Academician and Farrell Expert Panel member Robert Powell reflects on the Farrell Review and its importance for the Academy

Academician and Farrell Expert Panel member Robert Powell reflects on the Farrell Review and its importance for the Academy

The FAR Review was published on 31 March this year. I use the acronym of Farrell Architecture Review (FAR) for its metaphorical reach rather than its accuracy (if the Review says anything, it says that it’s not all about architecture).

In its scale and scope the FAR is arguably the most important gathering of serious thinking around UK placemaking issues since the Urban Task Force report of 1999. Unarguably, the invitation from Culture Minister Ed Vaizey to Sir Terry Farrell to undertake the Review was the first sign of serious interest in these issues from the Coalition government.

On both these fronts – although the significance of the second will only become clear after the election next May – the FAR represents an opportunity which I believe Academicians will want to take up. I think the question for us is not whether to engage, but how best to do so.

What choice for me then, as an Academician, but to take up the privilege and the challenge of joining Sir Terry’s expert panel for the review when invited? Its crowded launch at New London Architecture was exciting – although, I’m sure like all panelists, I had my bugbears and concerns.

I expressed them in writing to Sir Terry immediately after the first meeting of the welcomingly diverse panel in April. As ever in our sector, or confluence of sectors, agendas and languages were all banging their drums. What, I asked, did Sir Terry think was the real subject of the review? Was it architecture, built environment, design, economy, place? How should we protect ourselves from the risk that the exercise would be taken for what it clearly was not – another Rogers’ task force, wellresourced and with powerful support in government? How could we prevent it becoming all things to all people?

As director of Beam, with its arts and community development mission, I wondered why there was no word (from the department of Culture, after all) about the arts and artists, and, fundamentally, I could not see in our brief where the role of ordinary citizens is to be addressed. I suggested a ‘Challenge Paper’ approach which would produce right from the start a set of strong propositions to stimulate debate and counter the necessary but bland ‘Call for Evidence’ approach insisted on by departmental protocol. And I expressed concern that by pursuing ‘place’ via four restrictive topic areas we might lose sight of the whole, the holistic, the interconnections. Should there be a ‘fifth’ theme, the ‘Whole Picture’, as it were, or at least the identification of underlying, cross-cutting themes that would bind the Review together and resist the magnetic pull of the sector’s classic silos and interest groups?

From the start, though, there was consensus around several things.Like Sir Terry, we saw the Review as a re-beginning, not an end. The approach must be cross-disciplinary and mustn’t be allowed to fall into the single hands of any particular interest group. It needed to be seen to be independent. And it would not and realistically could not, just be about what government could or should do.

We didn’t have much time. Although the start had been delayed, the Review was still expected by the end of the year. Based, unlike the others, in the North (Wakefield), I offered to help with some of the five planned regional workshops rather than the London-based ones. With fellow panelist Victoria Thornton, director of Open City, we engaged the skills and connections of the Architecture & Built Environment Centres in Bristol, Birmingham, and Newcastle.

The schedule was close to lunacy, but everyone rose to it. All over the country, people gave of their time and ideas. Those who could not make workshops responded to the Call for Evidence. Institutions offered their premises. The small Farrells team, and in particular Max Farrell and Charlie Peel, organised, recorded, and collated the findings from workshops, meetings, debates. The sheer editing and writing achievement of the FAR, in such a short time frame, is noteworthy.

So how has the Review itself come out of the extraordinary churn of issues, personalities, pressures, agendas, and potential diversions?

As a quick reminder, the brief as described in March 2013 was ‘to engage the sector in helping the DCMS develop its thinking…to better influence and shape policy across government’. There were four themes, shown below in the order the FAR places them, with the numbers indicating the government’s original ordering:

