In July, six design teams met in Toronto, Canada, for the final round of an international competition to examine urban movement around a proposed new light rail transit (LRT) route in a north-eastern suburb of the city. The brief was to investigate how this new transport infrastructure could interweave with existing smaller-scale pedestrian networks to improve quality of life. Chris Sharpe AoU describes the approach of one of the finalists – a multi-disciplinary team from the UK led by Matthew Springett Associates.

Middle City Passages Toronto was a two-stage competition run by Metrolinx (the transportation authority for Greater Toronto) and the Daniels Faculty of Architecture, Landscape and Design at the University of Toronto. It formed part of a wider programme co-ordinated by the Institut pour la Ville en Mouvement looking at the concept of urban passages as connections between two places, but which can also become places in their own right.

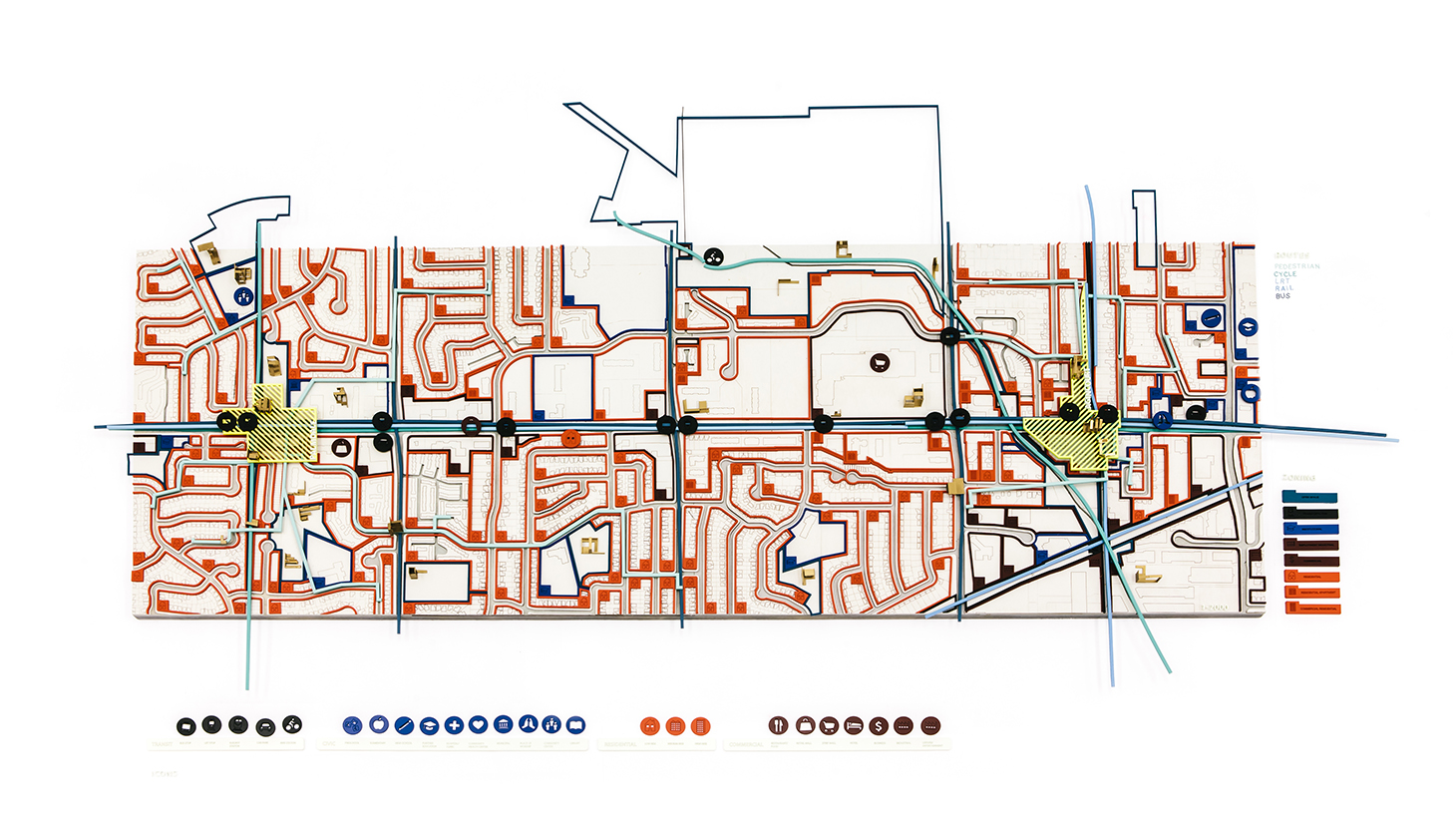

The competition brief looked at two sites along the line of a proposed new surface LRT route along Sheppard Avenue East. The sites are Agincourt and Palmdale, both planned to become LRT stations.

