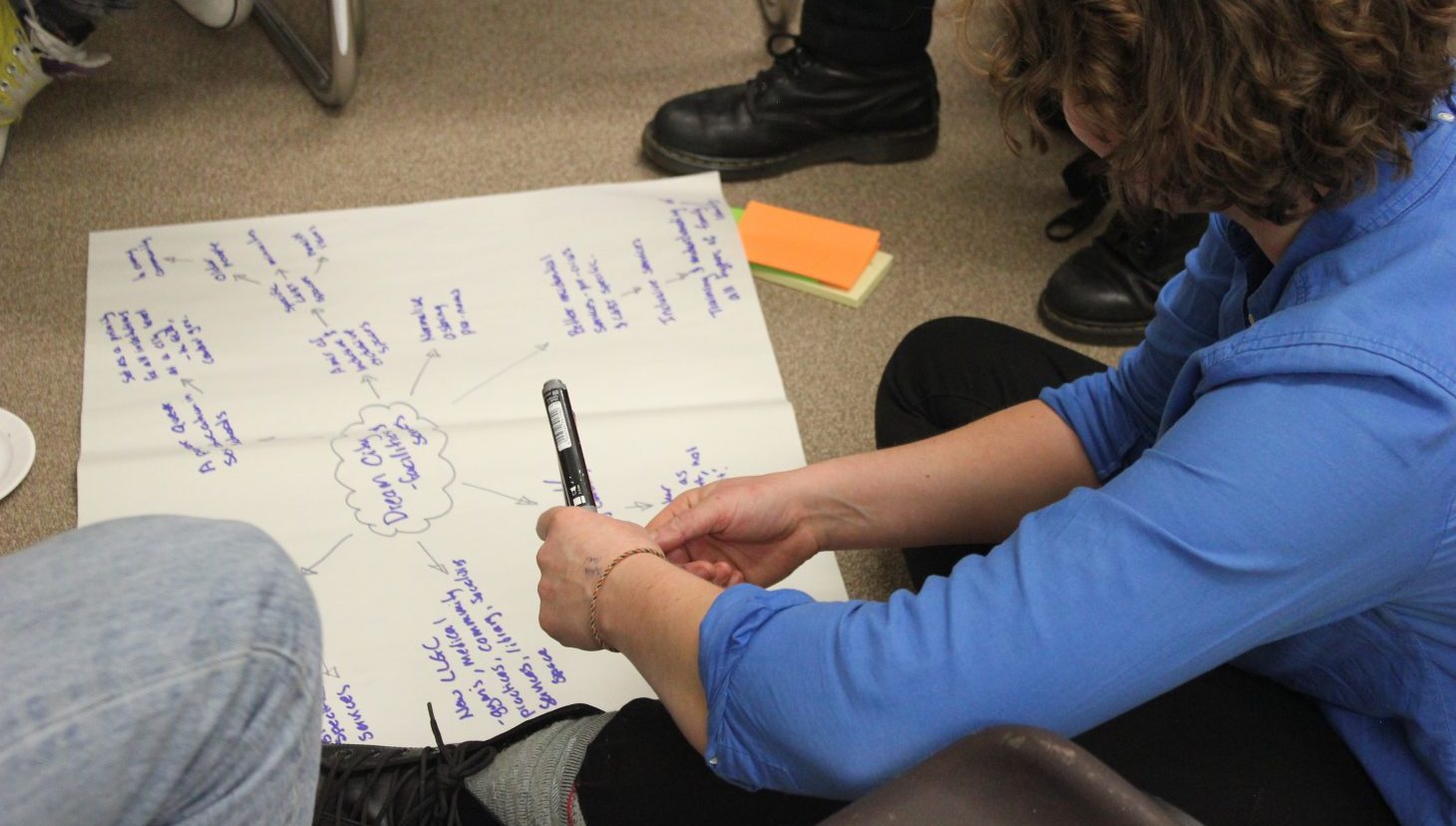

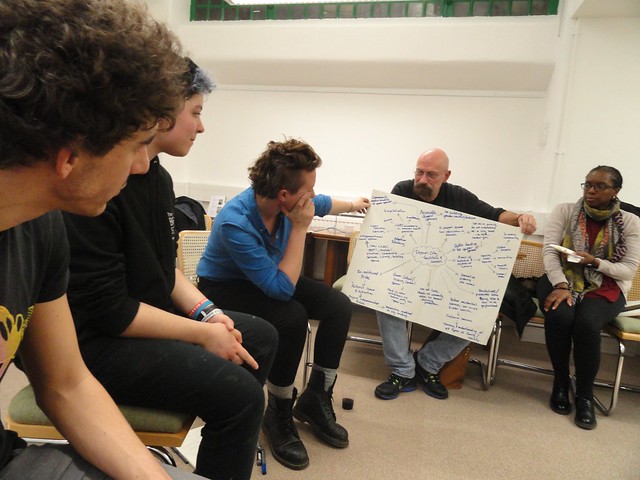

To help focus discussions around various aspects of urban life – the attendants were organised in three groups, exploring perspectives around either: 1) housing 2) services and facilities and 3) infrastructure and public space. Attendants were also encouraged to digress from these specific topics since there might be a whole set of needs and dreams that do not strictly fall into these categories. All groups then fed back to the rest of the room, which then led to a discussion around the issues raised, and unpicking some of the more complex dynamics of creating a city for all in a very mixed society with layered identities. We also discussed WHO had the power to change things.

So… what do LGBTQIA+ people want for their cities?

The results were then presented publicly at a follow up event on 25th March called ‘Citymaking: voices from the LGBTQ+ community’. To help draw parallels between the issues and ambitions raised around #MyQueerCity, I organised the ideas from the workshop into theme. Based on the reflections of our focus group, what LGBTQIA+ people would see as inclusive cities are places that offer (see full presentation below):

- Visibility (of people and issues); representation of LGBTQIA+ amongst decision-makers, built environment professionals, public people of influence; presence in in public space.

For example; art, advertisement, public campaigns by or about LGBTQIA+ people; educational curriculums that explore highlights contributions and issues of Gender and Sexual Minorities, widespread understanding and celebration of LGBTQI+ history/culture (museums, queer events, Pride, etc.)

- Adequate spaces: spaces/infrastructure designed to responds to people’s needs.

For example; accessibility, gender-neutral/all-gendered bathrooms, etc.; ensured safety in both public and private realms (street, public transport, housing, etc.); inclusionary spaces where all LGBTQIA+ people feel comfortable and allies are welcomed; perhaps counter-intuitively but importantly – exclusionary places where minorities within the LGBTQIA+ sphere can meet (e.g. less represented groups such as intersex or asexual people, or Black and Asian Minority Ethnic (BAME) or religious people, or youths…); spaces need to be varied so they can be suitable to different preferences and needs (e.g. venues that do not revolve only around drinking or loud cheesy music); and affordability of queer spaces and ‘gaybourhoods’ (‘Can any of us actually imagine living in Soho?)

