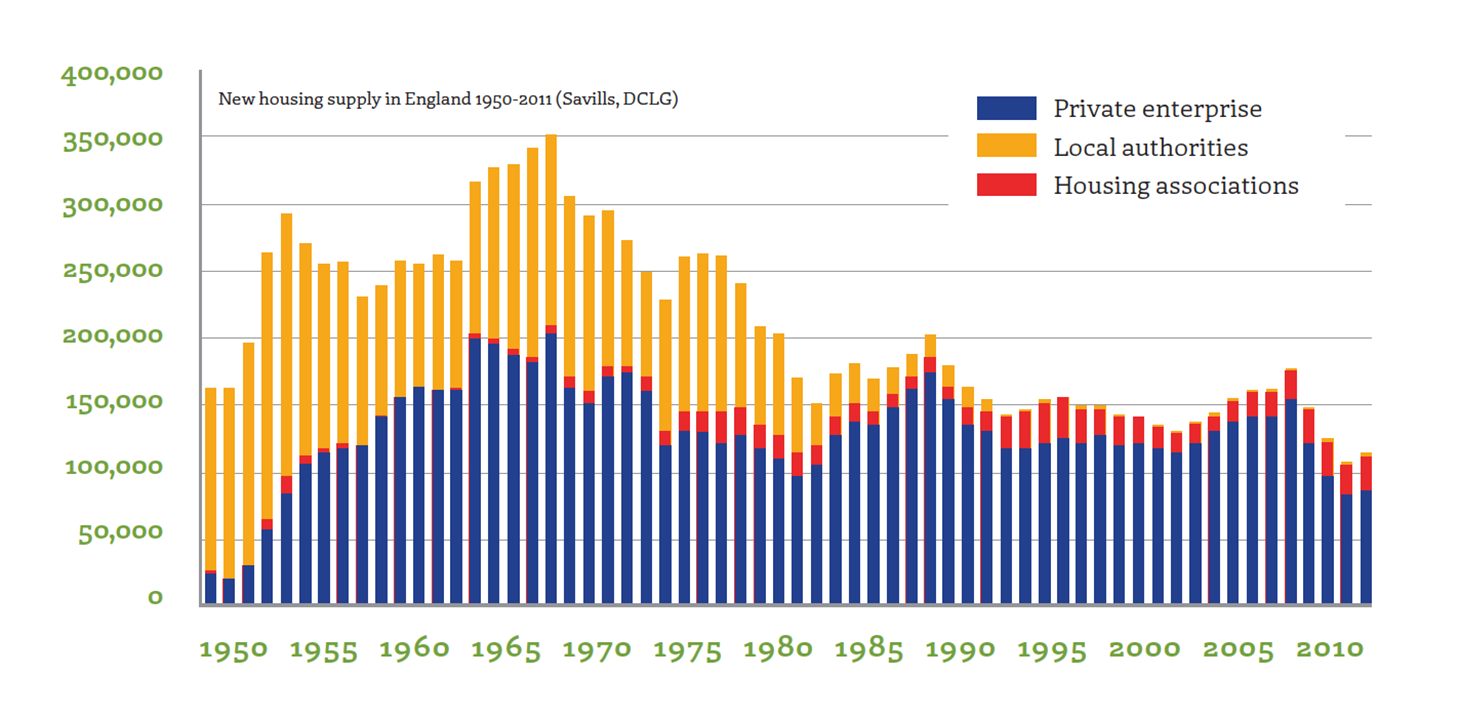

The housing crisis in the UK is deep-rooted, extensively documented, and well known by just about everyone – not least the many of us experiencing the effects. The crisis has been growing at an alarming pace over three decades in each year of which housing supply has seriously undershot demand.

Whether it is reports from the Chartered Institute of Housing, the Office of National Statistics or any of a host of sector experts the impact messages could not be clearer: from key workers being priced out of both market and rented accommodation anywhere near their place of work, to housing waiting lists exceeding life expectancies in the capital, to accelerating housing costs stripping out billions in potential consumer spend that could be stimulating the real economy.

