Following the recent publication of Urbanism, a compendium of the Academy’s Great Places from 2009-2013, Nicholas Falk AoU asks whether quantitative data could be used to support the qualitative assessments of the award judges. Two recent reports, ‘Competing with the Continent’ from the Centre for Cities, and European Union study: ‘The State of European Cities 2016’ may provide some clues.

The AoU’s strength, like the Good Food Guide, lies in the experience of its members. But its declared aim to ‘learn from place’ is ‘fiendishly difficult’, as the authors of Urbanism conclude. Hence there are no ‘templates or simple best practice lessons’ in this beautifully illustrated compendium. But even a food critic takes note of the cost of the meal, and judges more than just the taste. So after 10 years of looking at towns and cities all over Europe, are there ways of refining our judgements and recognising transformation in difficult circumstances?

Starting with the economy

Huge progress has been made in recent years in handling ‘big data’, with GIS (Geographic Information Systems) allowing comparisons that transcend local authority boundaries. These lead to various forms of indices or ranking, such as those published by Monocle or the Economist Intelligence Unit. It should be worth looking at the places that score highly but that have not yet been assessed by the Academy. A good place to start is the Centre for Cities report, Competing with the Continent, on how UK cities compare with their European counterparts1. Backed up with a data tool that allows you to make your own comparisons, the report compares 330 cities across 17 European countries.

The report shows how poorly British cities generally compare with their Continental counterparts, apart from London and a few exceptional stars like Oxford and Reading. Indeed, the Centre for Cities considers the UK ratings to be most similar to places in Eastern Europe on factors such as skills, innovation and productivity, which is what they regard as most important. The poor showing can partly be explained by suburbanisation, which has in the past attracted the most talented to move away, and also by poor transport links and an over-academic form of education.

But there are also important political, geographic and historic factors that the report does not bring out. Provincial cities on the Continent benefit from having played much wider roles, which has left them with a legacy of fine buildings and public places. They also generally have stronger economic bases, particularly in smaller cities where there is often still a major manufacturer in premises that in the UK would have been redeveloped for retail. As it is businesses, not local authorities that compete for markets we would do well to pay more attention to peripheral industrial towns that have ‘turned around’ such as Donostia / San Sebastián in the Basque Country (the winner of the 2015 European City of the Year award), or Kassel or Leipzig in Germany, which are profiled in Good Cities Better Lives2.

Connecting cities

The UK’s evolution as an island off the coast of the Continent has also had a profound influence on the quality and size of its cities as well as their roles. While Britain may have benefited from early industrialisation in the first part of the 19th century, thanks to plentiful coal, and was well suited to imperial trade thanks to a host of ports, its cities are not so well-connected today compared with those on the Rhine or other great rivers.

Maps within the Centre for Cities report highlight the close proximity of most British cities to each other, as also is the case in Belgium and the Netherlands. However in France and Germany, where towns are more dispersed, there are well-connected clusters outside the capital city. For example, Heidelberg, which rates far above Oxford in patents per 100,000 inhabitants (a measure of innovation), undoubtedly benefits from its location in the high-tech state of Baden Wurttemberg, and proximity to industrial powerhouses such as Karlsruhe, to which it is linked by both tram and trains. As the report stresses though, large cities are generally more innovative than smaller ones, agglomerations can fight back if they have the right governance.