- Adequate services: services designed so that they are appropriate and fit needs of LGBTQIA+ people

e.g. structures in place to ask LGBTQIA+ what these needs are (instead of assuming them…), staff trained to understand and address LGBTQIA+ issues across sectors (medical services, police, transport, prison, elderly care, asylum seeker services, etc, recognition and elimination of individual and institutional heteronormativity[4] and cisnormativity[5], special attention to mental health (as currently this disproportionately affects Gender and Sexual Minorities), LGBTQIA+ specific services (e.g. youths, trans, housing, etc)

- Community solidarity and action: mobilisation and activism for LGBTQIA+ rights and wellbeing

e.g. opportunities for LGBTQIA+ to explore their heritage/identity/history in order to understand legacy; spaces of engagement and mobilisation around LGBTQIA+ issues (even in an inclusive city, LGBTQIA+ culture and needs would always be in evolution and would need networks to support positive change and exploration); alliances with other struggles and groups (e.g. people with disabilities, refugees/asylum seekers, etc…Remember Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners?); take over! (i.e. direct action through re-politicising Pride March, space-hacking, mapping, tours, street art/street messages, etc)

- Financial and political support by society and authorities: Recognition of issues specific to Gender and Sexual Minorities and explicit commitment by public authorities to address them;

e.g. public provision (funding of education programmes, LGBTQIA+ specific services and spaces, cultural events, etc.); rights-based approach – whereby inclusion and equity are seem as rights and are non-monitarised; monitoring of outcomes of LGBTQIA+ issues and the programmes set up to tackle them

- Intersectionality[6]: Recognising the overlapping or intersecting of social identities, and addressing the relation between various systems of oppression and discrimination – in order to make sure no members of the LGBTQIA+ community are left behind.

e.g. understanding privilege and lack of it within LGBTQIA+ groups; solidarity and further engagement with underrepresented and/or disadvantaged groups amongst Gender and Sexual Minorities, acceptance of different needs/spaces; space and openness to dialogue across different realities

Who has the power to change things?

