UN-Habitat predicts that by 2030 2bn people will be living in slums. Indeed this may be higher as it also predicts that by 2030 3bn people will need proper housing and access to basic infrastructure such as sanitation and clean drinking water. Urban anthropologist Line Algoed, who spent a month in the favela of Vila Cruzeiro in Rio de Janeiro before the 2014 World Cup, explains how community-led projects to upgrade slums have an important role to play in sustainable urbanism.

UN-Habitat predicts that by 2030 2bn people will be living in slums. Indeed this may be higher as it also predicts that by 2030 3bn people will need proper housing and access to basic infrastructure such as sanitation and clean drinking water. Urban anthropologist Line Algoed, who spent a month in the favela of Vila Cruzeiro in Rio de Janeiro before the 2014 World Cup, explains how community-led projects to upgrade slums have an important role to play in sustainable urbanism.

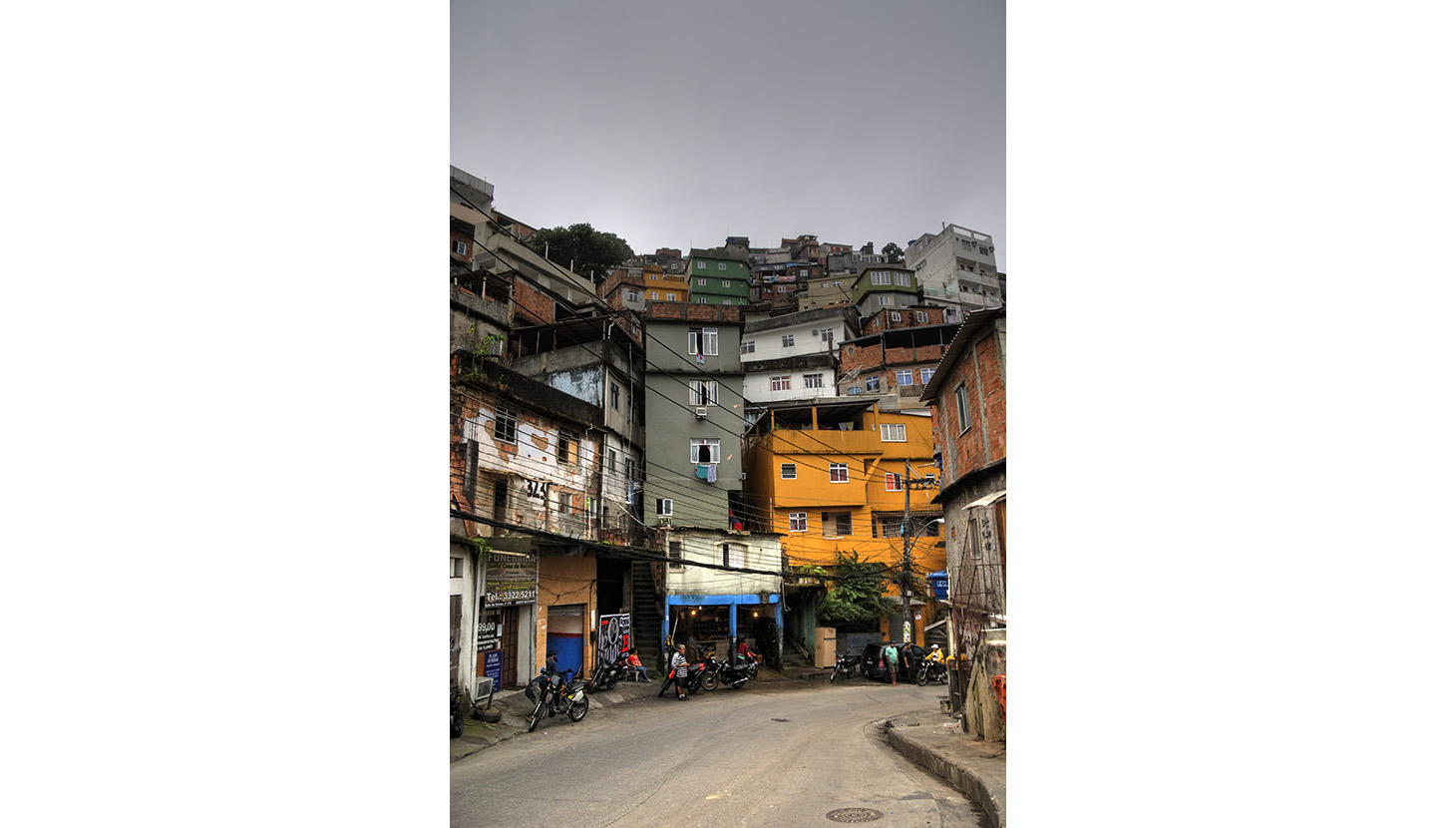

At a barbecue party on a rooftop looking out over an endless slum, my friend Angelo tells me he hopes Brazil is knocked out in the first round of the World Cup. A good result for Brazil, he says, will only distract people from what they are fighting for: social