The physical and personal elements of cities are difficult to predict let alone design for. Yet this combination is what marks Milton Keynes out as different to many of its contemporaries – the passion behind a vision which put social structures on equal billing with the physical. Dr Noël James AoU, director of the Milton Keynes City Discovery Centre, explains the effect this had on our most famous new town.

Animals we are, and by nature we are designed to design: habitats to make the most of inclement weather; intricate cellular housing, innovative architectural conceit. I could be talking about Solar World; I could be talking about Energy World, I could be talking about the early days of Milton Keynes. But I am not. I am talking about beavers; leafcutter ants; wasps. I am talking about nature by design and design by nature. And in so doing I am talking about masterplanning on a grand and frightening scale, and I am also talking about its implicit counterpart – complex and well-developed natural social structure, without which these grand designs of nature could not serve their makers.

And so, actually, I am talking about Milton Keynes. The very early days when the social infrastructure was seen, rightfully, to be as important as the physical. Without which, the physical, however innovative, would become and remain sterile, soulless, and disconnected. Isolation. To a degree, something the intervening years between the disbandment of the Development Corporation and the more recent development of the Eastern and Western Expansion Areas have shown in private developments that did not consider that housing needs to be for people, not plans, and that people need emotional infrastructure as much as they need grid roads that get from A to B in the shortest space of time.

But this think piece is not criticism of Milton Keynes – far from it – it is a paean to those early masters of forethought in both the physical and the personal.

50 years ago:

The new city must be a place for people. We must try to offer them an environment as conducive as possible to good health, happiness, stimulation and satisfaction during their youth and working lives and contentment and care in their old age

(Lord Campbell, Milton Keynes Development Corporation, 1967).

49 years ago:

At the earliest stage of its task to prepare the proposals of the new city, the Corporation established its intentions to consider the social aspects of the [Master] Plan as fully as the physical

(The Plan for Milton Keynes, 1970).

Speak to any of the pioneers from those first decades of Milton Keynes and you will find people who believe passionately in the ethos, the community, and the vision of the town they chose as their own.

The passion comes from many things: a shared experience; the wonder of having one’s own home, garden, space; being part of a new metropolis rising from the (agricultural) ground, and the time literally spent living on a building site; and the sense of fostered and developed community – a sense of social cohesion that was planned as carefully as the initial beauty of Netherfield emerging from a geoscape reminiscent of the prairie and its sky (for which see some of John Donat’s startling early images).

A sense of cohesion and ownership that spread throughout the new town from day one. It was always there. It was always intended to be there. But now let’s return to the physical infrastructure; let’s return to the grid.

The city of roundabouts. 70 miles an hour. Grid roads. Horizontal and vertical axes, so you never get lost. H4, V7. You never need to know the street name to get where you’re going. But you do know the street name, anyway. You know Your Town like the back of your hand. You know it like a map, like a plan.

The grid roads are a vital and integral part of the overall infrastructure. They are built into the geomorphology; the roads follow the gentle undulations of the landscape and are sympathetic to its shape. Estates old and new nestle within them. And these grid roads are vital also to the social infrastructure. Then, they grew communities. Now, in many cases, they keep them apart.

Those 1km square grids were intended to provide many centres within the town – they would contain houses, a pub, a community house, a school, shops, employment, facilities, leisure. They would house communities. And all over the town this network of communities would make up the cohesive whole, as important to identity and well-being as a place made well. Indeed, a series of discrete communities that made a place.

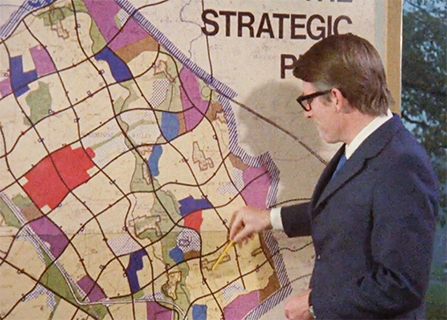

Fred Roche, general Manager MKDC explains the grid system on film © BFI

This image of early central Milton Keynes is the masterplan made life – its sparsity, its promise, its newness, its potential – this drew people – this excited people, this was a chance to build one’s life again from scratch. This was the psychological made actual; the hopes and dreams made real.

People moved to Milton Keynes in the early 70s because they needed a place. They left families and networks behind them and started afresh, anew, and away from everything they knew. But they were not alone. The Development Corporation had not only the foresight to design a town made up of urban villages but also to provide community workers, arrivals visitors and a support network that made people welcome and turned a house into a home and a town into the pride of the people. In fact, the plan outlined that efforts would be ‘directed onwards encouraging residents to the city to create their own community life and … requires that opportunities to do so are brought to the notice of the residents.’

And so what? Isn’t this obvious? Shouldn’t all town planning incorporate such vision? Yes; it should. But it doesn’t. And in the intervening years without the drive of this vision the grid squares have to some degree instead created ghettos and isolation and social deprivation and decayed estates where once there was excellence and enthusiasm.

And so what? Now we realise that this blueprint from the past, not without its mistakes, was in fact a vision of social and physical excellence – truly a vision of utopia, a type of almost-garden city ethos that we have forgotten and now are trying desperately, without the necessary resources, to remember.

Central Milton Keynes © Living Archive

The recent House of Commons briefing paper 06867 (July 2017), ‘Garden Cities, Towns and Villages’ posits in some part that a return to garden city-type planning ‘remains an attractive option to meet this [housing] shortfall,’ and while it mentions briefly that some social infrastructure should be in place there is rather more focus on the skepticism of organisations such as CPRE that ‘without a definition of what constitutes a garden city, town, or village we will have to accept them as “anonymous, soulless, land-hungry housing estates.”’ (Briefing Paper p. 18, n. 56)

But why accept this? Why not learn the lessons of the past – and not just the poor ones, but the rich ones. Return to the new town drawing board and define what makes a community. There is no shame in returning to what worked in the past. Not everything we have left behind us was a mistake.

It is time to remember – the tariff now levied on developers certainly has been shown to make a difference in the expansion areas where community mobilisers are once again at work – but it may not be enough. Let us keep asking the question before we again forget – if it is in our nature to design, if, as animals, we design to survive, then why, repeatedly, do we forget the human element within our design? Why do we not include the social masterplan as an equal and integral component of the physical? Houses should be for people, and it is people who make our towns. And if we forget to plan for that then we plan instead for dystopia. Haven’t we had enough of that?

Dr Nöel James AoU is director and CEO of the Milton Keynes City Discovery Centre