The uneven geography of Britain’s economy has been more than a century in the making. Paul Swinney argues that to address it, the government must learn from the mistakes made by previous policy-makers.

One of the most commonly cited factors for Britain’s decision to leave the EU is that the economic disparities across different places in the UK helped galvanise the vote for Brexit – with people living in Britain’s so called ‘left-behind places’ using the referendum as a way to kick back against the political establishment. It’s not surprising, then, that Theresa May has made tackling these divides a top priority in her first months as Prime Minister, launching a new economic and industrial committee tasked with driving growth “up and down the country, from rural areas to our great cities”.

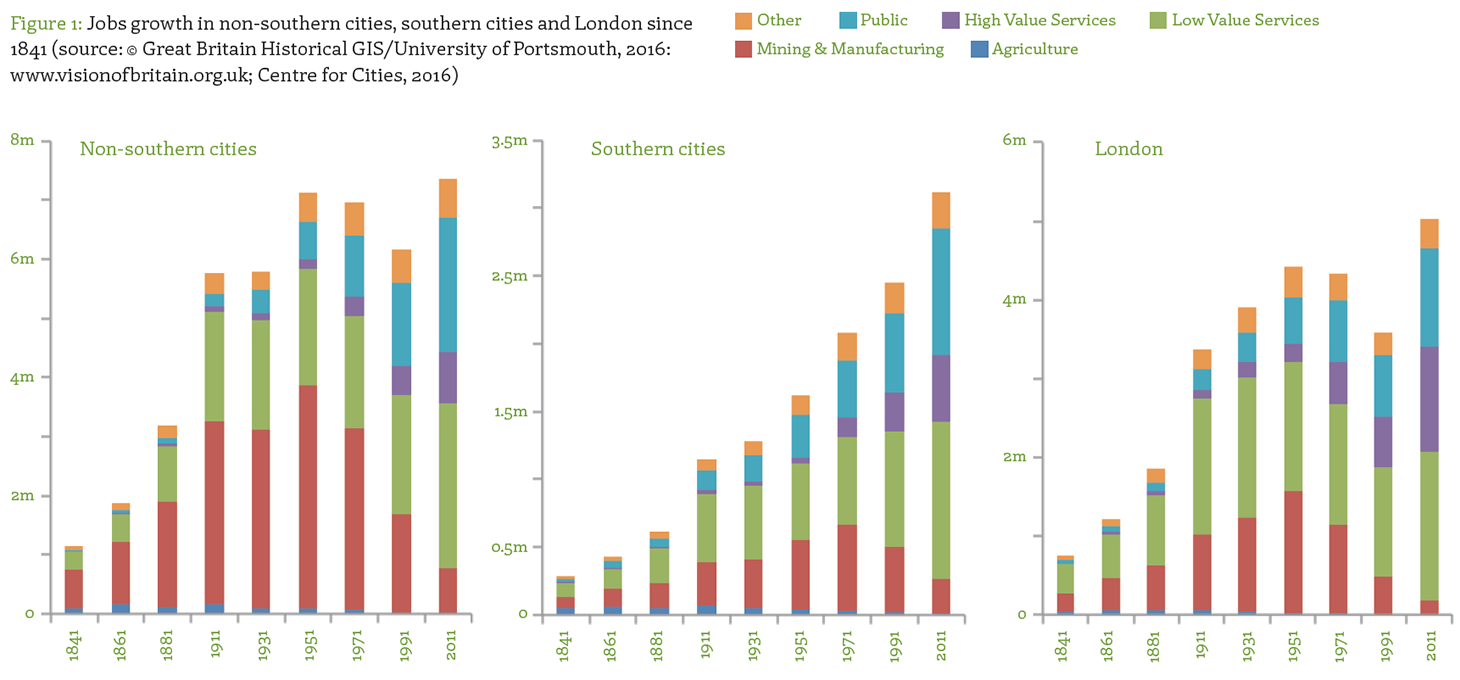

However, to understand the uneven economic development of the UK and how it can be addressed, policy-makers need to look at how Britain’s economy has changed over the past 180 years – and in particular, why some places and industries have thrived, while others have gone into decline as a result of globalisation. Figure 1 shows the growth in jobs of different parts of the UK since the first half of the nineteenth century, divided along the following categories: southern cities (excluding London), London itself, and cities elsewhere in England and Wales.

