Judith Sykes © Peter Clarkson

Judith Sykes spoke at the Academy’s conference in Milton Keynes in June this year on the emergence of smart technology and its use in the management of urban places. Her perspective as a civil engineer has been broadened through a wide range of projects, planned and implemented, in the UK and overseas. Steven Bee AoU took the opportunity, on behalf of Here & Now, to meet Judith in her office in Shad Thames and explore some of the issues and ideas raised in her presentation.

Steven Bee AoU (SB): Can you tell me a little about the Useful Simple Trust (UST) and your role here?

Judith Sykes (JS): The Trust was established in 2008 as an employee-owned group of companies working across the built environment in engineering, communications, architecture and sustainability. I joined in 2003 and am a director of Expedition Engineering and Useful Projects – preparing and implementing sustainable infrastructure strategies for diverse clients. I had previously worked in water supply engineering, mainly in the Middle East, but also played key roles on the Channel Tunnel Rail Link and Heathrow Terminal 5.

Since joining the Trust I have been involved in the detailed planning and implementation of designs for a number of regeneration and urban development projects in the UK and overseas including developing the water strategy for the London Olympics. This led to work on the 2014 Brazil World Cup and 2016 Rio Olympics. The London Olympics was great experience because the sustainability brief was clear from the start and followed through. Rio was interesting because they began by trying to copy what London had done, in terms of specific solutions, rather than identify what their priorities should be, based on an understanding of cultural and climatic context. We helped them wind back and refocus on the resilience of the new infrastructure they were installing. The lack of culture of planning in Brazil made it difficult to embed sustainability measures, especially through design and build contracts. Of course, it is terribly sad, that since the games, many of those contractors have been implicated in corruption charges.

SB: You were asked to join the commission established to guide the Milton Keynes MK2050 Vision. How did that come about?

JS: I had been invited to participate in the UKTI Innovate UK Future Cities Mission to the United States where I met Chris Murray, director of Core Cities. We did some joint projects including a conference on the role of central and local government in promoting technological solutions to urban problems. He suggested to Geoff Snelson, Snelson, director of strategy and futures at the council, that I that I help the MK Commission develop the infrastructure aspects of the MK50 Vision. Like any project it is important to suspend judgment in order to understand the dynamics of the place from the inside out, and especially so in the case of MK which perhaps had a very particular external reputation.

The early stages of the commission were about

gaining insight into how the city works, informed by engagement with local communities and a series of research papers. It is clear that MK is a city much loved by those that live there.