Sheppard Avenue East itself is a major route in the northern suburbs of the city, and at the moment is a car- dominated dual carriageway. The road has been identified by the city as a route in transition, and recent development proposals have shown an ambition to create an urban frontage along the street and transform it into a multi-role urban street.

Agincourt is a relatively old community which grew in the 19th century before being enveloped by Toronto from the mid-20th century. Today, there is a rail station which is part of the GO Transit network of commuter trains, and so the LRT station would serve as an important interchange with that network. The character of the area is incoherent – a mixture of high-rise commercial and residential blocks, car parks and shopping malls.

Palmdale does not have the same historic identity as Agincourt, and the LRT stop is named after the adjacent Palmdale Drive. This is a more typical condition along the LRT route with a simple stop serving communities on either side of the road. The site is characterised by a mixture of commercial developments and high-rise residential blocks set well back from the road and surrounded by car parks. Nearby developments of low-rise detached houses turn their back on the road and are reached through cul-de-sacs and narrow passages.

Before responding architecturally to the brief, our approach was first to engage with the communities in both sites in order to gain a better understanding of the human experience of people living and working in, and passing through the sites.

On Friday, 3 July, our team staged events at several locations using techniques such as creative stringscapes, (responsible) seed bombing raids and picnics in the park. We met with a large number of people who were proud of their neighbourhood, generous with their time and insights, and who passed on to us a great deal of knowledge.

In the short time available, our aim was not to create a set-piece masterplan, but to suggest a process where this intelligence from the community could be combined with our own architectural and landscape response in a way that supported and improved the results of the city’s investment.

In this intensive one-day process, we learnt about how people use the spaces around the road and the different and unexpected patterns of movement and waiting around the station and its car parks. Many people expressed a preference for a subway over a surface LRT, which has been an ongoing debate in the city.

Strategy

The strategy proposed for each of the sites was a three-part process – short-term, mid-term and long-term. In the short-term, small-scale interventions such as pop-up events would be staged. These would produce information about the needs and requirements of residents and also give residents an opportunity to engage with the design of their environment.