This is a structural failure so serious that it’s impacting not just the whole economy, but also our fundamental quality of life. So why are politicians and the government sticking their collective heads in the sand?

In the Thatcherite vision from the 1980s, with its brave new world of Right to Buy council homes, Jo Public should by now be comfortably ensconced in a home-owning democracy. And, with an effective block on councils building new homes, a raft of private developers – volume, specialist and small-scale builders – should be competing to offer us reasonably priced homes. However, this simply has not happened.

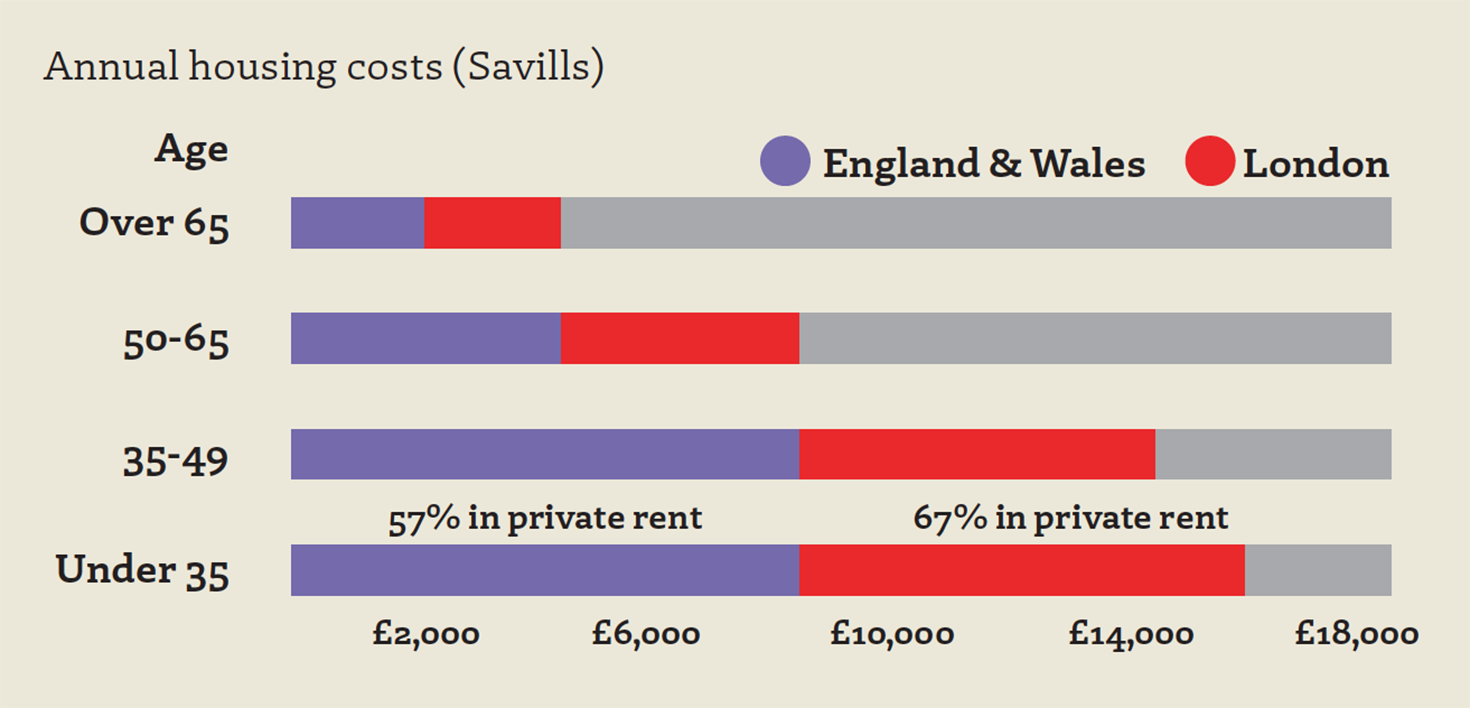

In fact, the year-on-year undersupply of new housing has had the dual effect of grossly boosting land and house prices whilst significantly growing the rented market and rent inflation, with myriad demographic, social and economic consequences. This is further compounded by the consequences of the government’s other home-owning policies, principal of which is the aforementioned Right to Buy, under which almost 40% of houses sold off with a generous discount find themselves on the private rental market1. This has given birth to ‘Generation Rent’, the effects of which are only set to continue. PricewaterhouseCooper estimates that two-thirds of those in the 25-to-34 age group will occupy this sector by 2025. Meanwhile, the biggest losers in the equation will be those who require most assistance: the Office for National Statistics calculates an expansion of the rent-to-income ratio of over 30%, from a base line of 10% in 1983 to 25% in 2014 and rising. Put simply, wages for lower income groups have fallen as accommodation costs have gone up.

The term ‘affordable’ housing has acquired an Orwellian mantle as in London alone the waiting lists for social housing in the absence of real affordability is around 350,000, extending to 1.2 million across England. At the same time, developers from China, Singapore, Malaysia and Qatar have permission to build more than 33,000 homes that are distinctly unaffordable to the average worker.

The little that’s being done to combat the growing crisis is not enough and in most cases, a diversion to meaningful change. Successive administrations have combined marginal changes to development planning with unproductive subsidy of homelessness, low pay, inflated rents, mortgages and private sector landlords – all at an annual cost to the tax payer running into the billions2.

The recent policy initiative that extends permitted development rights to convert office to residential use is actually taking capacity out of employment allocation with no chance of switching back. This is a policy destined to create problems for the future balancing of jobs with local housing. In London some 1 million square metres has already been lost to office employment use, equal to 25,000 jobs for which accommodation has been removed.