Let’s split these charts into three phases. Phase I runs from 1841 to 1951. It shows the incredible job creation seen in cities in the North, Midlands and Wales during this period, which were six times larger by the end of the period than at the start of it. This growth was driven predominantly by the expansion of mining and manufacturing, which accounted for half of the total growth over the period.

Phase II runs from 1951 to 1991. During this time, these cities went into reverse, seeing their total number of jobs decline by 14 per cent. This was a result of increasing globalisation, which opened up the manufacturing growth engine of these cities to ever greater global competition. The outcome of this increase in competition was that jobs in mining and manufacturing fell by 56 per cent. Phase III signals another shift in the economies of cities outside of the south of England, with the total number of jobs rising again in these places. This time, however, it was the growth of the public sector that hid the continued malaise of the private sector, which was 22 per cent smaller in jobs terms in 2011 than its peak sixty years earlier.

Now contrast this to the performance of southern cities, where economic growth has been uninterrupted since 1841, primarily because they have historically been less reliant on mining and manufacturing to grow their economies than cities elsewhere. As a result, they expanded more slowly up until 1951, but were not hit as hard by the decline of the two sectors after 1951. The rise of higher value services in their economies has allowed them to make ever larger contributions to the national economy in this period, as it has moved towards specialising in these activities.

London falls somewhere between these two groups. In the first two historical phases, the capital’s fortunes reflected that of cities further north – firstly enjoying strong growth, then going into reverse in the second half of the 20th century (London had 23 per cent fewer jobs in 1991 than 1951). But since the early 1990s, London has undergone an amazing turnaround, driven by high-value service businesses, which brought 1.4 million extra jobs in 20 years.

These changes across different parts of the country have been driven by globalisation, which has created both winners and losers in the UK – increasingly rewarding highly-qualified workers, but leaving poorly-educated workers more vulnerable to global competition. Urban areas that have been the winners from this process (such as those based in the south of England) have adapted to the changes in the structure of the national economies, and have been able to attract higher-skilled business investment. They now have higher average wages, higher productivity and more new businesses being created as a result.

The opposite is the case for cities elsewhere in England and Wales, many of which have struggled to adapt. They have received business investment in recent decades – when looking at absolute amounts of foreign investment received in particular, some have done very well. But the investment they have received has tended to be in lower-skilled activities, meaning that they have swapped coal mines for call centres and dockyards for distribution sheds, rather than creating higher-skilled, higher-paid employment.

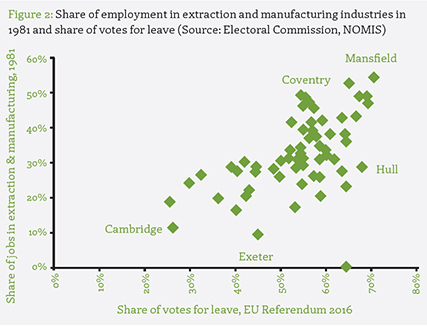

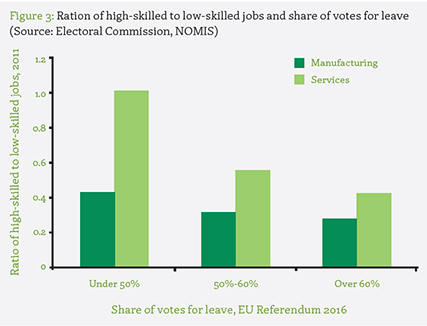

Unsurprisingly, it is those cities that have been the losers in the globalisation story that were also most likely to vote to leave. Figure 2 shows that those places that historically have had a high share of jobs in industries most vulnerable to globalisation were more likely to vote leave – there is a positive correlation between share of employment in extraction and manufacturing in 1981 and the leave vote in cities 35 years on. Meanwhile Figure 3 shows that those cities that have adapted to globalisation – they have a higher share of their jobs in high-skilled occupations today (both in services and manufacturing) – were most likely to vote to remain in the EU.