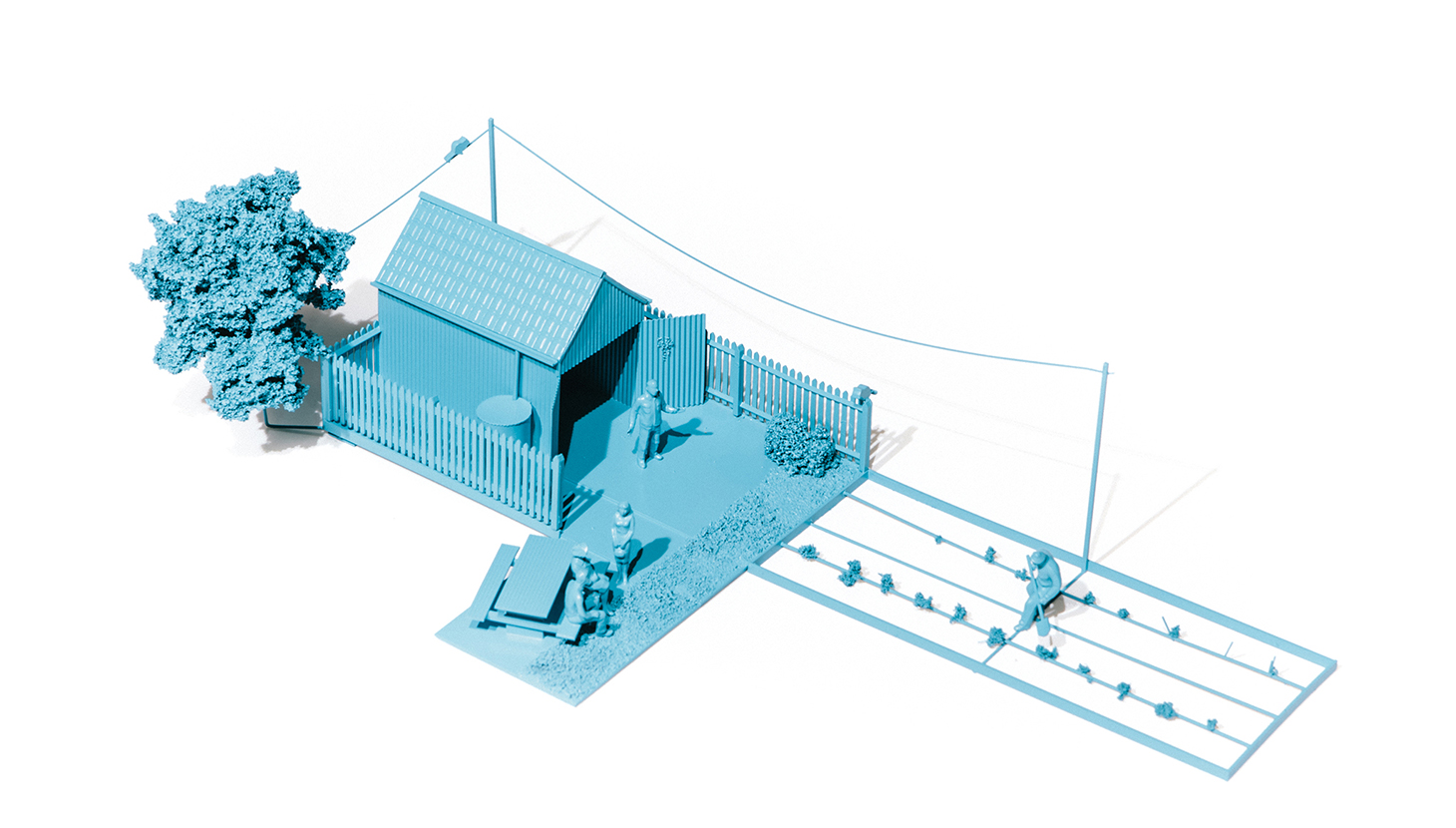

Secondly, in the mid-term, installations such as a theatre stage, allotments and nature hides would be developed to promote greater connections with the natural environment, improve new walking and cycling routes, and provide some compensation for the disruption caused during the construction of the LRT.

In the long-term, the overall masterplans for each site will be influenced by the engagement and design processes.