Redirecting developers and planning authorities away from allocating social rented accommodation, in favour of units for sale within affordable housing schemes, shows that government is merely happy tinker around with tenure whilst wholly avoiding the key issue of insufficient supply. Seeking to compel local authorities to sell off ever more of their remaining housing to cover the costs of extending the Right to Buy, and its failed objective of expanding home ownership to housing association rental stock, is yet further evidence of a complete absence of policy formation focussed on the glaringly obvious – not enough new houses being provided where they are needed.

What lies at the heart of the problem of housing supply being so out of synch with demand? Clearly not the absence of land on which to build; only about 10% of UK land mass is under urban use (residential, employment, roads, urban green space and so forth). It’s the provision of land with planning permission that has consistently lagged demand for the past 30 years. People want to live where there are jobs and places to learn skills that will support them in the labour market, as well as good social and physical infrastructure.

But towns are surrounded by green belt, the relevance of which is rarely if ever objectively reviewed. Its ‘no go’ development status forces up land values on what is available to around £4.5m per hectare at the edge of London. And where permissions are obtained and banked at these high values and scarce allocations, there is an inevitable profit incentive for the volume house builders to restrict completions to maintain and maximise the sale price. This supply constraint is further aided by the enforced absence of local authorities as an alternative provider of new homes and the decimation of small builders by punitive bank lending conditions following the 2008/9 financial crash.

The received wisdom of green belt as an essential public asset and social good is largely mythical. The principal driver to its inviolate status is county paranoia of new towns and their migratory inner city overspill despoiling their vision of what benefits a relatively few economically blessed home-owning commuters and residents, coupled with fears of the wrong kind of neighbours and voters. The shire counties used the green belt to fix barriers around the post-war new towns that were forced upon them by government, and little has changed.

The political parties have consistently colluded in the green belt shibboleth for risk of upsetting what their advisors regard as the all-important Middle England voter. As put by Professor Ian Gordon, writing for the Centre for Cities, “Securing a decent quality of life, both for Londoners and their South East neighbours, will require region-wide efforts to re-model a much-valued – but outdated – green belt for the 21st century.”

