Walking is good for us, so cities need to be more walkable. George Weeks explains why walking is at the centre of Transport for London’s thinking and how using walkability models can make for better urban planning.

Transport for London’s Health Action Plan1 emphasises the centrality of walking to public health. This may, at first glance, seem like an error. Why should such a mundane transport mode be at the centre of public health innovation? More to the point, what is an article on public health doing in an AoU publication? “Get back to the British Medical Journal” I hear you cry.

It would be erroneous to dismiss TfL’s health pronouncements because urban design, walking and health are inextricably linked. Recent developments at University College London (UCL) have shone an unprecedented light on this relationship. This has the potential to reshape towns and cities decisively in favour of high-density, walkable urbanism.

To understand this relationship more fully, we need to step back a million years or so, to the emergence of Homo sapiens. The evolution of human physiology reflects the conditions of a hunter-gatherer existence. Our bodies are designed to expend large amounts of energy in pursuit of food. For 99 per cent of human history, this was inherent to our existence. Even the invention of farming in about 10,000BC did little to alter this. It has required the post-industrial society to bring humanity to a new (unprecedented) sedentary state. Since the 1970s, medical geographers have referred to the epidemiological transition of public health. It is worth providing some more detail on this.

An age of pestilence and famine accounted for the vast majority of human history. With the industrial revolution came the age of receding pandemics, generally associated with overcrowding and widespread infectious diseases. Following improvements to sanitation and urban planning, this has (at least in OECD countries2) given way to the Age of Degenerative and Man-Made Diseases where lifestyle, broadly speaking, has the greatest modifiable bearing on health.