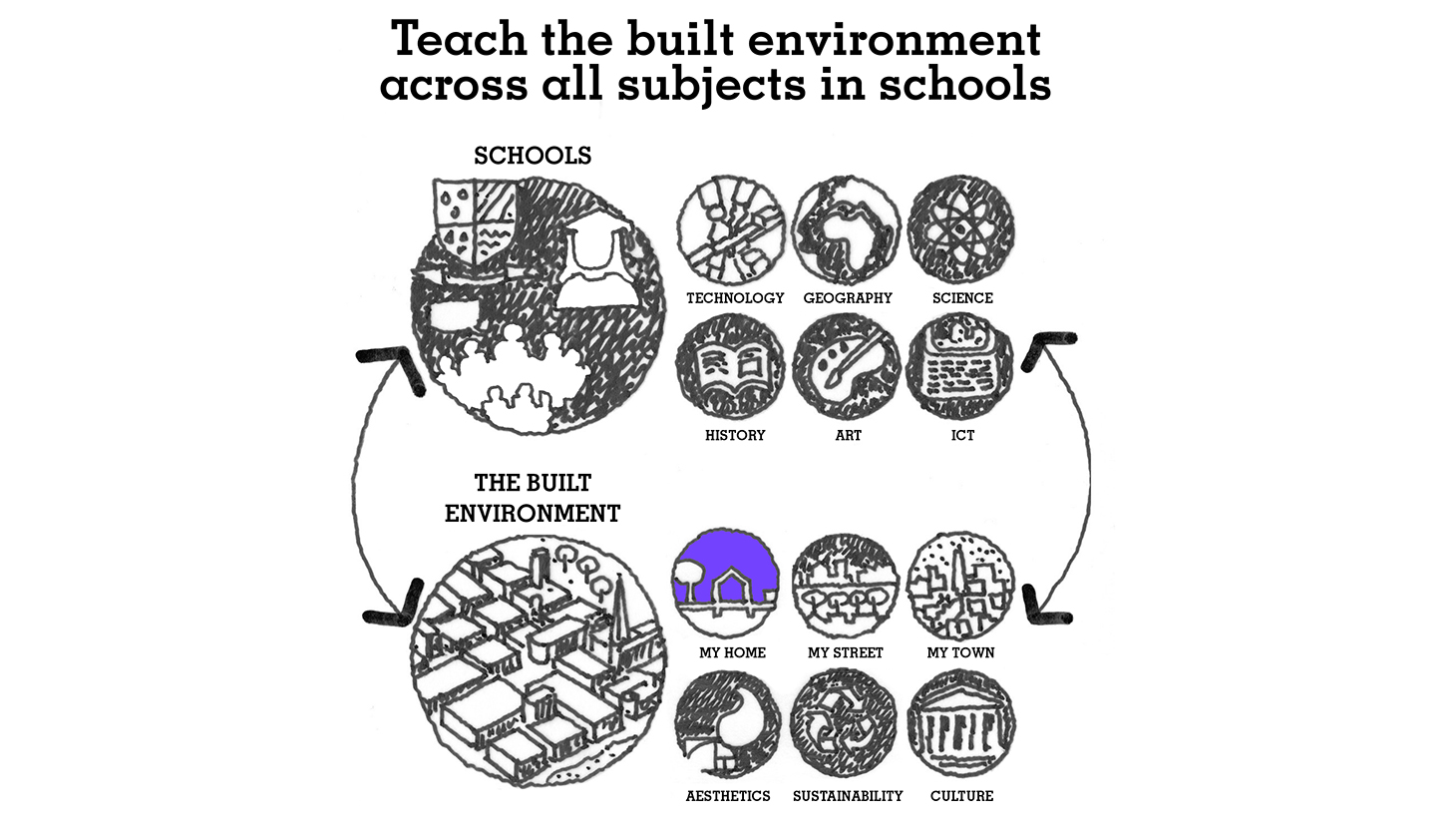

Education, Outreach & Skills (4). In reality this was always three huge topics, not one and was originally prefixed with the word ‘promoting’. Note too how professional education was left out, but is addressed in FAR. ‘The review will consider the potential contributions of built environment education to a broad and balanced education both as a cultural subject in its own right and as a way of teaching other subjects. Public outreach and skilling-up will also be considered.’

Design Quality (1): originally outlined as ‘Understanding the role for government in promoting design quality in architecture and the built environment. The review will look at lessons…nationally and internationally about the role for government. The role of built environment bodies and other organisations…and better understanding of design quality… will also be considered.’

Cultural Heritage (3): ‘The review will look at how to encourage good new architecture whilst retaining the best of the past, and the value of our historic built environment as a cultural asset and in successful place-making’.