justice. Angelo lives in Vila Cruzeiro, one of roughly 1,000 favelas of Rio de Janeiro. With a break of just three years, which he spent with an English girlfriend in an Ipanema penthouse, Angelo has lived in this favela his entire life. He is an artist, exhibiting expressions of people’s frustration with the negligence of the state. Like millions of other favela residents, he has felt a combination of anger and frustration since Brazil was chosen as the host of both the World Cup and the Olympics, two major sports events only two years apart. “Suddenly, we seemed to have the billions of dollars hidden somewhere,” he says, “whereas we have always been told there is no money to do anything about the precarious situation we are in.”

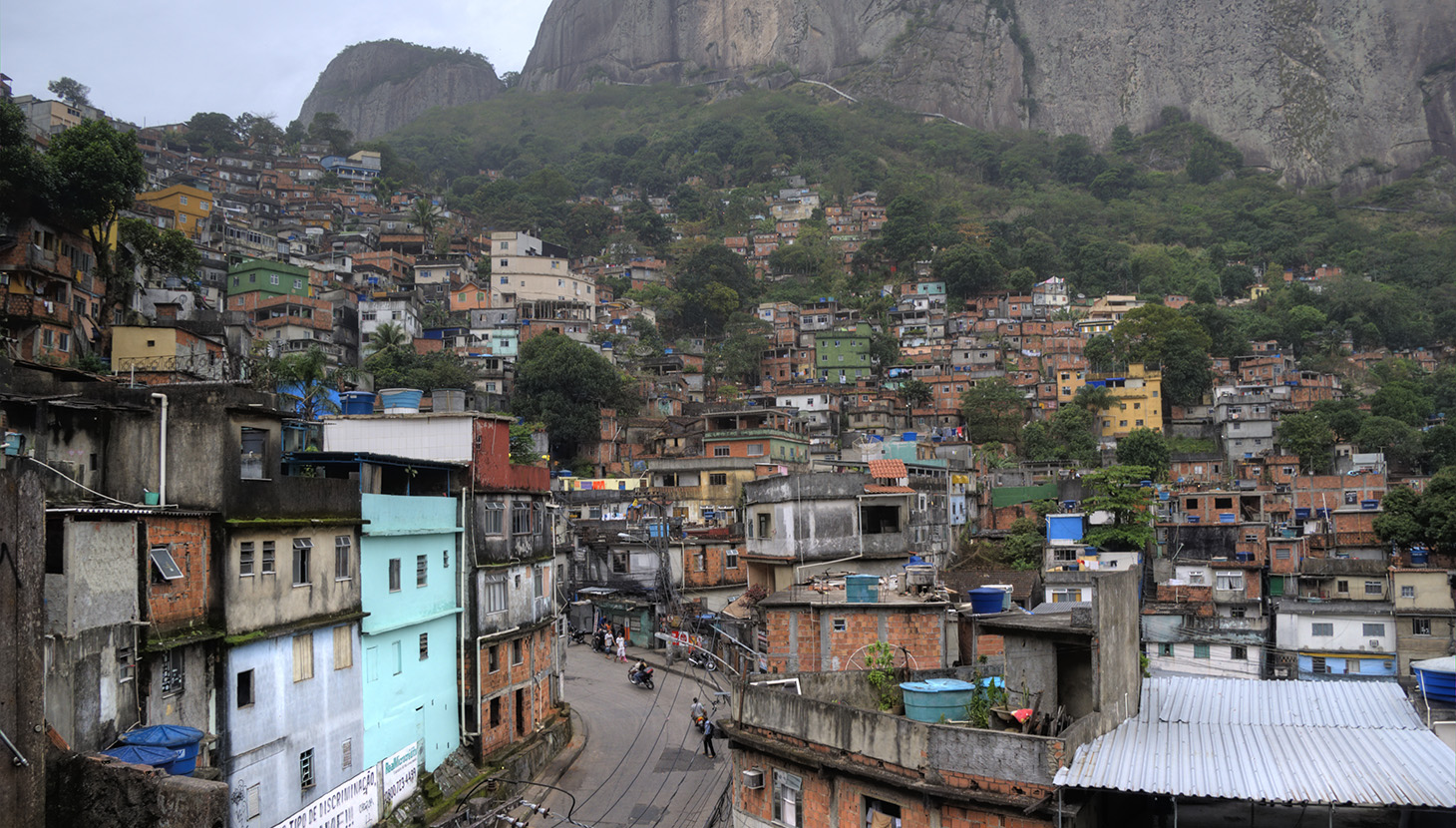

The ‘us’ he refers to is him and roughly 1.4 million other people living in favelas in Rio de Janeiro, or a total of almost 12 million in Brazil and a billion worldwide. In mega cities like São Paulo or Rio de Janeiro, the formal housing market today supplies to only 20% of the housing demand. Consequently, it is predicted that the number of slum dwellers worldwide will double, reaching 2 billion by 2030. Slum dwellers will by then represent one-fourth of the total global population.