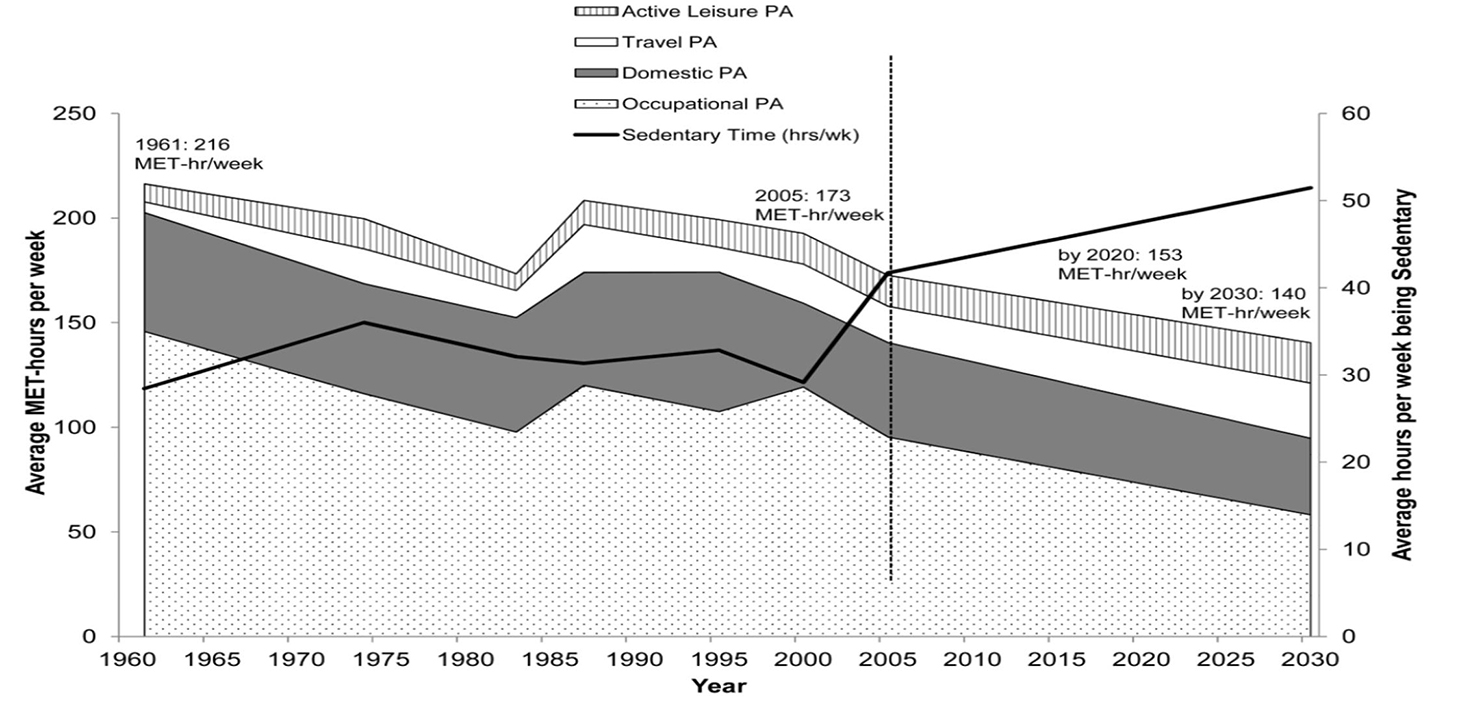

In contrast to our hunting-and-gathering forebears, inactivity (i.e. less than 30 minutes moderate exercise per week) is the biggest cause of preventable death in the UK across the population. While smoking causes a similar number of annual deaths, only about 20 per cent of UK adults smoke and this rate is falling. By contrast, the majority of adults in the UK do not meet the minimum threshold for activity (150 minutes moderate activity per week) and it is a worsening trend (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Ng SW & Popkin BM (2012). Time use and physical activity: a shift away from movement across the globe. Obesity Reviews 13(8): 659-680

Dr Joanna Manson of Harvard Medical School states: “Despite all the technological advances in modern medicine, regular physical activity is as close as we’ve come to a magic bullet for good health.” With such an endorsement, it is clearly in everyone’s interests to exercise regularly. So where does urban design come in? Before we go any further, an important distinction has to be made. Broadly speaking, there are two types of physical activity:

• Recreational activity: playing a sport, climbing a mountain, going kayaking; all of these are recreational activities. People choose to do them for their own enjoyment.

• Utilitarian activity: this occurs as a result of some other activity, such as walking to a railway station or cycling to work that would be undertaken anyway.

This distinction is crucial, explains TfL and Greater London Authority public health specialist Lucy Saunders. Out of any given population, we see a drop-off in recreational activity as people get older. This is largely due to the necessity of completing other tasks in former ‘leisure’ time, such as childcare, commuting, etc. No amount of sports ‘promotion’ will alter the number of hours in a day. For all its virtue, sport only brings benefits to the people who have the time, money and willingness to play it.

Public health, like any public policy, should aim to deliver population-wide benefits to all of society, based upon objective analysis of all available evidence. The overall aims of public health policy are as follows:

• Reduce health inequalities

• Improve overall health levels

TfL’s Health Action Plan3 has identified the areas in which London’s transport system has an impact on public health. The most significant of these is active travel. It is very valuable in public health terms because of its population-wide impact and because (unlike sport) people stick to it daily, for their entire lives. Everyone needs to undertake utilitarian trips as part of their day-to-day existence.

People are more likely to travel via active means (i.e. by foot or bicycle for part or all of the trip) if the environment is optimised for walking and cycling. At present, about a quarter of adult Londoners meet all their activity needs solely through walking and cycling. This could potentially increase to more than two-thirds if the shortest motorised trips were switched to walking and cycling (Fig 2).

Fig 2. The lower set of bars show the percentage of adults in London who currently meet their physical activity needs through walking and cycling. The higher set shows the percentaage that could achieve this if all walkable/ bikeable journeys were made by active modes

