In 1951 the results of a major architectural competition were announced. The winners were three academics from Kingston School of Art who had each submitted separate entries to improve their chances. The practice they would go on to form —Chamberlin, Powell and Bon — would build their winning entry for the Golden Lane Estate – shortlisted in this year’s Urbanism Awards – and would later go on to design the Barbican. However, theirs was not the most influential entry to the competition. That belonged to a practice who were not even runners up but who were very good at getting their work into the mags. Alison and Peter Smithson were the darlings of the architectural press at the time and their big idea for Golden Lane was the street in the sky.

Much of the architectural idiocy that we have covered so far in this series relates to well-meaning policies taken too far or misapplied. However, there is another type of idiocy that comes from a reimagining of the future in a space that is part architectural and part science fiction. In 1951 we were very excited about the future. It was on display under the Dome of Discovery as part of the Festival of Britain, holding out the promise of a future free from the dirt and grime of the pre-war industrial cities. The country was emerging from post-war austerity, the Labour government had created the Welfare State and the National Health Service and the people had shown their gratitude by replacing them with the Conservatives who came to power on a wave of optimism in the election of 1951. The ‘home of the future’ on display at the festival was incompatible with the cramped terraces and tenements that characterised British cities and the damage done by wartime bombing created an opportunity to build something very different.

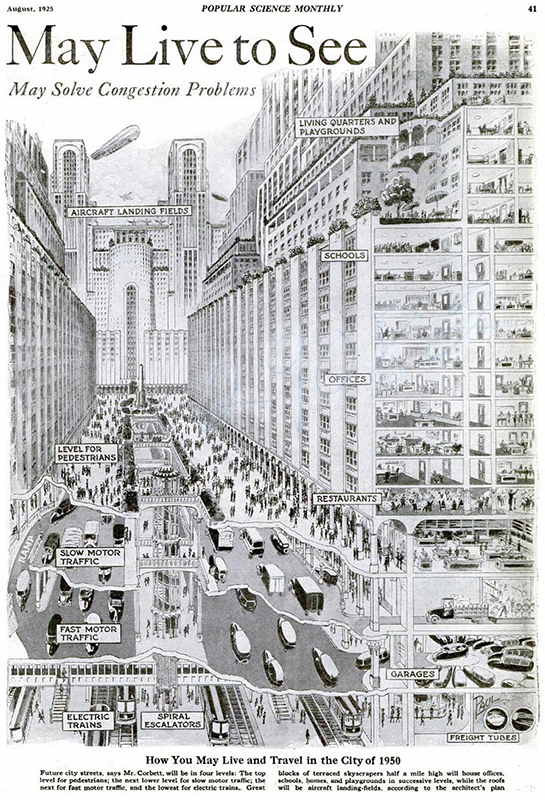

The big issue to be addressed was traffic. Even though levels of car ownership were tiny compared to those of today, people had stated to see the various functions of the street as being incompatible. There was already a long history of illustrations of the city of the future including multi-level streets. A drawing by H.W. Corbett dates from 1913 and another from Popular Science Monthly in 1925 imagines the city of 1950 with underground subways and high-speed streets. Layered above this are levels catering for deliveries and local traffic while above this are the pedestrian walkways spanning between buildings with landing strips for airships at roof level. Much later Paul Rudolph would suggest something very similar in his 1962 scheme of mega structures built over the multi-layered Manhattan Expressway. However, all of these are still fundamentally streets. The movement may be split onto multiple levels but the buildings front onto the street and the structure of the city would still have been recognisable to a 19th century urbanist.

© Popular Science Monthly

The modernists, however, had no time for such traditions. In their view the ‘corridor’ street as they called it, was no longer able to deal with the speed and volume of traffic required in the modern age. Better to create an entirely separate system of expressways and access routes free from frontage development and separated from pedestrians. The Ville Radieuse (The Radiant City) buried its roads below ground leaving the ground plain clear for open space with accommodation contained within regularly spaced towers. These towers contained internal streets, indeed Unite d’Habitation in Marseilles has a very successful street on the fifth floor with a small general store and even a café.