We developed on the question concerning who should do something about all this. Interestingly, at the #MyQueerCity workshop, the most consolidated and unanimously shared opinion is that – the main people responsible for changing things is the LGBTQIA+ community itself. This can be done through collective support and solidarity amongst the community, and the facilitating of alliances and dialogue, along direct action and activism to make space for LGBTQIA+ people within the policy and practice of citymaking, but also everyday experiences of space and place. Calling out on institutional heteronormativity and cisnormativity was also seen as a key effort that had to be supported, along with remembering to bring change in the spheres of influence we have through our jobs and roles. Finally, setting up and running organisations that help tackle the issues we raised above.

While it is amazing that the LGBTQIA+ community takes ownership and responsibility over this role as changemakers – which is very empowering and inspiring, I believe it does also unfortunately reflect a degree of lack of confidence and trust in city authorities and policy makers to spontaneously act upon these issues. Some participants did express their view of these actors as key people to get on board and interact with in terms of achieving change – and in particular demanding real commitment on their behalf, and the re-design of policies/services/infrastructure to be truly inclusive.

We should also mention the role that allies[7] can play in supporting LGBTQA+ community members – noticeably in staying informed and supporting the spreading of questions regarding gender and sexual minorities, fight battles with LGBTQIA+ community everyday (not just during Pride when it’s all fun and full of glitter), and gaining greater awareness of patterns of heteronormativity and cisnormativity – and committing to challenge them.

As an illustration of people that are actually ‘doing something about this’, Lucy Warin from Sexual Avengers and Michael Nastari from Stonewall Housing were also invited to talk about their work. The idea was to not just focus on the aspirations we still haven’t achieved, but to also reflect on the work that is currently done by the LGBTQIA+ community in terms of inclusive citymaking. In fact, although inequalities must be recognised, the aim of the project is not only to envisage LGBTQIA+ people as victims of the system, but also as actors of its transformation and change. For example, Lucy presented her views on ‘Activism, queerspace and radical queer citizenship’ – focusing on the use of queer as a verb (queering) illustrating the call to direct action in order to reclaim space and impact on the urban fabric. She cited hanging a huge ‘Queer Solidarity Smashes Borders’ from Vauxhall bridge in response to Trumps election, space-hacking the city with commemorative plaques[8] of LGBTQ+ activists during LGBT History Month, but also re-thinking of how to re-politicise Pride, focus on saving queer spaces (and not just gay bars – think of wider initiatives such as LGBTQ+ centers, community cafes, etc), and working within a group that understand people’s vulnerabilities, for example in terms of mental health, and create safe spaces for people of different background or age.

Michael focused his presentation on the role of Stonewall Housing as the only comprehensive LGBTQ+ specific housing charity in the UK, offering supported housing to LGBTQIA+ youth, and a whole range of advice and support services. He explored the type of initiatives that Stonewall Housing is involved in, along with the partnerships and projects developed to address issues such as mental health, domestic abuse, older age, etc. The work of Stonewall Housing really highlights some of the vulnerabilities that are still faced in LGBTQIA+ communities in terms of increased risk of homelessness and lack of appropriate services in supported housing and care homes. They work both at individual level, and at sector wide level to train housing providers and influence policy. They were recently finalists of the World Habitat Awards – the innovative and sustainable international housing awards run by BSHF (more insights from BSHF on Stonewall Housing’s work here).

