David Green AoU, Global Practice Leader, Cities + Sites at Perkins+Will argues that planning of cities should be organised around the patterns and structures of streets and routes, the physical framework, rather than a prediction of land use.

Cities have always been designed, or planned, with consideration for the uses that would eventually come to inhabit them. As far back as Hippodamus’ plan for Miletus, one can see the intention in placing certain elements, or uses, within the city in specific areas. There was a place designated for the baths, for the theatre, for temples, and for many other places that were designated for specific uses. This remained true for the following 2,500 years, as exemplified in Penn’s plan for Philadelphia, Wren’s plan for London, and Oglethorpe’s plan for Savannah, for example.

This all changes in the late 19th and into the 20th century, culminating with the 1926 Euclid v Amber decision by the United States Supreme Court. This decision legalised, or at least rendered constitutional, the projection of uses as a valid method for planning cities, without regard for the underlying physical framework. Previously, the system of public rights of way had been the organising, unifying structure, and now it was to become the relative locations of amorphous blobs of use scattered throughout the landscape.

In planning for cities prior to this, the core element of the process was the creation of a physical, or dimensional, construct for the legal subdivision of land. Whether a series of blocks facing avenues, with frontages of a consistent 198 feet and cross streets of 99 foot widths, as in New York, or a series of square blocks, measuring 113 meters a side, chamfered at the corners, as in Barcelona’s Eixample, the physical construct of the city came first, and the use distribution, other than major public places, evolved as the city was populated. Use distribution was something to be managed, in the organic growth process, not something to project onto an undifferentiated plane.

It seems such a small thing but in the end, it had profound implications on the way we planned for the built environment, not just in the United States, but ultimately across the entire globe. The process of projecting development through the projection of future uses, land-use planning, came to permeate every aspect of city planning and directly replaced the street plan as the primary element of making cities. Unbelievably, it was a process of substituting the

most permanent element of the city for its least permanent element.

This legal transformation is, of course, running in parallel with the transformation of the modern ideology of the city, particularly with the work of Hilberseimer, Le Corbusier and others. The idea of separation of uses through buffers, etc., was adopted in the canon. It provided a legal as well as ideological foundation for the planning of cities in the 20th century.

This transformation in the way we understand the planning of cities changes the inhabitable, urban world from something that is adaptable and walkable to another world entirely, one that is static, difficult to change, and, for the most part, completely uninhabitable without a car. While this is true across every continent, except maybe Antarctica, it has had an inordinate effect on development in the Middle East, where new cities have usually sprung from nothing. This is particularly true because Middle Eastern cities were organised around a dendritic system of streets which was ill-suited to the new idea of land-use planning and supporting roadways that most western planners utilised. It was easier to remove the existing city instead of trying to incorporate it into its future growth. These circumstances can be described in two instances below. The first, how Kuwait City has transformed over the past 60 years, and the second, a more specific proposition for Doha.

In the first instance, we can look back to the historic fabric of Kuwait City, prior to the implementation of the 1952 masterplan. It was a moderately well-functioning city with uses distributed such that one could live and work in the city in the same way one might in Paris or London today. However, the charge for the 1952 plan was to ‘modernise’ Kuwait City. As such modern planning principles were instituted that rendered the existing fabric obsolete, something to be replaced with a much more efficient system. To do this, the 1952 plan recommended the complete demolition of the old town.

1951 Kuwait, 1952 Kuwait Masterplan, 2005 Kuwait Masterplan

Interestingly, the idea of interconnected spaces, a series of souks, for instance, was so strong in Kuwaiti culture that it wasn’t possible to fully eradicate the logic of the historic city, even in its complete reconstruction. We can see examples of this throughout the city; modern interpretations of the historic city fabric. There are many examples, but two stand out. The first is the relationship between the building, street and pedestrian in the work that was completed from the late 1950s through the early 1970s. The buildings were conceived of as background buildings whose primary purpose (whether intended or not) was to reinforce the space of the street, much in the same way the walls of the old city’s homes and markets created the streets of that era. In addition, each building was designed to provide covered arcaded walkways from property line to property line, which created a system of walkable, and critically, covered spaces that extended the public rights of way to include pedestrian activity. While modern urbanists were promoting open space in cities (re: 1961 City of New York Zoning Resolution), Kuwait, however, created a modern city that reconciled the idea of modern building and planning with the context of the desert environment. In 1968 one could easily live in Kuwait City with or without a shiny new car. It was possible to move through the city, a city in the desert, without a car, and with some level of comfort year round.