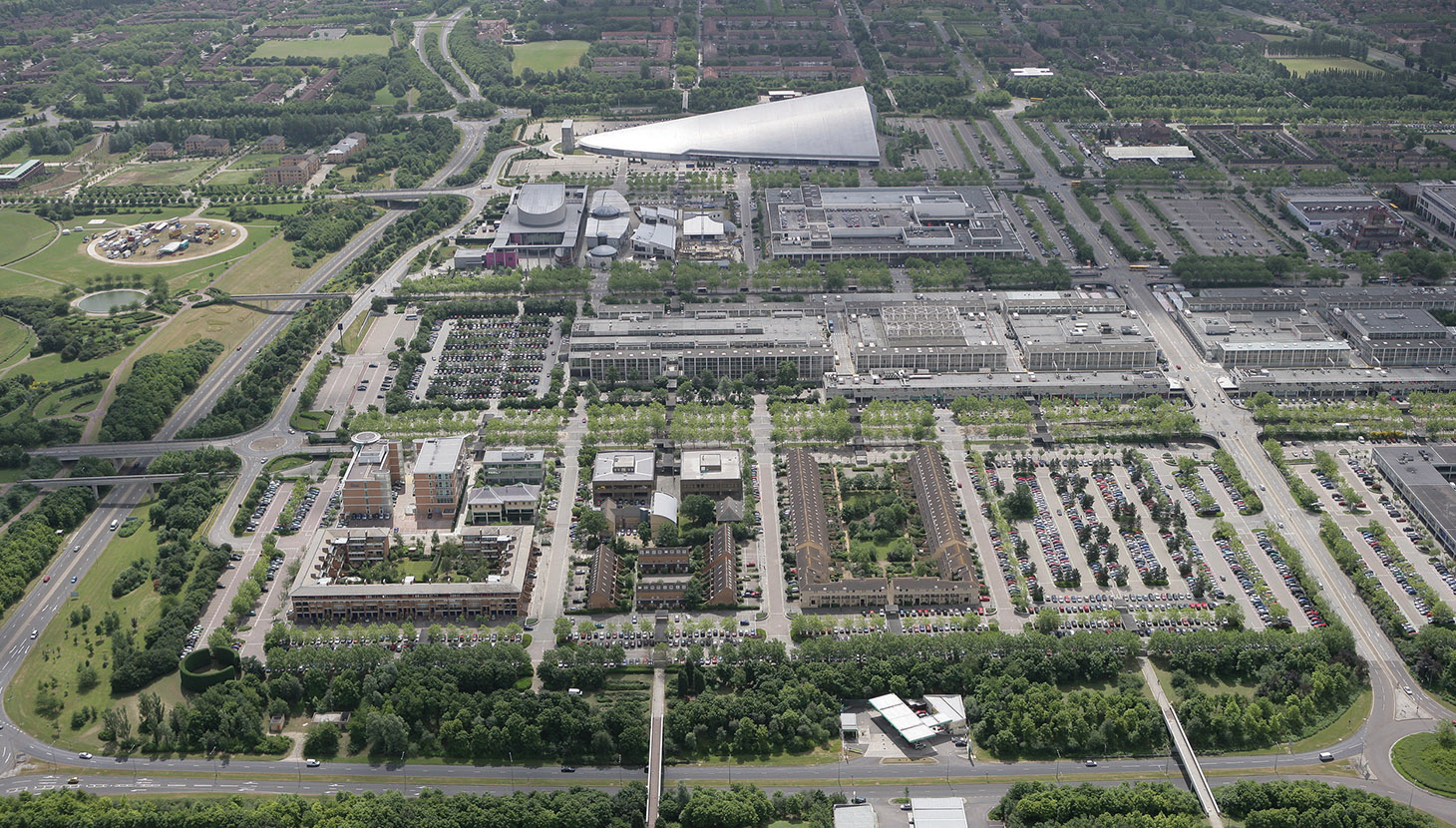

Aerial view of Milton Keynes © Destination Milton Keynes

SB: Milton Keynes is now central to the National Infrastructure Commission’s development corridor between Oxford and Cambridge. It has also become the focus through the Transport Systems Catapult of smart transport innovation. What impact are these having?

JS: Milton Keynes certainly has space and therefore capacity for growth. One of the key concerns highlighted in the commission was an over reliance on the logistics industry and a need to upskill to ensure future prosperity of MK’s citizens. At the moment the range of skills is not sufficient to attract new investment on a massive scale, but its closer association with the knowledge economies of the other two cities should add impetus to local efforts. The proposed MK Innovation University will be an important attractor in this regard.

Future investors will also be attracted by a high quality environment and cultural offering, and it is important that these are also enhanced. The lower property prices compared to its neighbouring cities and London will certainly help. A wider range of tenure types would increase its attractiveness to younger people moving in. The National Infrastructure Commission is helping to promote long term infrastructure planning, and the Cambridge-Milton Keynes-Oxford corridor would be a good demonstration project.

As for becoming a ‘smart city’, we have to be careful how we use the term. Rather like ‘sustainability’, it’s becoming a catch-all and a cliché. For me, smart initiatives must focus on individual and community health. New transport innovations are only a means to this end and walking and cycling should always be encouraged. Higher density and closer proximity of amenities will encourage and enable human-powered, and therefore free as well as healthy, journeys.

Wetland Bowl at Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park

© London 2012 Olympic Delivery Authority

SB: You talked at our Milton Keynes conference of the shortcomings of new transport technology in its infancy – autonomous vehicles, the Hyperloop, Maglev trains. What part do you see these playing in the foreseeable future?