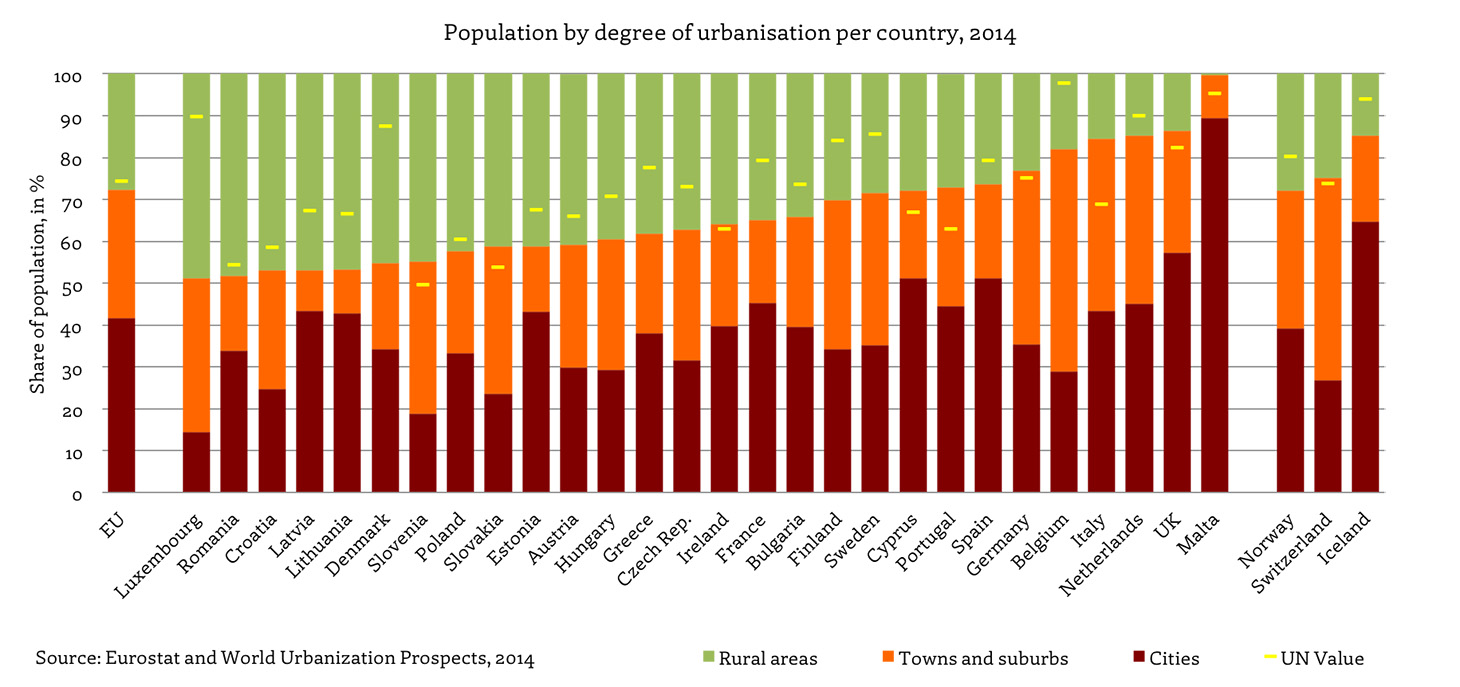

Even more insights can be drawn from a mammoth European Union study, The State of European Cities 2016: Cities leading the way to a better future. This report compares major cities with over 250,000 people in their ‘Functional Urban Areas’ in a superb series of maps and charts. Europe turns out to be less urbanised than some parts of the developing world, but has a much denser network of cities. Most people live in mid-sized cities, not capitals, and unlike the UK, European mid-sized cities do better than average.

Switzerland

Tackling inequalities

Economic success is normally measured in GDP per head, or productivity, where only London, and surprisingly Dublin, stand out as ‘very high-income regions in the British Isles. The contrasts between the English North and South are vividly shown. The EU study goes beyond the Centre for Cities in explaining economic success.

‘Several factors can boost urban productivity; human capital, the quality of the business environment, entrepreneurship, quality of institutions, market access, access to capital, costs of land and labour, as well as research and innovation.’

Significantly, the cities that stand out in terms of Life Satisfaction include Munich and Leipzig, Antwerp and Graz, and Zurich, rather than the capital cities, which may offer useful lessons for our second cities. The cities that are thought as offering ‘good housing at a reasonable price’ turn out to be Eastern Europe, or in the UK in Tyneside and Belfast. So expensive housing may be one of the prices of success!

Aspern landscape

Inclusivity is about more than affordability, and there is an interesting comparison of the degree of segregation or dissimilarity, which reflects the concentration of social housing. Here the cities in the former Soviet Bloc do best, and most capitals have worsened in the decade after 2001.

Mobility in terms of car dependence varies hugely, with the Netherlands doing best in taming the car, and Britain worst along with France. However, France is much more rural than the UK, and our authorities need to learn from cities like Vienna, where car trips fell from 40 to 27 per cent over a couple of decades, and in most cities cars are now used for less than 30 per cent of trips. In contrast, rail-based transport has greatly increased its usage in Western Europe. London and the South East stands out as having the most congested road network, perhaps because in the extensive suburbs cars are used much more. A fascinating chart shows how cities compare in access to public transport, with Bilbao, Lyon and Marseille doing notably well, while Dublin and Manchester lag behind. This shows that what matters is not just having a few iconic tram lines, but integrating the whole suburban rail network in a seamless system. The outstanding cycling cities are Groningen in the north east of the Netherlands and Copenhagen, both of which have bitter climates in winter.

Natural resources also matter, and the EU suggests measuring access to green spaces within a 10-minute walk, making use of the Copernicus Urban Atlas. As cities are denser than rural areas, they use infrastructure much more efficiently. Paris is denser than London in the first 10km but beyond that very similar. But the relationship between urban form or densities and environmental performance is not yet understood, and many small green spaces may be much better than a few larger ones. Pollution tends to increase with city size, as more trips are made.

City Shuttle Trains

The UK appears better suited to efficient public transport than much of the rest of Europe, which suggests that the declining usage of buses could be reversed. However it is in Scandinavian cities such as Malmö that the greatest progress has been made in tackling the causes of climate change. The Amsterdam Smart City initiative is notable for its 80 partners working for a low carbon city, while Manchester is praised for its University Living Lab initiative and innovation district.

Urban governance comes last, but probably is the most fundamental key to success. In Europe as a whole, local government is responsible for almost half of public investment, whereas the UK stands out for being so centralised. It is the metropolitan area that matters so that cities need to work as networks. But the UK suffers from being amongst the lowest in local autonomy, far behind the leaders such as Denmark and Germany, and falling behind even the former Soviet Bloc countries in local self-rule and local public investment relative to GDP.

Can the UK respond?

The UK is currently pursuing mergers into Combined Authorities where others are fragmenting. The average municipality in Switzerland, one of the best performing counties, has a population of 3,500 inhabitants, whereas in the UK it is around 150,000, five times the level in most of the rest of Europe. Unless ways can be found of generating fresh local sources of income, most of the UK is likely to fall even further behind. So the last report to be reviewed, PWC’s Good Growth Index, proposes an Agenda for Action that calls for ‘Proactive local leadership …to define the vision and identity for the place — what city stakeholders want the city to be famous for.’ This is surely one job where the Academy should be able to help!

Dr Nicholas Falk AoU is executive director of The URBED Trust

1. Hugo Bessis, Competing with the Continent, Centre for Cities September 2016↩

2. Peter Hall with Nicholas Falk, Good Cities Better Lives: how Europe discovered the lost art of urbanism, Routledge 2014↩