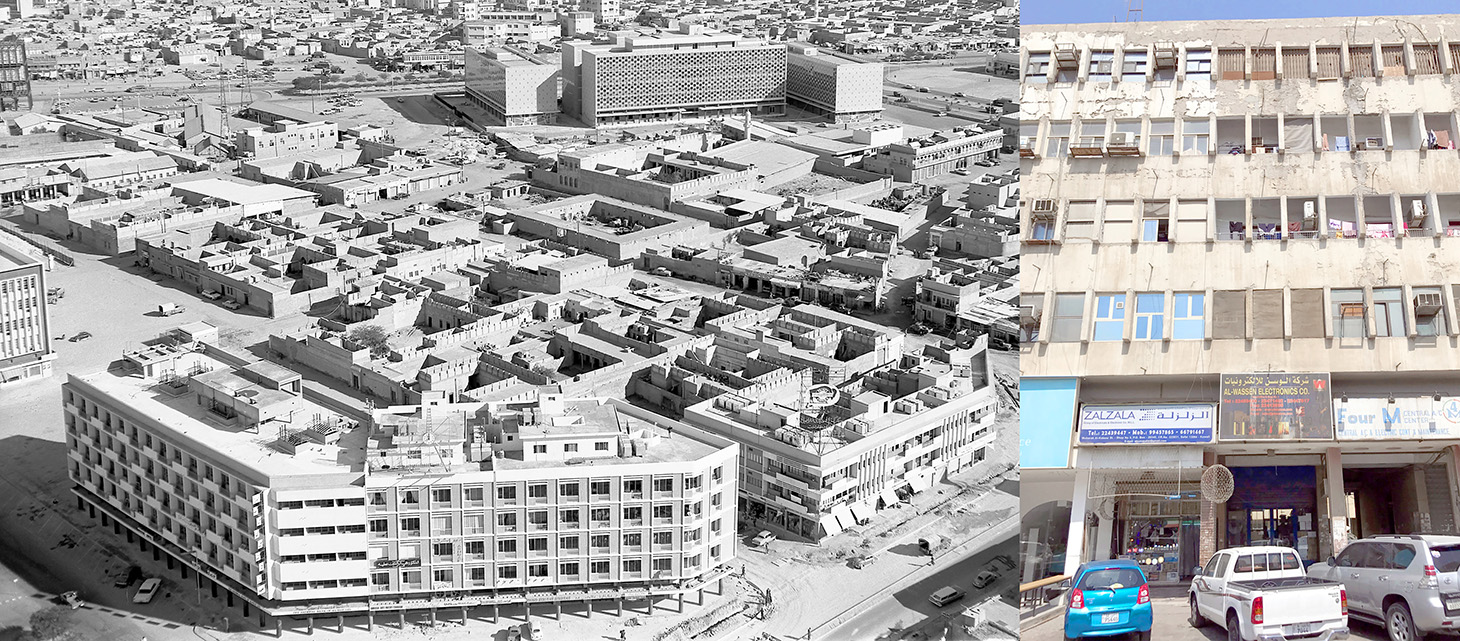

1960’s Aerial, 2017 Current Situation

This is further evidenced in the early development of the urban blocks in the city, still in evidence in the central Fabric Market, across from the historic souk. In this 1960’s era block, it is entirely possible to walk from building to building in shade (in some cases in air conditioned space, but mostly not). With the exception of crossing the arterial between the two areas, one can walk miles, along well populated, animated streets within the historic souk, the fabric market and beyond. The buildings look modern and are compositionally placed within the block, as objects in space, but in fact they form a highly connected network reflecting the logic of the historic souk.

Fabric Market Souk, Fabric Market Block

In both there is the absence of land use projections that require, or prescribe, certain building and urban typologies. Instead we see the primary operation as the projection of the ways (streets, alleys, souks) that connect and subsequently, to reinforce this apriori public framework, the design and construction of buildings, whether through connected, covered arcades (think Bologna in the desert) or through the creation of interconnected souks within the buildings themselves. The uses along these souks, and along the streets, are easily adapted. Each can accommodate multiple types of publicly accessible use at the ground level, and above can be institutional, commercial office, residential, etc.

Unfortunately for Kuwait City, the residual value of this has been systematically erased from the discussion about the future of the city and country. Today we see large towers, paeans to egomaniacal designers, almost completely disconnected from their surroundings, with large plazas, that may reinforce the ‘iconic’ tower upon which they sit, but does nothing for the urban fabric, fulfils none of its obligation to the collective, instead opting to exercise the rights of the individual in the creation of something, the city, that should be viewed primarily as a collective endeavor. This is being driven by the fact that parts of the city are simply projected as future uses, in isolation, and not as a systematic framework of rights of way.