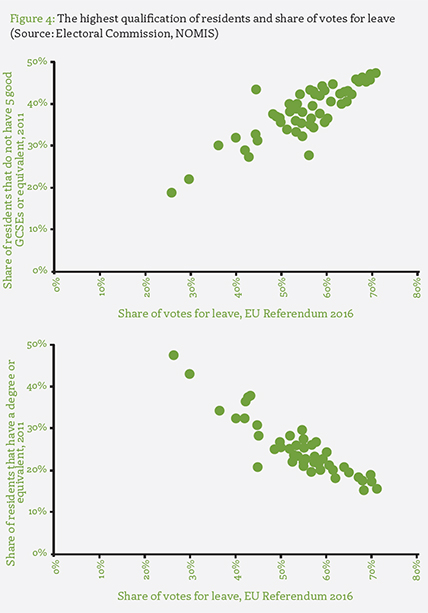

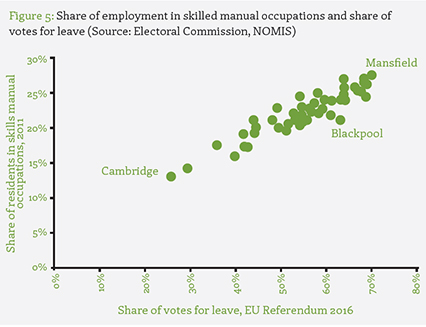

This is also reflected in the skills-levels of residents in different cities. Places with a high share of residents with degrees were much more likely to vote to remain in the EU, while those places with high shares of residents that don’t have five good GCSEs (or equivalent) were more likely to vote to leave. Meanwhile those cities with the highest share of skilled manual workers – those most vulnerable to their jobs being automated or moved offshore in the future – were also most likely to vote to leave.

This seems to support the narrative that people living in economically depressed places used the referendum to hit back at a political establishment which they feel has overlooked their interests. However, the truth is that policy-makers have not ignored the struggles of those hit hardest by globalisation – far from it. Governments of all political persuasions have been trying to address the growing north-south divide for at least 80 years, and in that time vast sums of money have been spent in struggling places – both by the UK government and more recently through EU funds – and numerous programmes and policy initiatives have been launched to tackle these problems.

Yet these interventions have not had the desired impact because they have done little to equip people and places to respond to the changes brought about by globalisation. For example, in many places there has been investment in new buildings and dual carriageways, with little assessment as to whether lack of space or congestion are the fundamental barriers to business growth in these places – or whether that money could be used more effectively on tackling other barriers to business growth.

More counterproductively, we’ve had a string of policies and rhetoric (such as the industrial interventions of the 1970s) aimed at preserving employment in declining industries, rather than helping different sectors and places to adapt to the changes in the economy. As such, policy-makers have not ignored these places, but they have failed to meaningfully tackle the root cause of their problems.

To address the economic disparities that helped drive the vote for Brexit, policy-makers must learn from the mistakes of the past. Politicians cannot hope to address the concerns of people in ‘left behind places’ by simply investing the limited funds available into ‘visible’ commitments to improve the physical infrastructure of places, when all too often building another new road or rail line alone will have little impact on the jobs and wages of the people living there.

Instead, there should be a much stronger focus on improving skills levels in places with weak economies. Industries that offer high-paid, high-skilled work, of which the UK is continuing to specialise in (but which too many weaker economies struggle to attract) require a highly-qualified workforce with intermediate and graduate level skills. Of course, skills alone will not be enough to transform the economies of struggling cities. But history tells us that failing to address these skills challenges, now almost certainly guarantees that these cities will continue to struggle in the future – our research shows that the current struggles of cities like Hull and Stoke have been at least a century in the making.

More generally, the government also needs to ensure it is building on the strengths of the national economy, by recognising and responding to the diverse roles that different places – and cities in particular – can play in generating growth. As Centre for Cities’ recent report Trading Places underlines, that means prioritising policies to support continued economic growth in major city regions, making the most of city centres and ensuring that more people from suburban and rural areas can benefit from that growth and access the jobs that cities offer. Places are not islands, and understanding the roles that they play in the context of their wider areas will be important for understanding how to help the people that live there.

If economic disenfranchisement is to end, then we have to enable people and cities to take advantage of the opportunities available in the 21st century economy. The emerging ‘place-based’ industrial strategy provides the opportunity to do this, changing the policy approach from one focussed on more shiny buildings to one focussed on tackling long-term problems. If this change in direction isn’t made, then history suggests that it will simply leave them vulnerable to the next economic downturn, whenever that may be.

Paul Swinney is principal economist at Centre for Cities.

For more information on Centre for Cities visit centreforcities.org