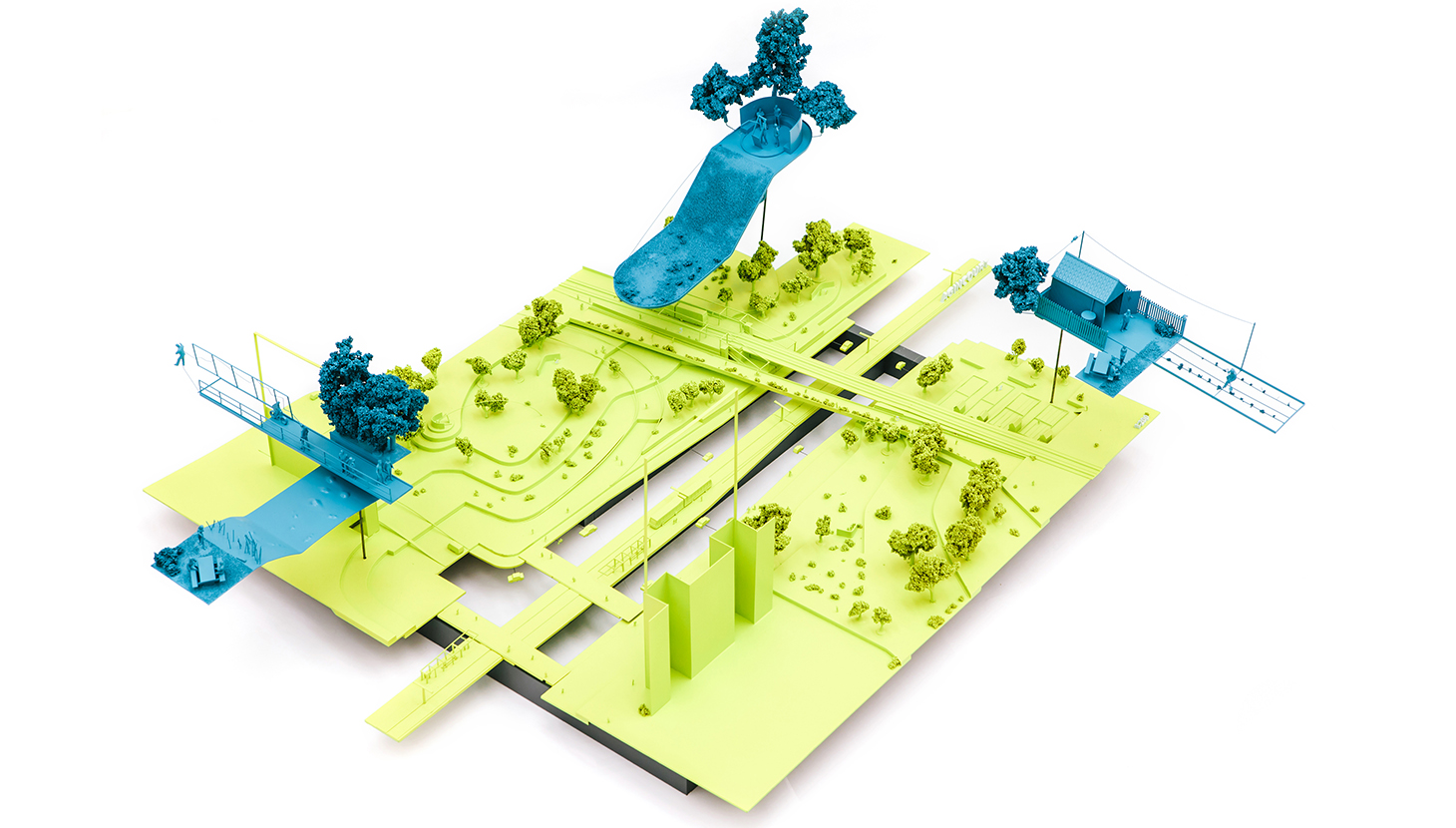

In order to demonstrate how the community engagement process could inform the design, we proposed simple, continuous landscapes of public space at both sites into which we could incorporate small, human-scale, cost-effective and community-inspired architectural interventions. These places, or ‘moments’ as we described them, would act as focal points and meeting places, defining new routes and reinforcing existing routes through the area as well as energising specific places.

At both sites, we wanted to support the ambition to transform the road from a car-dominated arterial road into a more attractive urban space which served all road users. We also wanted to reinforce connections with the natural environment – particularly at Agincourt where we envisaged a ‘green interchange’ that would link to the Highland Creek and the wider strategic network of ravines, hydroelectric power line corridors and other green spaces in the city.

Interchanges are traditionally major architectural interventions and we anticipated that the immediate surroundings to the Agincourt site would attract significant development in the coming years. However, at the heart of this site, where people would have to spend time and wait for trains or pickups, we proposed a new type of green interchange to provide a connection to nature.