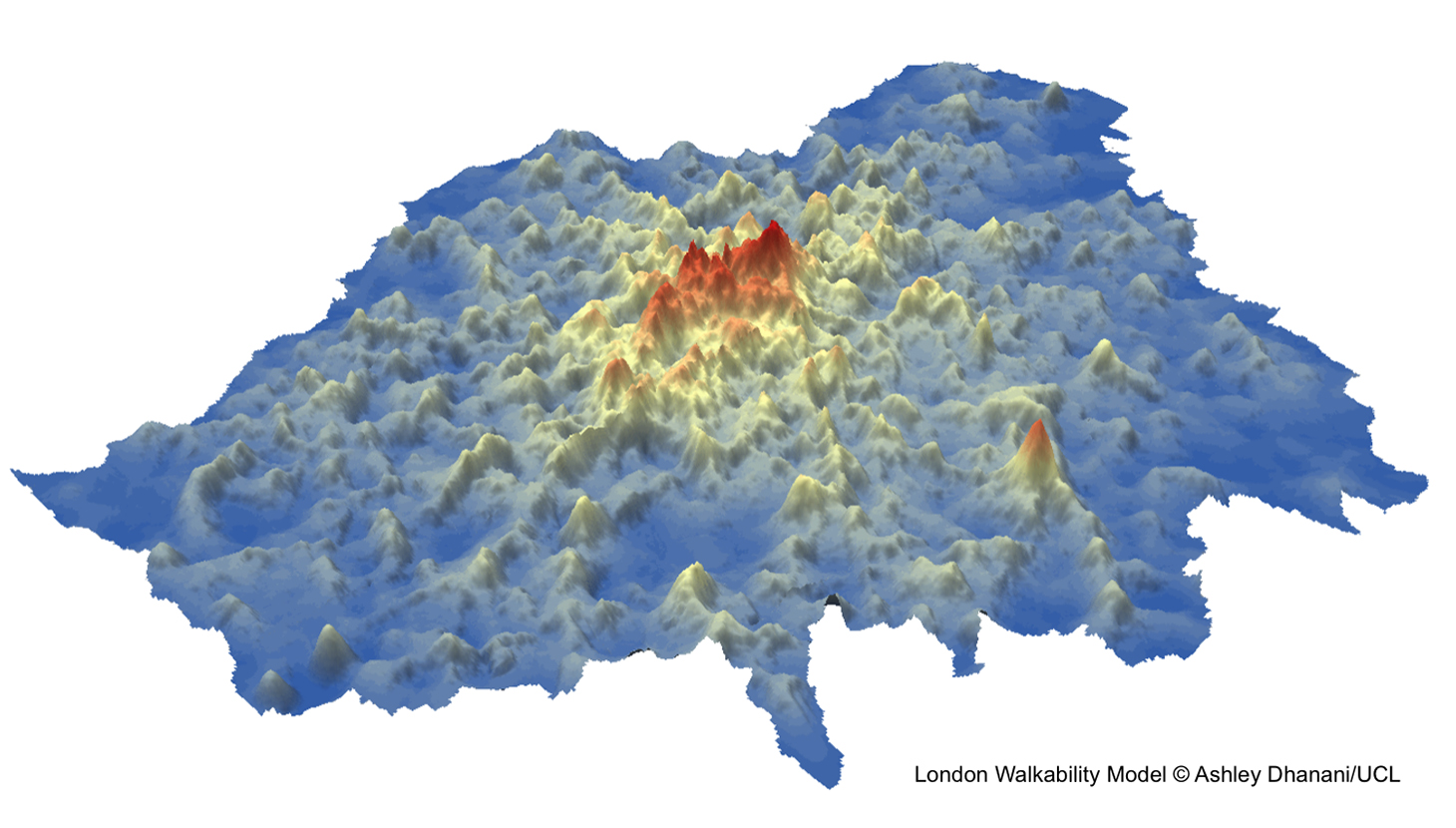

In short, the more a city can be designed to prioritise walking and cycling, ceteris paribus, the healthier its population will be. The question then becomes, what does ‘walkable’ look like? And can it be measured objectively? Both of these questions can be answered via the London Walkability Model, developed by Dr Ashley Dhanani at the Space Syntax Laboratory, University College London4.

The London Walkability Model (LWM) is a sophisticated analytical tool that uses approximately 9 million data objects to model how conducive the environment is to pedestrian activity across the capital. This goes some way towards putting walkability on an equal footing with traffic engineering, which has traditionally been backed up with enormous quantitative models. This has implications for policy.

The LWM has been developed from earlier work in North America. With its complicated street network and generally high walkability5, London requires a particular approach to measuring its walkability. The LWM uses the following four components:

i. Land use diversity

ii. Public transport accessibility

iii. Street network accessibility (space syntax configuration)

iv. Residential density

When these are combined, a 3D map is generated, reminiscent of a relief map of the Himalayas. The higher the peak, the higher the level of walkability.