The unabated growth of slums is not attributable to the pull of cities and the supply of jobs in urban centres. As Mike Davis argues in the influential Planet of Slums (2006), they grow because people are pushed out of rural areas, due to chronic under-investment in areas outside of cities. The state tends to serve the interest of the propertied classes, who are mainly concentrated in cities. Urban poverty is rapidly becoming one of the most significant and politically explosive problems of the 21st century, which is why working with slums should be on the agenda of those of us who are interested and professionally involved in sustainable urbanism.

State interventions in slums in the past have been dominated by the view that favela residents are better off when relocated to state-owned high-rise public housing. However, many of the dwellers in these relocation projects either quickly leave their new-build home or see their personal safety deteriorate due to the loss of community and detachment from social protection systems. When planning and constructing such housing projects, often in peripheral areas of cities, strategies for developing the livelihood of slum dwellers are largely ignored. Housing is not only about shelter, it’s as much about work. Like everywhere else, the economic strategies employed by slum dwellers are intrinsically linked to where they build their housing. A first step in successfully planning sustainability in cities is to try to unravel these practices and then work with communities to enhance what they have already started.

On a first walk around Vila Cruzeiro, I was struck by the fact that the quality of the homes is not at all that bad. Many favela dwellings do not look like the images portrayed by the media: inadequate sheds built out of recycled construction waste. The majority of people’s income is invested in their houses, and the improvement of the houses is a lifelong project spanning several generations. The many corner shops selling building materials indicate the importance of construction for the local economy, and manifest favelas as places of production that serve the entire city.

The productivity and entrepreneurialism in these places is striking for someone coming from outside a favela. Spaces for work are set up in garages and on the streets, people transport materials in and out of home workshops. Streets and public squares are used for a combination of work and play. As noted in the influential 2003 UN report The Challenge of Slums, slums are in many ways the wheels that keep the city turning, as the place of residence for low- income employees.

“Slums, as the first stopping point for immigrants, provide the only affordable housing that will enable immigrants’ eventual absorption into urban society. The mixing of different cultures and people looking for opportunities frequently results in new forms of artistic expression, cultural movements and levels of solidarity largely unknown in other areas of the city. Slum dwellers have developed economically rational and innovative shelter solutions for themselves.”

On that account, favelas are primary examples of community-led urbanism and social resilience. Clearly, the state is incapable of providing for the lowest-income communities, therefore they take matters into their own hands. The practices that underpin social resilience are prodigious and deserve attention from urban and economic planners in particular.

It is thus time to move away from the deep-rooted stereotypes of slums and their dwellers, and start to activate and invest in the talent that exists in these places. Rather than developing expensive and ineffective new-build housing projects, planners should focus on grassroots upgrading projects, driven by the needs and capacities of local residents, to enhance the existing fabric of favelas. At the same time they could play a role facilitating broad stakeholder participation in upgrading projects, which is a key requisite for sustainable outcomes in urban planning.

An example of such a project is Favela Painting, driven by local residents and instigated by the Dutch architects/artists Jeroen Koolhaas and Dre Urhahn. Bringing together large groups of local residents, the collective transforms façades of favela homes into large unified art works. Alongside training and employment opportunities, local residents create a colourful platform to show the world that their communities are not just places of poverty and violence. Together they have established a gateway that draws people in with an interest to invest in the talent and social energy of favelas.

Recreating the work we do in the UK, Cospa intends to take the idea of Favela Painting a step further, by enabling favela residents to renovate the interior of their homes. Local professional builders train young favela residents, who gain vocational qualifications in construction and building skills, offered by a recognised Brazilian training institution. The project is enabled and supported by the construction industry, with companies who see the benefit of investing in the talent of future employees and clientele, by donating materials and offering work placements and apprenticeships. The aim is to pilot a new approach to developing skills and vocational training in slums, and invest in a resident-led model for the upgrading of existing housing stock.

These projects do not pretend to provide the whole solution for the enormous challenges facing cities. But they do provide a model for public and private sector organisations to take responsibility and help slums dwellers improve their own neighbourhoods and economic opportunities. Which is what they have been doing for decades.

Line Algoed is a Young Urbanist and urban anthropologist who seeks ways to link community initiatives with urban policy. She is an Account Director at Cospa, a London-based social innovation agency, where she manages the VIY project, enabling young people to organise their own youth clubs whilst gaining vocational qualifications in building and construction skills guided by local tradespeople. Currently, she is working to set up a Cospa project in Rio de Janeiro in collaboration with Favela Painting. This article is about the role of community-led slum upgrading projects in sustainable urbanism. It’s also a plea for the use of anthropology in urban planning.