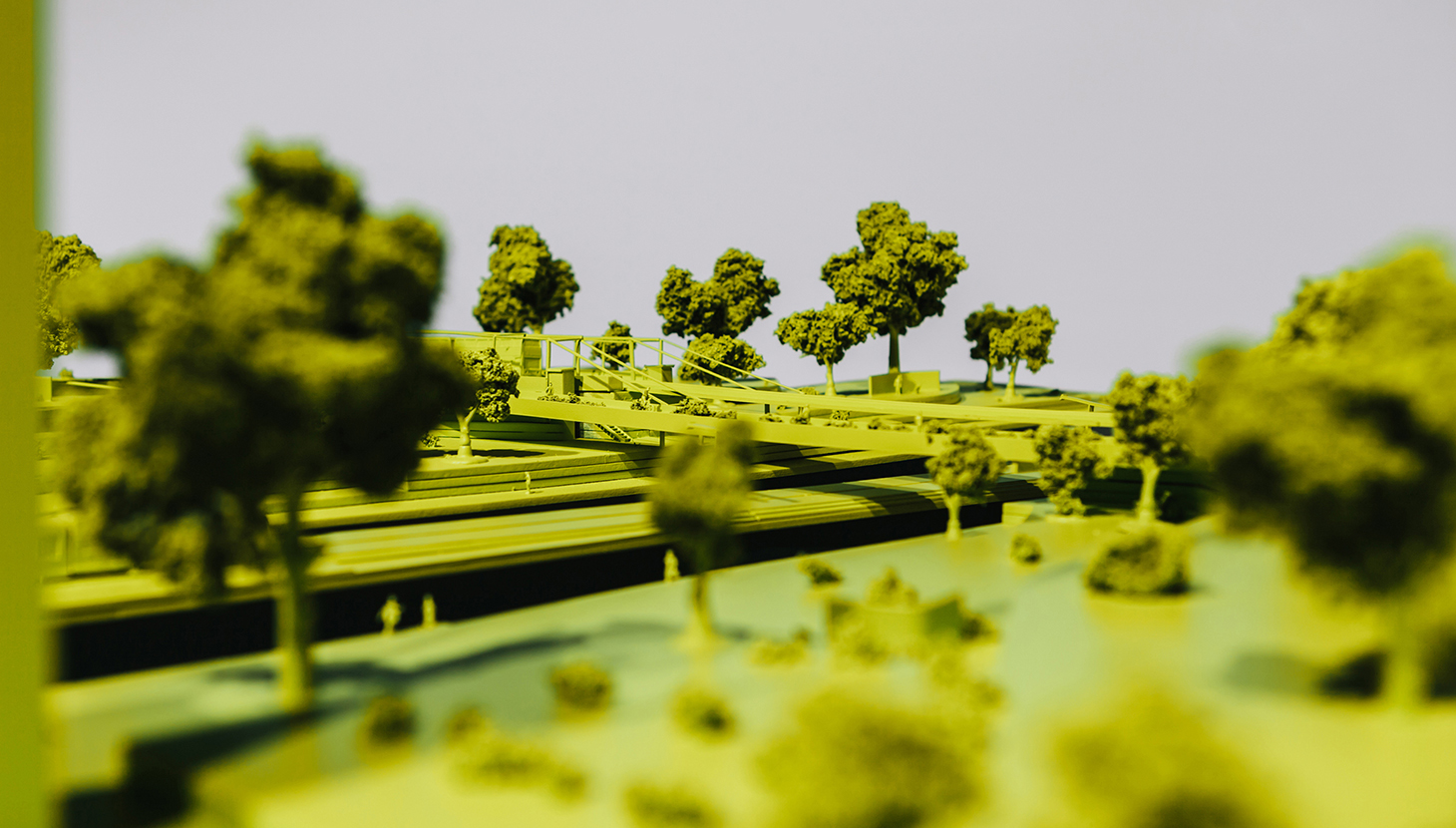

Sheppard Avenue was recently sunk into an underpass under the GO railway line to ensure that the LRT would not conflict with the train – we proposed to cut back the retaining walls to create a sloping green landscape that would rise up from the road and create a theatrical quality to the space. A park on a new landform will be created to the north of the road. Community-led interventions at this site would include allotment gardens on the slopes, a pop-up winter café near the station and lightweight cycle path structures and hides along the Highland Creek itself.