The event ended on questions and discussions with the public – of which three particularly subjects stuck in my mind. We talked about gentrification on the community. You might have heard the argument that gay communities gentrify neighbourhoods – referring typically to affluent white double earning male gay couples with no children. Examples of this can be effectively found that would reflect this – when I was living in Washington DC I’d say the Dupont Circle gaybourhood fitted this narrative – nonetheless it was pointed out that this is a simplification, as many LGBTQIA+ people, groups and services do not fit this profile and are often gentrified out of spaces as opposed to gentrifiers. Nonetheless, amongst us we did not know of comprehensive research on this topic (if there are any volunteers out there that would like to do a PhD on the matter that would be great, please let us know your results!). We also talked about the relationship between capitalism and LGBTQIA+ issues… it’s quite a large topic, but we talked for example how – although they might be linked to greater visibility and cultural acceptance, LGBTQIA+ core issues/rights lose part of their nature/impact if they are absorbed by the corporate sector as a form of positive advertisement e.g. corporate presence at Pride, use of gay imagery in publicity… The third discussion that struck me was linked to a question on whether people in the room could think of cities that had particularly good practices in this field… and… there didn’t seem to be many examples based on the experience/knowledge of the people in the room. Vancouver was cited as quite an inclusive city that had developed quite an active approach to securing the safety and acceptance of LGBTQIA+ people (e.g. more visibility of LGBTQIA+ issue at policy level, high level of training and response to hate crimes, etc), but the fact that we didn’t have examples spring to mind is quite telling of the lack of well-developed comprehensive solutions.

Limitations

The #MyQueerCity workshop and follow up event were invaluable opportunities to collect different powerful views from LGBTQIA+ people (and allies in the last event). We all agreed that these discussions were by no means exhaustive, and that thinking of CITIES is a huge topic of which we only scratched the surface. There was a lot of energy in the room to explore all of these further. We also realised there were some biases with this focus group – first of all, it took place in Central London – which although maybe is a place that exacerbates dynamics happening around the country and in different cities – it is also a very specific context, and LGBTQIA+ people in secondary or small cities, or in different areas of London might be encountering a whole different set of constraints and have other ambitions. Although I wouldn’t say that the group of participants was homogeneous, it was also not fully representative of the diversity LGBTQIA+ community in terms of age, race, religion, income, social capital, and only some gender and sexual minorities were present. The sample was relatively small (15 people in the test workshop, 13 in the official workshop, and about 25 in the public event). Nonetheless, this was a good start in terms of opening dialogue – and there has been an interest to replicate this process in other place, which could potentially lead to very interesting further results.

Looking forward…

As this project was taking shape, one of the comments that kept on coming up was that ‘it’s great to have the space to talk about this – but this feels like this should just the beginning of something bigger…’.

Which was great to hear (albeit slightly daunting!). So where do we go from here, and what can you do to join in/ help out?

First of all, let’s keep in touch! In the aftermath of the event – we started an email thread that you can join by emailing me at mariangela.veronesi@bshf.org and letting me know you’d like to be added. (This might be shift onto a platform like faceboook in the future, but for now it is in the form of an email thread). This has been the main place to share updates/materials and upcoming events so far, and it looks like there might be some possible events coming up that have spun off from this work in the next few months… so … watch this space!

Secondly, let’s find out more. Some of us have started sharing information we find on other people that have written/talked about LGBTQIA+ spatial/urban/geographical issues, which helps us map out findings so far and increase our knowledge of discussions around queer spaces and urban inclusion. Please feel free to share relevant resources, or examples of good practices, with me at the email mentioned above, or through twitter @MariVeroUK, or just use the hashtag #MyQueerCity

In addition, in terms of finding out more about our communities and what Gender and Sexual minorities want and need for their cities, if anybody would like to run a #MyQueerCity style event, please do feel free to do so! Either in other areas of London, or anywhere across the UK… or even abroad! Just kindly let me know so we can understand and capture the collective legacy of this project and tie experiences together/support each other.

Thirdly, let’s act together! Consider joining a group that does some work near you – for example Sexual Avengers if you’re in London, or volunteer for Stonewall Housing, or some of the suggested organisations mentioned at the end of the powerpoint. Or if – like me and, believe it or not, many other people, you don’t live in London, please have a look around you for relevant groups that have an impact on how LGBTQIA+ people can have an impact on city making (and let us know about them! Would be great to connect). Or… start your own and become queer space activist, maybe with the support of people around you that can help you out!