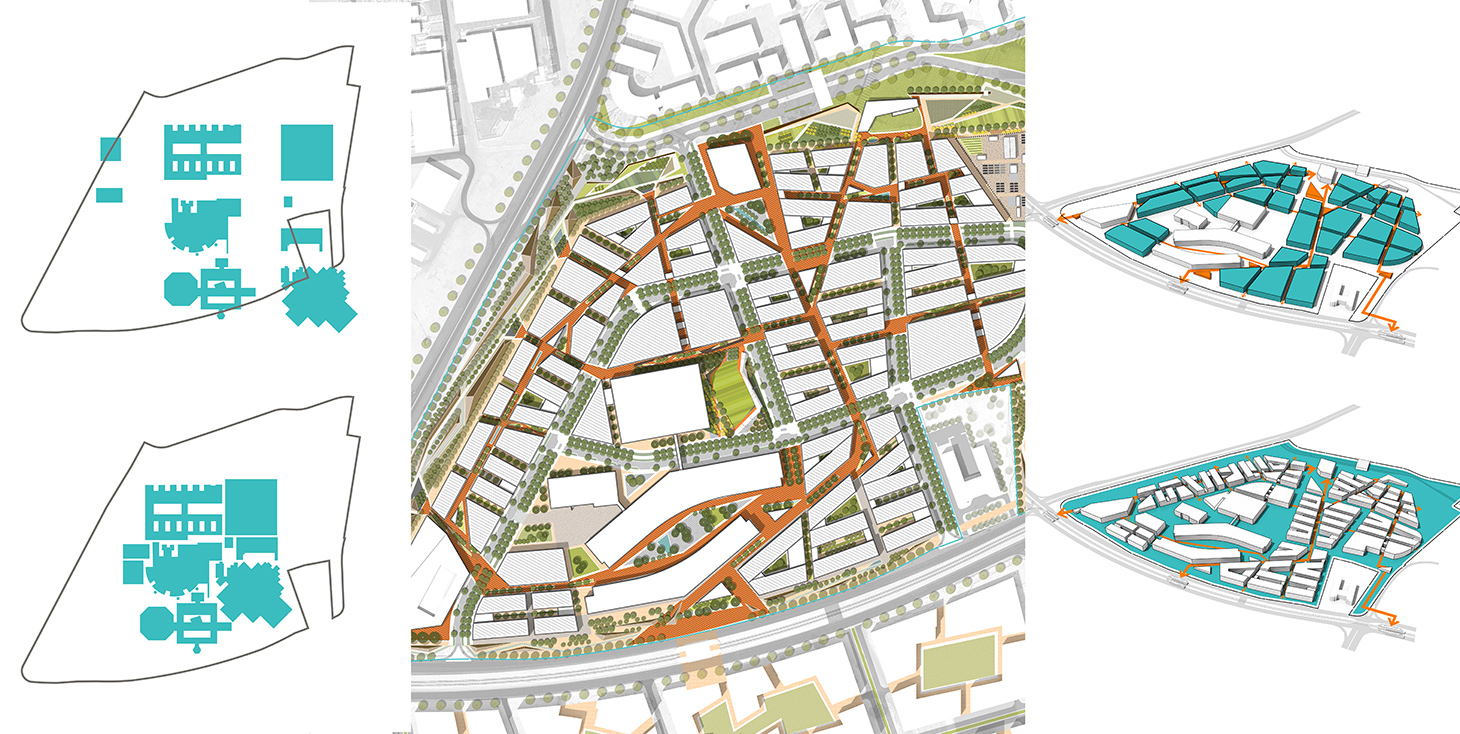

Compressing Doha, 2015 QRDC Masterplan, QRDC Streets and Souks

At this point, Kuwait is at a crossroads, and can protect the great examples of this convergence of modernism and regional context, as well as build this into planning for the future of the country, or it can continue to eradicate the cultural foundation upon which the country was built.

An example of how this might work is evidenced in the proposed master plan for the Qatar Research and Development Complex. This project was a mandate to populate a section of Education City with a specific use. In this case, it was research. However, instead of conceiving of this as a project, an undifferentiated plane upon which one could place buildings, it was conceived of as a series of streets and passages. The idea that there should be space between the buildings and that each building would be an iconic element, sitting in a privileged position, was discarded and replaced with the idea that the buildings would simply be the background for the public realm. The diagrams above demonstrate this simple idea.

In this scenario, much as with the Fabric Market in Kuwait, a double layered system of more conventional streets was incorporated alongside a system of pedestrian ways that were internal to the blocks. In this way it was possible to accommodate modern transport needs while addressing, and accounting for, the more basic needs of pedestrian circulation. In this case the streets are structured to promote pedestrian activity, as are the secondary pedestrian routes, with the intention of using the secondary ways as a tool for both creating connectivity, but also to reduce the size of the buildings’ footprints, which was a major concern for large, institutional buildings that were initially planned for the district. To support this, a very simple set of guidelines and regulations were put in place to ensure that the basic principles of the district were addressed in each of the coming projects.

In the end, this is a very simple idea, and one that we used to plan cities for millennia. We all walk down great streets, through tightly connected neighbourhoods or districts, and we enjoy the result, but somehow when we plan cities we revert to the projection and budgeting of land use and let the physical structure fall away, to be led by requirements for some future use that may or may not ever emerge. There is much more to learn from the patterns and structure of Kuwait City in 1952 than the suburbs of America, but somehow the discussion always devolves into the uses that are planned for an area, how much land is needed and how many cars must be accommodated. All of this is important, to be sure, but not more important than the physical disposition of the place we are making.

David Green AoU is global practice leader, Cities + Sites at Perkins+Will.