JS: There is certainly a tendency among inventors and promoters to be seduced by technological possibilities. Elon Musk is one of the few in this field who recognises the importance of governance structures to protect us from the unintended consequences of rapid technological advances. On the US Mission with the UKTI, we received presentations from organisations like IBM and Cisco on the packages they were trying to sell to local government in the States. These weren’t being taken up because they didn’t match the needs perceived by local agencies. So technology must be appropriately orientated to city needs.

SB: You mentioned in your presentation the challenge of maintaining local distinctiveness as cities adopt smart practices. How best do you think this should be achieved?

JS: It is certainly the case that achieving higher density through high-rise development can erode the distinctiveness of older cities. I gave the example of Songdo in South Korea but there are plenty of others. High-rise is not imperative, and there are plenty of examples in Europe of higher density achieved through intensive low- and mid-rise building. Development that responds to location, topography and climate to ensure adequate daylight and sunlight, appropriate drainage and efficient heating and cooling, will tend to reflect historic patterns and forms of development. We’re working with Old Oak and Park Royal Development Corporation to build such considerations into its high-density plan. Some restriction on height and density may be appropriate, but planning restrictions can be just as detrimental to local distinctiveness, unless local planning teams are well resourced and experienced.

The way in which individuals and communities engage with technology will affect local character. We can protect distinctiveness by continually evaluating the way in which new facilities are used. Technology can actually help us visualise the impact of future patterns of activity and get feedback from communities. This will help us create places that suit the culture and environment within which they will sit. The engagement programme on the Olympic Park adopted this approach and I think the results are looking very good. Smart technology also should not just be about clinical efficiency. I am also involved in a European project looking at how technology can enhance our experience of the city working with Montpellier, Barcelona, and Genoa. Bristol also has some good examples of linking technology and cultural development through things like the Playable City.

Engagement programme on the Olympic Park © Thomas Matthews

SB: You expressed concerns about the way in which HS2 will connect with existing movement networks, with future links between connecting stations in central Birmingham as an example. How do you think this has arisen?

JS: Investment in infrastructure usually proves more successful when built on public consensus. The London Olympics proved that. The communications team for the London Olympics was very good at telling the stories about the place and what was happening on the project as it was delivered. These stimulated the public’s interest in the amazing structures and the infrastructure that would connect them. Last year’s Institution of Civil Engineers (ICE) State of the Nation report assessed the opportunities associated with the devolution of powers to local authorities. One of our conclusions was that emerging place-based solutions to upgrading infrastructure offer a better chance for successful integration with and support from communities. The top-down approach to HS2 in those early days placed emphasis on high-speed city to city connections rather than maximising local benefits by looking beyond the redline of station development. It’s too easy to blame transport engineers for being too focused, they need to be given the right brief. Lack of broad consensus on the outcomes also makes infrastructure more susceptible to Treasury cost-cutting. We are seeing a shift in focus on what happens around HS2 interchanges, but there are some missed opportunities.

SB: Finally, and going back to your perspective on Milton Keynes at 50, how well do you think the city is equipped, physically and culturally, for future growth and adaptation?

JS: This will depend to a large extent on building a political consensus that has widespread popular support. The MK50 Commission’s recommendations gained unanimous cross-party approval within the council, and was well supported by MK residents. I made the point earlier that momentum has to be maintained to see projects through. I’m pleased to see that five out of the six projects we suggested are being actively pursued. This may be a result of favourable timing in the local and national context. If there are obstacles to further growth and intensification they are likely to be cultural rather than physical. The Milton Keynes low-density lifestyle is well-embedded, and it will take some active local re-imagining for the community to accept a more intensive land use and a shift in the way people travel around the city. The iconic Milton Keynes grid plan is a huge asset in this regard and will be able to accommodate change more than others within the opportunity corridor.

Steven Bee AoU is a director of The Academy of Urbanism