When tested against TfL’s Pedestrian Dataset (obtained from six years of London Travel Demand Survey (LTDS) data), there was a significant correlation between the walkability level as measured by the LWM Index and the reported walking levels (Fig 3.).

Of the four factors that make up the Walkability Index, the two most important are public transport and street network structure, as measured by space syntax analysis. If a place possesses high-quality public transport, well-connected streets and (importantly) reasons to go there, walking levels will increase. Thus we see an objective set of ingredients for walkability.

The LWM is a tool to aid decision-making. Here are some examples:

1) It produces London-wide predictions for walking levels. This data can be compared with empirical observations to identify opportunity areas where there are lower or higher levels of walking than would be predicted by the model. An urban designer can then identify appropriate interventions.

2) For boroughs, the Walkability Model can contribute to sub-regional plans. It can identify the peak areas for walkability for each borough, and identify where the greatest disparities between predicted and actual walking levels occur. This can then feed into joined-up strategies for increasing the levels of walking in the borough and allow interventions on a targeted basis.

3) It can be used to estimate the effects of public transport investment, such as Crossrail or the 24-hour Tube on an area’s likely change in walking activity.

4) It can be used for planning active transport networks (both walking and cycling) that work with the grain of the city’s streets, and provide insight into the optimal routes that would be potentially most useful and used.

On a broader level, emphasises Dhanani, the LWM shows that a multidisciplinary approach to policymaking is vital. This reflects The Academy of Urbanism’s emphasis on multidisciplinarianism for the delivery of successful urban places. There is simply no way that a single point of view/approach can encompass all the pertinent issues. Public policy practitioners need to engage outside their immediate professional spheres. Transport and health professionals need to collaborate and understand how each other works. TfL’s Health Action Plan is a good example of this; more examples are needed.

It is important to remember that the LWN is a model. It is not an oracle. It is a starting point for a site visit by a trained professional with a specific set of objectives. Dhanani also emphasises the importance of site visits and understanding local issues. One important determinant of pedestrian movement in a street is the amount of motor traffic; an increase in a street’s walkability may depend on there being fewer cars6.

To conclude, we have seen that public policy should aim to bring about population-wide benefits. Those arising from regular physical activity are substantial. Recent advances have allowed us to show robustly that the walkable environment correlates with people’s propensity to walk.

It is therefore possible to show objectively that the healthiest urban form is one with high residential density, a well-connected street network, a rich mix of land uses and high quality public transport. All of these characteristics contribute decisively to the richness of the urban fabric; they also reflect much of the AoU’s Manifesto. This in turn reflects the multidisciplinary approach that has to underpin successful city-making. In direct contrast to the superficial (and highly flawed) rationalism of the likes of Le Corbusier, this is a truly objective approach to urban design and planning.

This article was written by George Weeks, Urban Designer at TfL and Young Urbanist, assisted by Dr Ashley Dhanani, Research Associate at the Space Syntax Laboratory, Bartlett School of Architecture, UCL, and Lucy Saunders, a Consultant in Public Health at the Greater London Authority and TfL.

1. [tfl.gov.uk/cdn/static/cms/documents/improving-the-health-of-londoners-transport-action-plan.pdf]↩

2. [Urban Sprawl and Public Health: Designing , Planning and Building for Healthy Communities, Howard Frumkin, Lawrence Frank, Richard J. Jackson; (2004) Island Press]↩

3. [tfl.gov.uk/cdn/static/cms/documents/improving-the-health-of-londoners-transport-action-plan.pdf]↩

4. [This work forms part of the Street Mobility and Network Accessibility research project funded by the UK Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council (EPSRC)]↩

5. [The contrast between walkable and non-walkable environments is much higher in the USA than in Europe. For an excellent introduction to this topic, read The Geography of Nowhere: Rise and Decline of America’s Man-made Landscape; J.H. Kunstler (1993)]↩

6. [See also Healthy Impact of Cars in London (GLA, 2015) london.gov.uk/sites/default/files/Health_Impact_of_Cars_in_London-Sept_2015_Final.pdf]↩

How does this tool measure accessibility?

I’m not so sure of the author’s claim that we had famine for most of human history. While it has occurred regularly since the advent of agriculture, it’s my understanding that before that time populations tended to live only in areas where food was available from the natural surroundings, so viability did not depend on the success of crops.