This may have inspired the Smithsons but in their plan for Golden Lane they took the idea much further. Their idea was essentially to lift the terraced house from the ground into the air and stack it along elevated walkways which would become ‘streets in the sky’. It was not the first time that flats had been accessed off balconies. The early Peabody blocks were designed around a courtyard lined with balconies but the blocks themselves addressed the real ground-level streets. The Smithsons envisaged that the streets in the sky would become a new circulation system for the city allowing pedestrians to move around in the fresh air and daylight far above the traffic below. For this to work the buildings would need to be linked together so that walkways and bridges connected the blocks at the upper levels. The resulting plan is the city turned inside-out. The buildings become the structuring element rather than the streets, and snake their way over the landscaped site in a way that was entirely alien to any city planning that had come before.

The Smithsons were one of those practices whose publicity of their unbuilt schemes gave them a reputation far greater than their built output. It wasn’t until 1966 that the Greater London Council gave them the chance to build their streets in the sky in a commission for Robin Hood Gardens in Poplar, east London (recently demolished to the consternation of the architectural community). However, by that time streets in the sky in the form of ‘deck access housing’ had become an accepted and widely-used typology for council housing. The first substantial scheme to be completed was Park Hill in Sheffield, designed by Jack Lynn and Ivor Smith, who acknowledged their debt to the Smithsons. They had been commissioned by John Lewis Womersley, Sheffield’s City Architect, who would go on to form Wilson and Womersley in Manchester, the practice responsible for the largest of all the deck access schemes — Hulme in Manchester.

Park Hill is now a Grade II* Listed building and is in the process of being refurbished by Urban Splash. It has the great advantage of being able to use the sloping sites so that each of the walkways is accessible from ground level. To the south it starts as a four-storey block and the roof line remains constant as the site falls away until it eventually reaches 12 storeys. There is one walkway for every three floors and they are wide enough to accommodate a milk float. Having a walkway every three floors is what makes the proportions of Park Hill so pleasing. It is achieved by use of an ingenious cross section with front doors giving access to flats below and above the walkway. The more typical arrangement, seen in Hulme, was to use two-storey maisonettes and so to have a walkway every other floor. The problem with the Park Hill model is that the walkways are lined with front doors and no windows. There is a famous picture of 1960s housewives gossiping on their doorsteps but it must have been staged because despite their name the walkways never functioned as streets.

Park Hill, Sheffield © Soreen D via Flickr

As anyone who – like the idiot – has ever lived on a deck access estate knows, they suffer from fundamental flaws that means they can never work as streets. Typically they were carved into the building so the environment consists of blank front doors on one side, a concrete ceiling and a precipitous drop on the other. There were no eyes on the street and no way of avoiding trouble coming in the other direction until you got to the next stairwell or lift. Once in the enclosed stairwell no-one at all could see you (and the smell of ammonia became over powering). They also failed the basic test of a street in that they didn’t go anywhere and generally ended in a dead end many storeys off the ground. As a result the only people who shared the walkways with their residents were the drug dealers and muggers who prayed on them. Peter Smithson came to recognise this. Interviewed in the 1990s he said: “In other places you see doors painted and pot plants outside houses, the minor arts of occupation, which keep the place alive. In Robin Hood you don’t see this because if someone were to put anything out people will break it… The week it opened, people would shit in the lifts, which is an act of social aggression”.

Streets in the sky are a sad story of what happens when architects try and dictate the way people will (or should) live. They imagine scenarios of children playing on streets in the sky while their parents gossip on doorsteps and the friendly milkman stops for a chat. It is a romanticised view even when applied to a traditional street, but for all of the artist’s impressions of happy people, the street in the sky is an illusion. Thank goodness we have put this idiocy in the past! Except of course for all of the recent high-rise apartment blocks that include ‘sky gardens’. Just as in the past the word ‘sky’ makes it cool and the CGI’s of people having happy communal barbecues in what, in realty is a windswept place is just as misleading.

The Urban Idiot