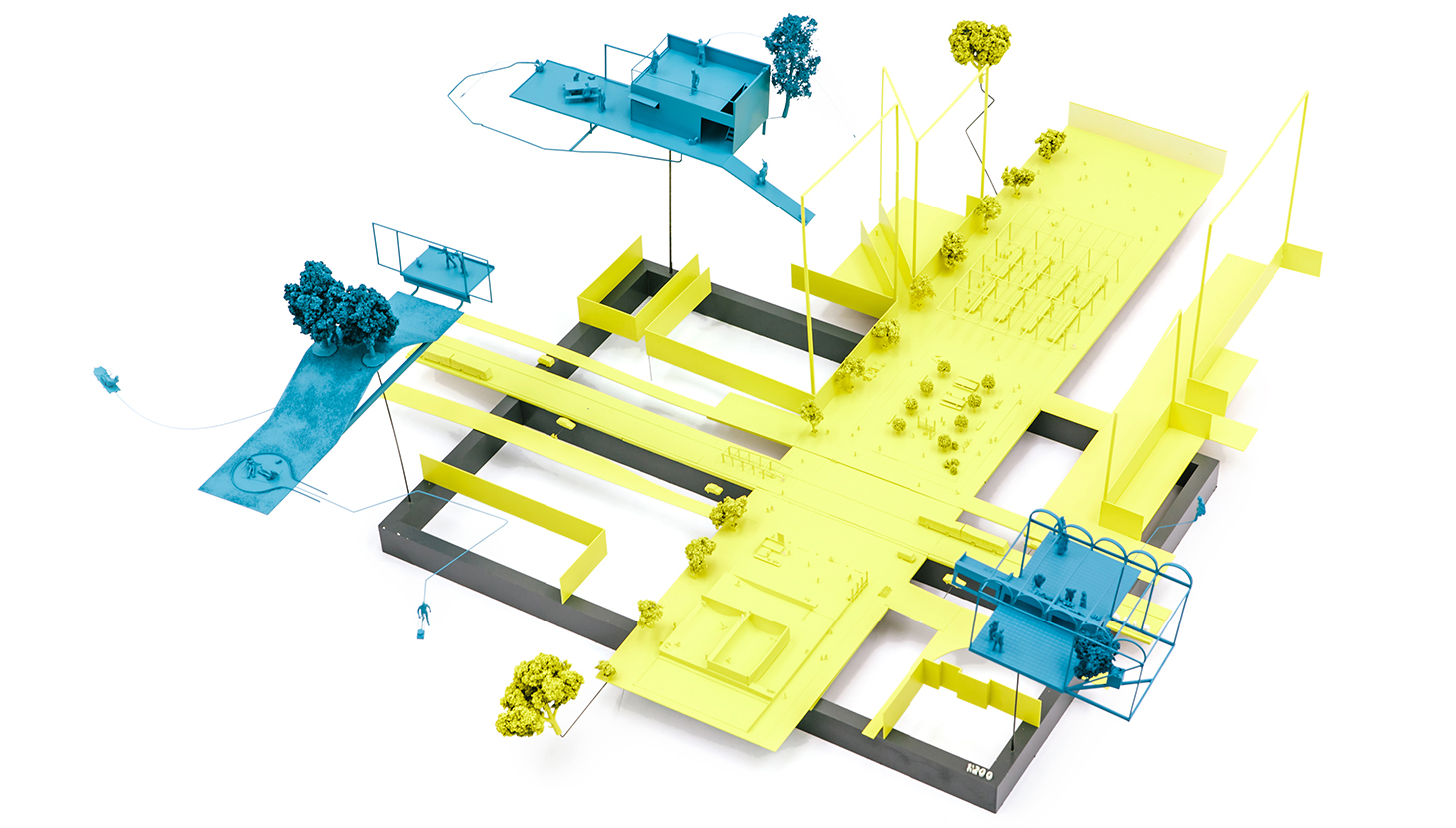

On the other site at Palmdale, the LRT proposals have already attracted large-scale development proposals along the north side of the road, which will completely transform the area in the coming years.

As a framework for the community-led interventions, we proposed a long continuous public space that crosses Sheppard Avenue, improving connectivity across the road and anticipating large-scale development around its perimeter. The interventions would include an outdoor stage in the park to the south, a leisure area for young people south of the road, an open garden and all-year-round market square to the north, and a nature hide/fishing hut in the green space to the north of the site.

As development will likely happen in stages over time, we also proposed a system for marking future sites with a line of poplar trees and creating a wild grassed area which could be used by the community in the period before development starts.

What lessons for practitioners? The importance of movement to the success or failure of cities has long been recognised and many of the concepts that emerged from the competition – improving the quality of movement routes through architectural interventions – will be very familiar in some form.

One interesting aspect of the competition was the workshop format itself. Instead of asking for final entries to be sent in by post or email, the organisers invited the finalists to Toronto and staged a workshop over several days. This ensured that all participants could visit and explore the site in greater depth, but also gave the transportation agency Metrolinx, as an end client of the process, the opportunity to meet and explore ideas with several smaller design-led practices who may not normally become involved with infrastructure projects of this scale.

Secondly, while most teams created digital models and presented them on screen, the MSA team built a set of large physical models to describe ideas and to analyse the wider urban context. This was interesting as it demonstrated how powerful physical models can still be in drawing people in and stimulating constructive debate, and how technologies such as 3D printers and laser cutters allow high-quality models to be created very quickly. At events, these models can remain in place, engaging with people and sparking conversations long after screens and projectors are turned off.

Lastly, the process of community engagement and the history of the LRT proposals was a useful reminder of the importance of politics in improving the quality of design in cities. For something good to get built, there has to be a good design, but there also needs to be people engaged in politics who can persuade everyone of the importance of that design.

Chris Sharpe AoU is a software consultant at Holistic City. For more information on this project, visit: passages-ivm.com/en/demonstrations