If starting or joining an organisation isn’t your thing or you are faced with barriers that prevent you to participate in group action, don’t forget you can also make contributions through your daily lives and actions. Think of what power you have within your work or other places in society and how you can use it to help advance LGBTQIA+ inclusion in cities. For example, you can: question decisions made on spaces around you (e.g. ask your pubs, museums, offices to change to gender neutral toilets; request your community centre to have LGBTQIA+ inclusive language/imagery, etc.), start discussions with people that might not have considered such issues before (e.g. work with your colleagues to make sure your work is LGBTQIA+ inclusive, both within and beyond the office space, or propose LGBTQIA+-specific projects; talk about the importance of understanding the origins of Pride to friends attending Pride events; etc),you’re your power as a citizen to influence policy and practice (e.g. write to your MPs to raise your concerns about issues affecting the LGBTQIA+ community in your constituency), etc.

If you have any other suggestions please let us know about it – we’d love to hear from you and help build on the solutions that can help queer our cities and transform them into inclusive and diverse spaces.

Conclusions

I would just like to close with a thank you to all those that believed in this project and helped start these much needed conversations. In particular, thank you to the Academy of Urbanism – Young Urbanists Network for the grant and the logistical support that made this project come to life, in particular Bright through her amazing work! Thanks also to the Building and Social Housing Foundation for providing the working time to develop and deliver this project, along with inputs, encouragement and support, and the belief in addressing the inequalities faced by LGBTQIA+ minorities in housing and urban environments. Infinite thanks also to Claire Malaika Tunnacliffe for the continued inspiration and enthusiasm throughout this project – which has effectively become a shared flow of thoughts and new findings, which seems to be leading towards interesting horizons! (follow @C_Mali on twitter and www.inthestreets.city for updates). Cheers to Lucy and Michael for speaking about their amazing activities at the event, and for their continued work as part of networks that deliver real solutions and spaces of solidarity. Finally – many thanks to everybody, queer, questioning or ally, that has come or taken an interest in the project – and that will participate in shaping the inclusive cities of tomorrow!

Whilst we work towards it, at least I can say that this project has personally made me feel more empowered to take space as an queer citizen, to have a say, and to once again see the city as a place that I have the right to claim as belonging to me and the members of the diverse and multi-faceted rainbow community.

Footnotes

[1] Straight privilege and cisgender* privilege refer to the privilege of not being faced with a set of inequalities that affect non-heterosexual and non-cisgender people. This can be linked to a lack of awareness of the abovementioned inequalities, and therefore a belief that such inequalities do not exist, based of one’s own observations or understanding – as opposed to on the understanding of non-straight or non-cisgender people

(*note: definition cisgender: person that “identifies as their sex assigned at birth […]. A cisgender/cis person is not transgender. “Cisgender” does not indicate biology, gender expression, or sexuality/sexual orientation” http://www.transstudent.org/definitions )

[2] ‘passing’ indicates observers assuming that you are part of a different, more ‘accepted’ community than one that the individual is part of. E.g. If a person passes as straight, most people will assume they are heterosexual, for example based on one’s physical appearance, clothing style.. and will treat them as such

[3] The acronym LGBT stand for Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans, Intersex, Asexual and the + represents other Gender and Sexual Minorities (more extensive list of sexual minorities here)

[4] Definition: heteronormativity – noun : the assumption, in individuals or in institutions, that everyone is heterosexual (e.g. asking a woman if she has a boyfriend) and that heterosexuality is superior to all other sexualities. Leads to invisibility and stigmatizing of other sexualities. http://itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2013/01/a-comprehensive-list-of-lgbtq-term-definitions/#sthash.gALvKXow.Z62mM0u8.dpuf

[5] Definition: cisnormativity: the assumption, in individuals or in institutions, that everyone is cisgender, and that cisgender identities are superior to trans* identities or people. Leads to invisibility of non-cisgender identities. http://itspronouncedmetrosexual.com/2013/01/a-comprehensive-list-of-lgbtq-term-definitions/#sthash.gALvKXow.Z62mM0u8.dpuf

[6] Definition: the theory that the overlap of various social identities, as race, gender,sexuality, and class, contributes to the specific type of systemicoppression and discrimination experienced by an individual http://www.dictionary.com/browse/intersectionality

[7] people that are not LGBTQIA+ but that are actively supportive of their rights

[8] http://www.huckmagazine.com/perspectives/activism-2/sexual-avengers-blue-plaques/

You can see the Flickr album from the #MyQueerCity workshop on the Academy’s Flickr page by clicking on the image below.