So what is the quantum position today as a result of this history of political denial and supply side neglect? An annually sustained build rate around the 300,0003 mark is required for re-provision of expired stock and to address accrued under supply and future need. This order of new build necessitates a radical departure from the usual channels of parcel development and disjointed increments around and within existing settlements.

Daily Mail headline (May 2016)

Government must intervene at the policy and financial level to enable the release of green belt and delivery of a new generation of expanded towns. And as the wisdom of Ian Gordon points out again, politicians must look beyond their own boundaries: “isolationism is no longer sustainable given the threat posed by chronic housing shortages, as well as the size of the opportunities that an integrated regional approach to public investment would offer.” Politicians have also to stop pandering to home ownership fantasies and learn from the failed and costly assumptions on housing tenure, market forces, and the role of the public sector. Rents don’t have to spiral: Germany demonstrates stable, low and predictable rents because of the way the finance is sourced and structured. Social housing doesn’t have to be residualised and local authorities don’t have to be excluded from the supply side; indeed, we can see empirically how doing so has been a major contributor to the housing crisis.

However, in familiar fashion, the government’s latest piece of tinkering – this time through the Housing and Planning Bill – has only further removed local authorities. The bill sets the legal requirements for housing policy and will, according to Ministers, save the housing crisis – though in reality it is inadequate in generating enough dwellings as it does not have any radical mechanism for increasing the volume of supply. Only local authorities can do this. Local authorities need a requirement to build for the third of the population who will never be able to buy.

But following the third reading of the bill in the House of Lords, it became obvious that the minister for housing, Brandon Lewis, was unprepared to accept that local authorities have any productive role in negotiating the crisis. As it stands, Lord Kerslake’s observation that this Bill will be the death of social housing, has come true. Despite its clear view about demand and targets on housing, the government has purposely destroyed this potentially potent part of the supply side. In doing so, it has set out its stall against lower income families. However, it’s worth remembering, this is not unique to our current government: it was in fact perpetuated by 13 years of Labour rule.

“History will see this as the residential commodification era, in which housing provision seemed to lose all contact between supply and demand of housing as a utility and simply focused on supply and demand of investment – and that is worrying” (Peter Rees, Professor of Places and City Planning, UCL).

Green belt town Guildford ph. David Nichols

To get to an equilibrium is going to be challenging; overcoming ideological obsession with marginalizing the public sector and the entrenched myths of green belt alone will require brave voices and sustained commitment cross-party and across the development and planning sectors. As for our existing local authority housing estates, they can and should be renewed using the Complete Streets method that re-integrate estates into their local surroundings (see p. 33).

According to research by Savills4, this approach could yield an extra 73% in households on applicable land – from 78 homes per hectare currently to an average of 135 homes per hectare. Respect and engagement of the communities affected by the process is critical to ensuring success, but Savills indicates the potential is huge: “public and third sector landowners looking for sustainable income and long-term investors looking for popular and sustainable real estate would make Complete Streets the built form of choice.”

But above all, getting the capacity, skilled design and construction workers, trainers, facilities, and logistics in place after so many years of neglect will not be easy. Further delay and yet more tinkering is simply not an option.

Jeff Austin AoU is director of JVM Consultants

1. ‘Inside Housing’ from 2015, Nov: http://www.insidehousing.co.uk/revealed-40-of-ex-council-flats-now-rented-privately/7011266.article↩

2. 2015, Department for Work and Pensions↩

3. ‘Future Homes Commission report, Building the Homes and Communities Britain Needs’ https://www.architecture.com/Files/RIBATrust/FutureHomesCommissionLowRes.pdf↩

4. http://pdf.euro.savills.co.uk/uk/residential—other/completing-london-s-streets-080116.pdf

↩