Economic Benefits (2): ‘The economic benefits of architecture and design, and maximizing the UK’s growth potential…’

To these the FAR adds a fifth theme, Built Environment Policy and rightly resurrects it into an overarching responsibility from its original burial place in Design Quality. The resulting report, Our Future in Place, will disappoint some. Its breadth makes it seem un-radical. It does not do every issue full, or perhaps even partial, justice. It fails to locate resources. Yet the FAR is, I think, a substantial, even remarkable, achievement. The Introduction by Terry Farrell is truly engaging, deepened by his long experience. The Executive Summary is succinct, highly accessible, and made more so by its clever graphics. Its open spirit is highly untypical of similar government-inspired reviews. Its true gold lies in the body of the full report, because in it the multi-faceted research and consultation gives voice to the richness of skills, perspective and commitment of all those who took part, and demonstrates how the report’s conclusions and recommendations are rooted in the consultation.

If the FAR is not quite the battle cry or manifesto some would have wanted, it is a first essential step to recovering, for a new era, the dispersed voices and experiences of the past 15 years; a re-gathering, in one place, of the issues; a statement of what needs to be done, with some strong ideas about actions, all bound together by five cross-cutting themes.

Actually, perhaps, it is all things to all people – in the positive sense that there are opportunities in it for everyone, from ordinary citizens to professionals in the built environment, education, community and economic development, the arts. On the surface more sensible than radical, the FAR’s actual radicalism lies in its championship of the centrality of place, its capacity to involve, and its success, at least to some extent, in unifying the divisive specialist languages of the sector into a more single-minded lexicon based on a holistic view of the issues and implications embedded in the idea of ‘built environment’.

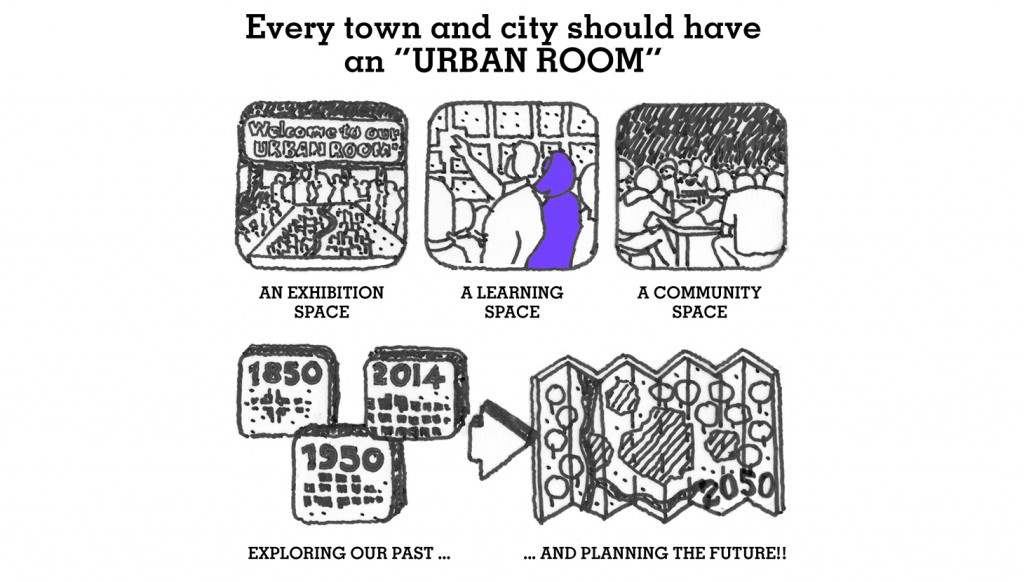

To achieve its potential, however, the FAR’s ideas of ‘P.L.A.C.E.’ (whatever words you choose to jam into the acronym) need to be further defined, argued through, maintained, and disseminated throughout the hierarchies of those responsible for the built environment and, fundamentally, to the ‘crowd’ – the people who populate it, not least the young.

The vulnerabilities of FAR lie in its lack of meaningful government support and resources, its very openness, and perhaps particularly in the vexed question of where leadership will come from to deliver an effective measure of both implementation and unity. If the FAR has cleverly managed to pull all the issues together, and created opportunities for anyone, anywhere, to pick up any one of its multiple strands and take action, then how and by whom is this inherently multifaceted territory to be kept together so that the holistic is not lost and the overall agenda broken into fragments?

This is where members of the Academy, and the Academy as a whole, can play a significant role. The eclecticism and the risks of FAR makes the AoU, with its place-based ethos and breadth of membership, ideally placed to play a truly important part in the next phase of bringing the issues into diverse but also unified life.

Let a thousand flowers bloom, or even a hundred – but let them all be in the same garden, and connected by pathways we all use.

Robert Powell AoU is director of Beam, a company dedicated to the imaginative understanding and improvement of the public realm